The heavyweight king of the Comics

Story by Kirk Lang

In the first half of the 20th Century, when the Golden Age of Boxing coincided with the Golden Age of Comics, there arose an unlikely American hero – Joe Palooka.

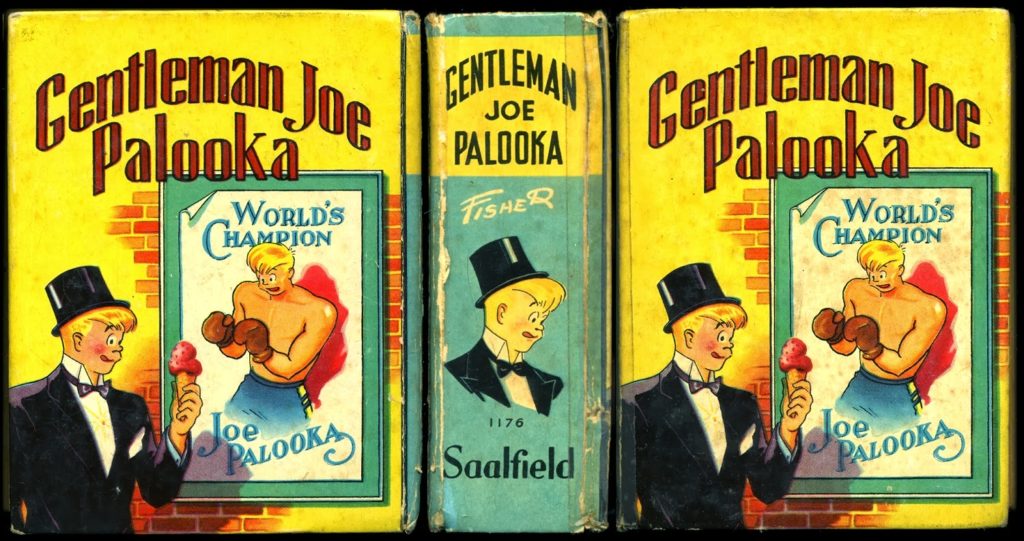

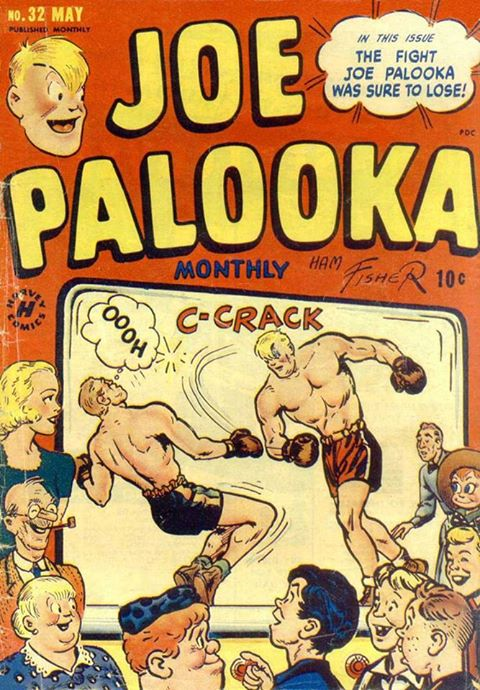

The lead character of a comic strip created by Hammond Edward ‘Ham” Fisher, Joe Palooka was anything but a palooka, a term used to describe a fighter of lower-tier skill. The strong-jawed Palooka was, in fact, the heavyweight champion of the world and would later become a war hero who fought everyone from Nazi soldiers to underwater sea creatures. Joe Palooka did not have the highest IQ in the world, but what he lacked in education, he more than made up for in being a stand-up human being.

According to HistoryNet.com, “Readers found Joe’s “common-man” persona appealing. He was unpretentious and had a strong work ethic. He possessed integrity, along with small town simplicity and morals.” He also did not drink or smoke and was good to his mother.

Fisher, who hailed from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, held a myriad of jobs before finding success with Palooka. A truck driver, a brush peddler, ad salesman and occasional reporter, to name a few, Fisher was inspired to create Joe Palooka after meeting real-life prizefighter Pete Latzo in 1921 outside a poolroom. Latzo was sort of the 1920’s version of Chuck Wepner, in that he inspired a far more famous character than himself. Wepner, best known for a losing effort to Muhammad Ali in 1975, was the inspiration for “Rocky Balboa.” A young Sylvester Stallone, watching the fight at a Los Angeles theater, was so impressed with the underdog, known as “The Bayonne Bleeder,” that he subsequently wrote the “Rocky” script, which led to a 7-film series that earned millions at the box office.

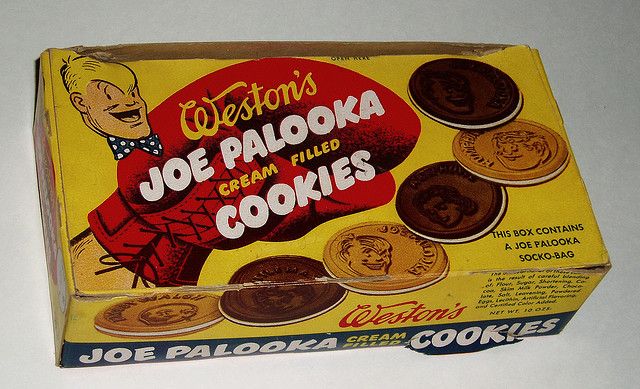

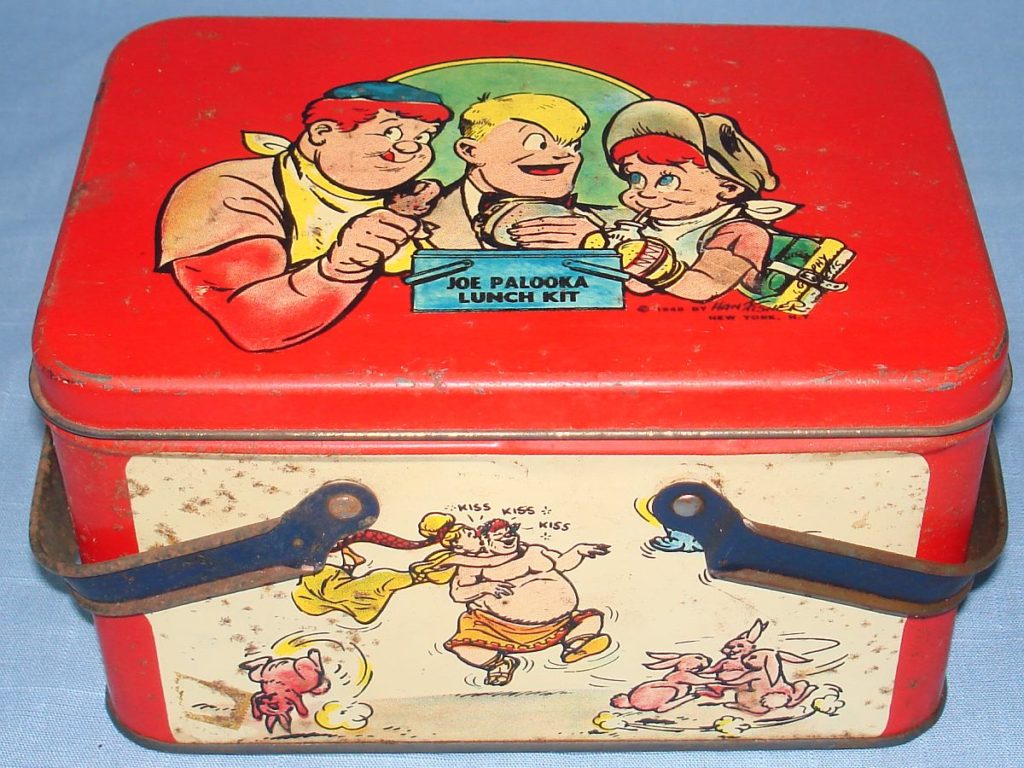

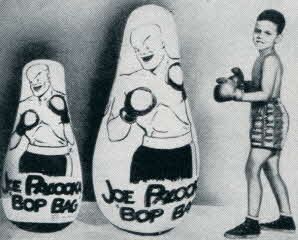

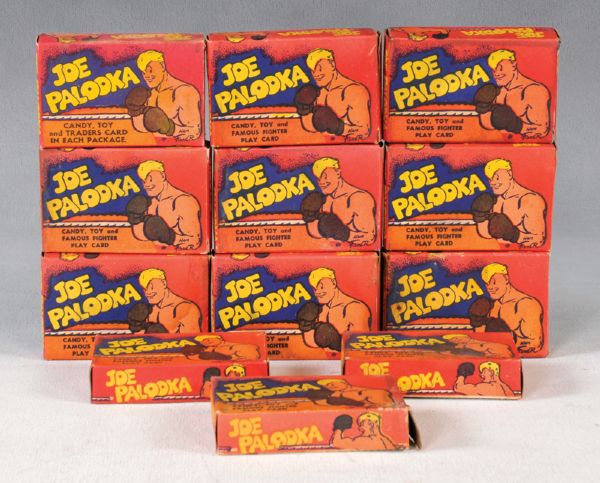

Latzo, whose reign as the World’s Welterweight champion lasted less than 12 months – he won the title five years after meeting Fisher – retired with a modest record of 63-28-3 (25 knockouts), and lost his final 12 listed fights. Pete, however, could take pride in the fact he helped launch a beloved comic strip and comic book character that was brought to life on radio, television and the silver screen, and whose image appeared on countless pieces of candy and merchandise (everything from lunch boxes to air pumps) during the height of Joe Palooka’s fame.

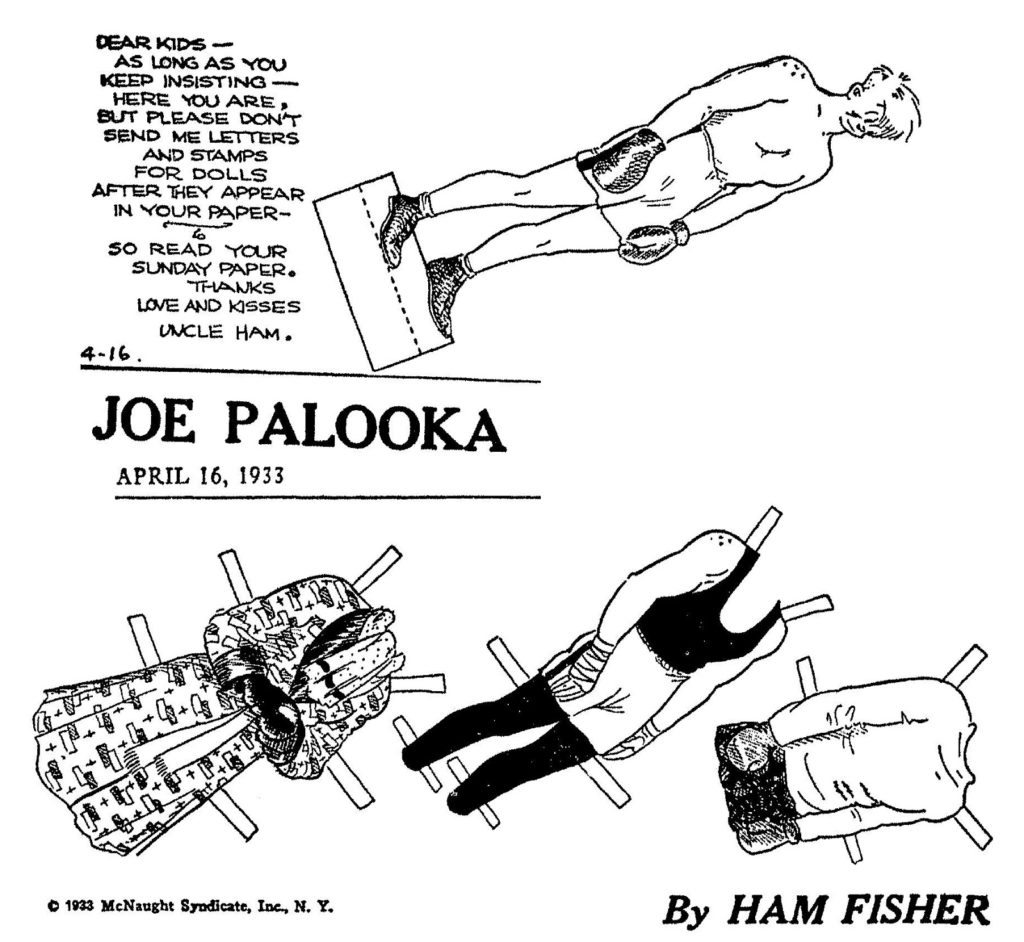

Success, though, was not immediate after meeting Latzo. Far from it. Nine years passed between meeting Latzo and Joe Palooka’s comic strip debut, due in part to tinkering with the character and also multiple rejections from newspaper companies, including Captain Patterson’s New York Daily News, where Fisher had been employed.

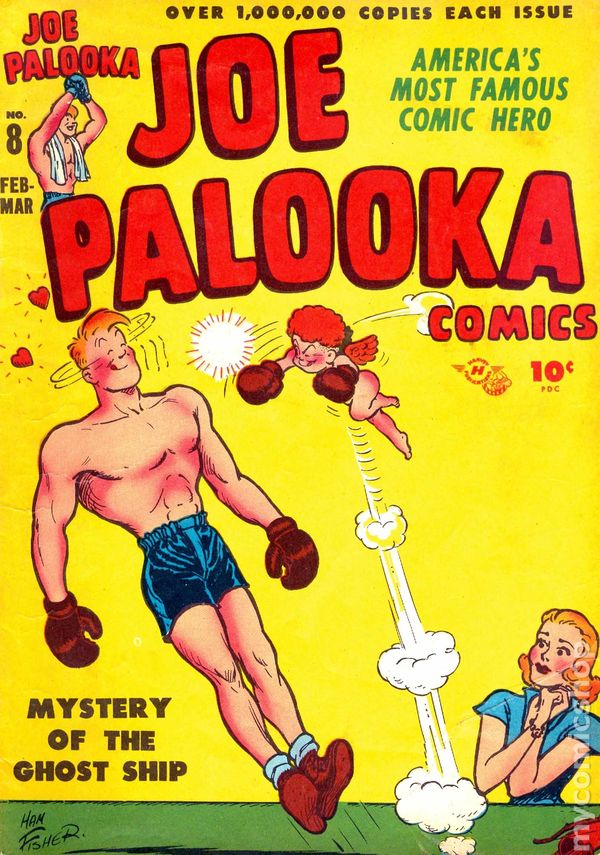

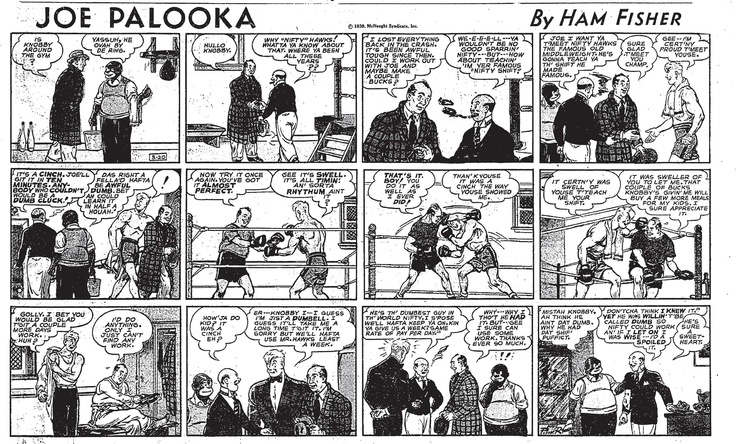

Fisher had initially thought of naming the character Joe Dumbelletski or Joe Dumbbell. Fisher finally sold Joe Palooka in 1929, when, while trying to pitch Dixie Dugan to newspaper editors, he was allowed by the McNaught Syndicate to pitch his own strip. He managed to convince nearly two dozen newspapers to carry Joe Palooka. The strip made its debut on April 19, 1930. Palooka’s image, in the early going, allegedly saw his appearance change to sort of mimic whoever was the reigning heavyweight champion. However, Palooka’s image eventually settled into a “cowlicked blonde” during the time of Joe Louis’ championship years. America would not have been ready in the 1930’s to see its comic strip boxing hero switch ethnicities.

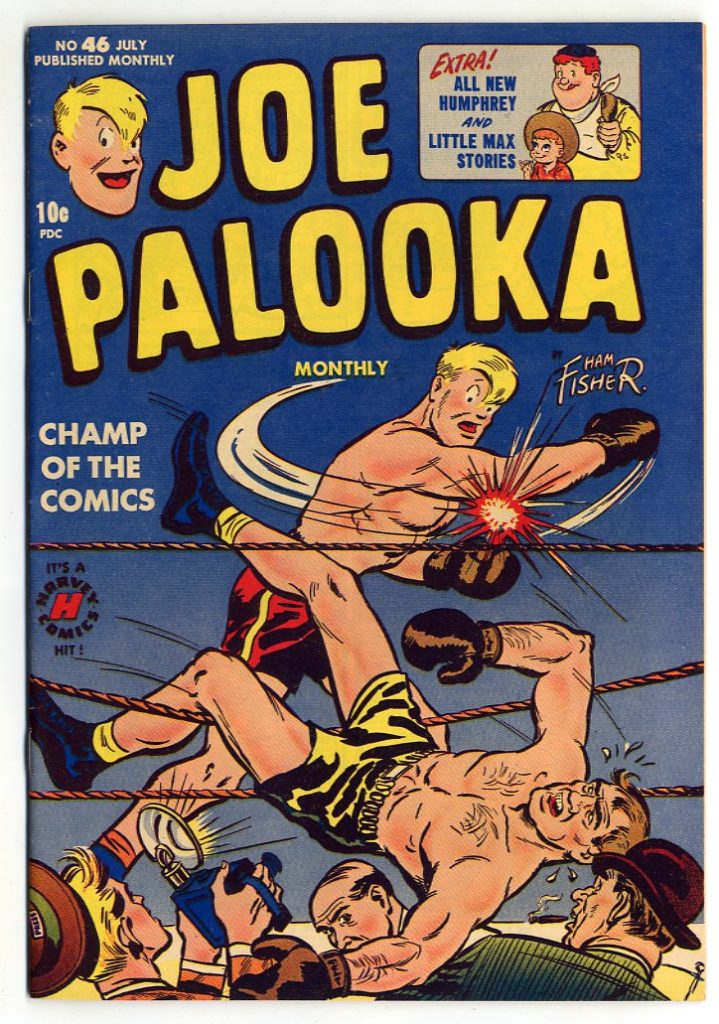

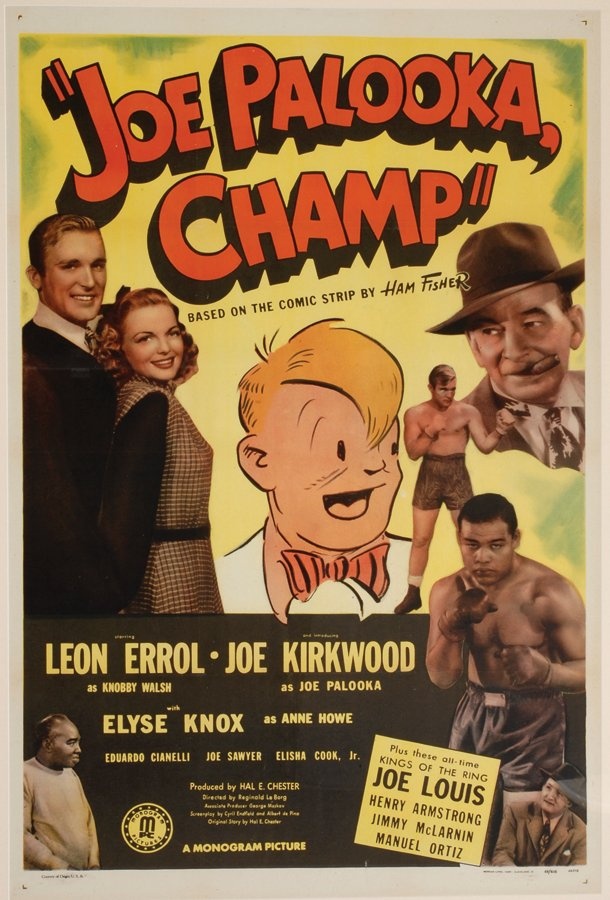

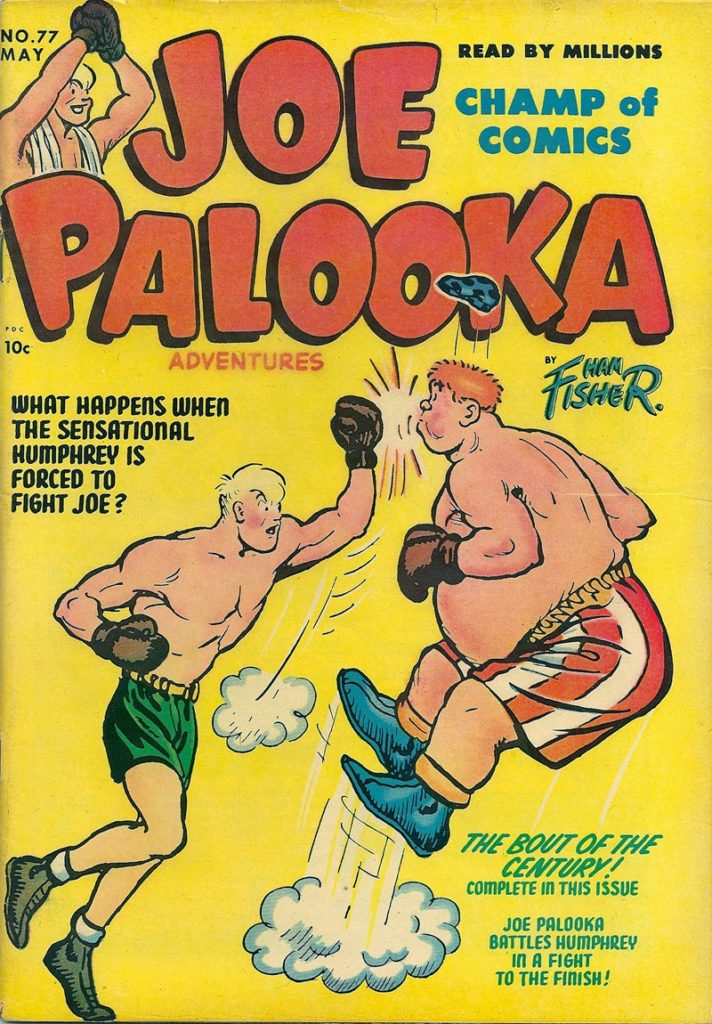

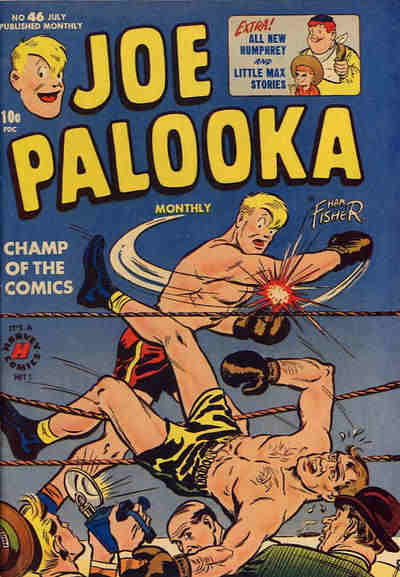

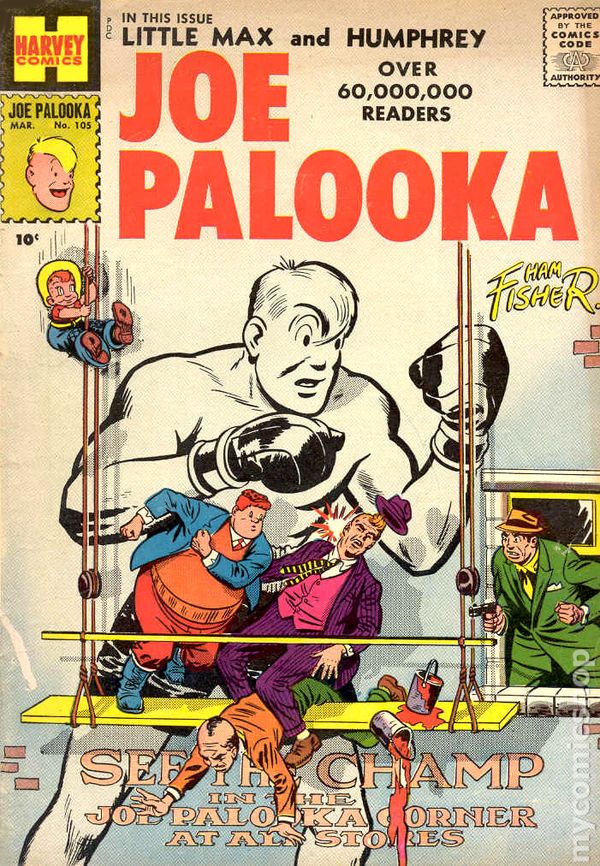

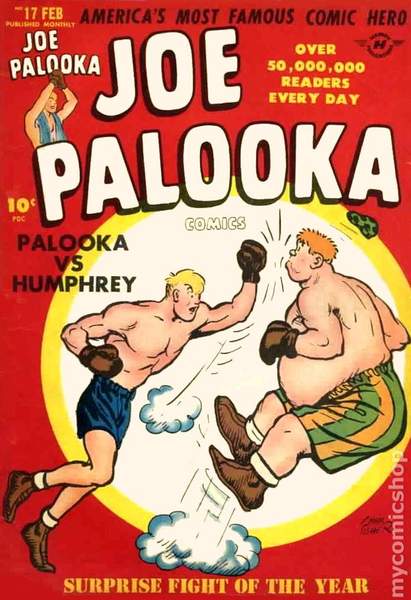

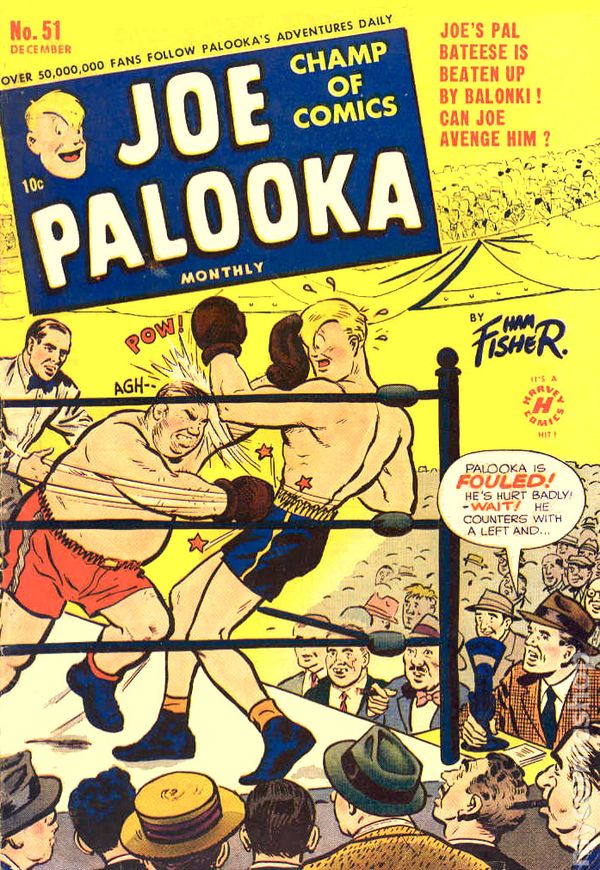

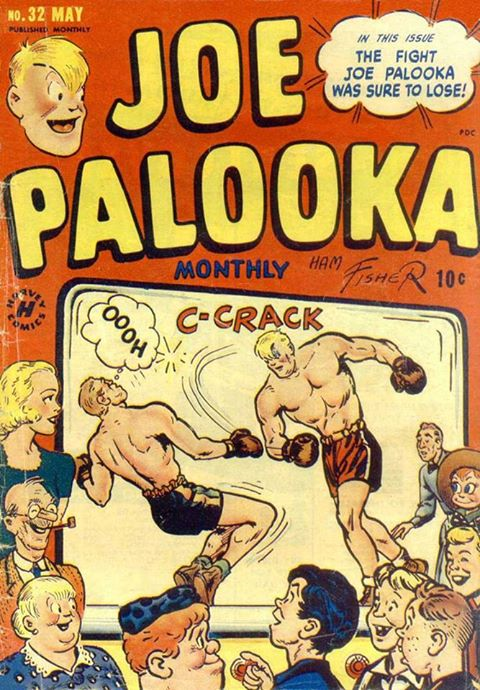

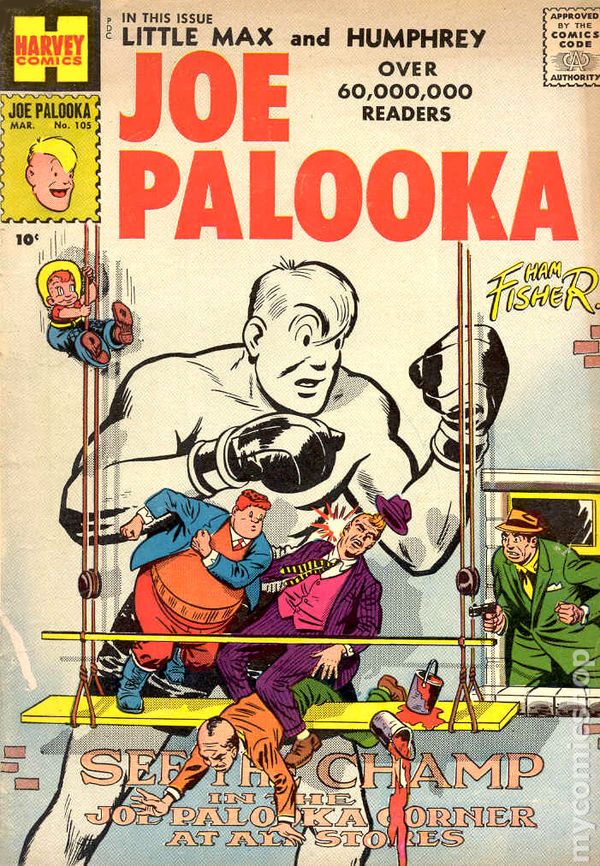

Joe Palooka’s comic strip was supported by a cast of characters that included Knobby Walsh, Joe’s manager; girlfriend and future wife Ann Howe; Joe’s mute orphan sidekick Little Max; Smokey, Joe’s African-American valet who later becomes a sparring partner and good friend; and lovable giant Humprey Pennyworth, a smiling 500-pound blacksmith who wielded a 100-pound maul. Joe Palooka proved so popular that Little Max and Humphrey Pennyworth subsequently had their own comic books. When Joe married Howe in print on June 24, 1949, the strip was carried in 665 American newspapers. In addition, 125 foreign papers also carried the strip.

Joe Palooka’s comic strip was supported by a cast of characters that included Knobby Walsh, Joe’s manager; girlfriend and future wife Ann Howe; Joe’s mute orphan sidekick Little Max; Smokey, Joe’s African-American valet who later becomes a sparring partner and good friend; and lovable giant Humprey Pennyworth, a smiling 500-pound blacksmith who wielded a 100-pound maul. Joe Palooka proved so popular that Little Max and Humphrey Pennyworth subsequently had their own comic books. When Joe married Howe in print on June 24, 1949, the strip was carried in 665 American newspapers. In addition, 125 foreign papers also carried the strip.

Al Capp, who would later gain fame for the comic strip Li’l Abner, was Fisher’s first assistant on Joe Palooka. However, the two parted ways fairly early on. When the Fisher and Capp partnership dissolved, Fisher hired three assistants, including Moe Leff, who later drew the strip for four years after Fisher committed suicide in 1955. Cartoonist Tony DiPreta then took over as the successor artist for Joe Palooka in 1959, his artwork complementing Morris Weiss’ scripts. DiPreta remained on board for Joe Palooka until its comic strip end in 1984.

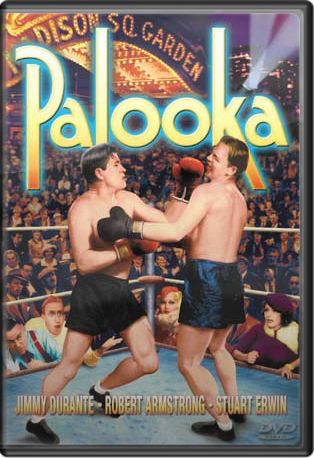

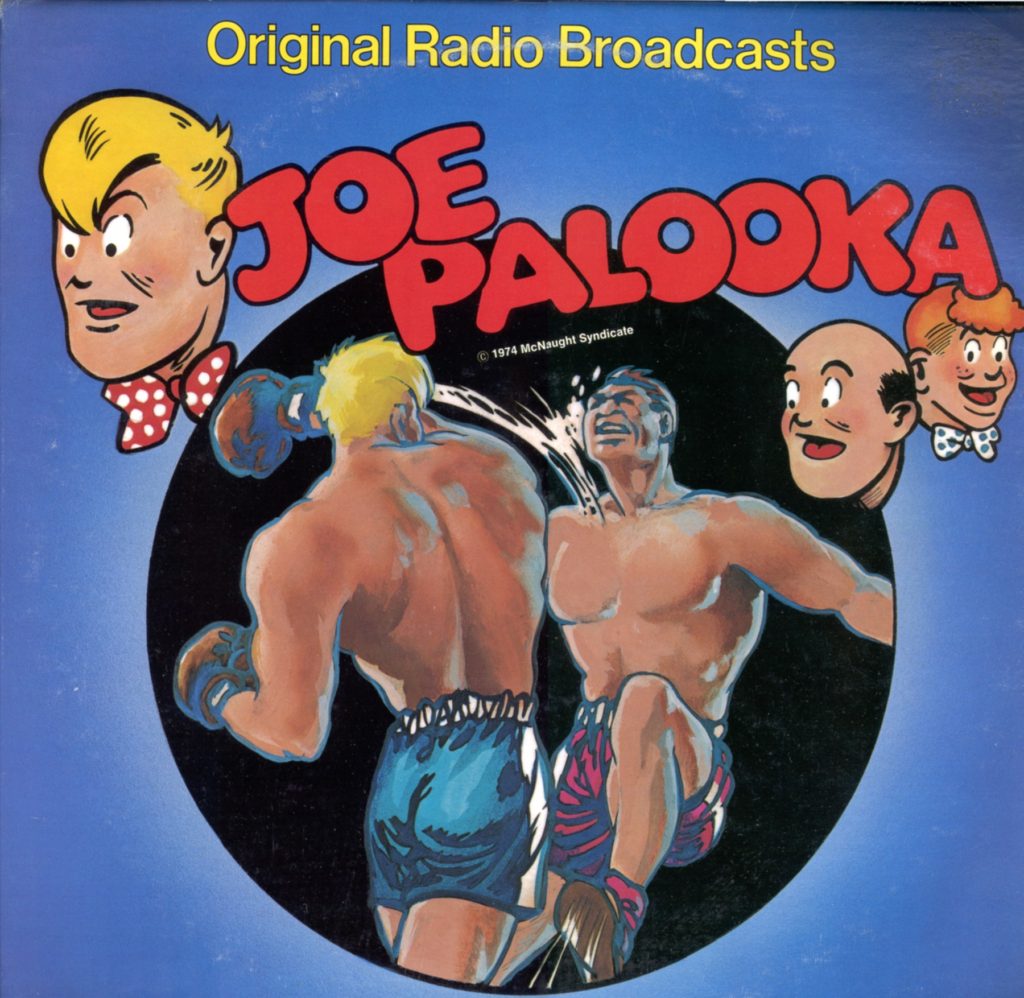

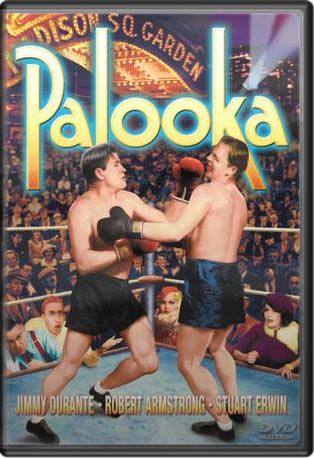

The comic strip Joe Palooka was only two years old in 1932 when it spawned a radio series of 15-minute sketches. The Story of Joe Palooka aired over CBS affiliate stations between April and August of ’32. Two years later, the stand-up character made his movie debut in the film simply titled Palooka. Future Academy Award nominee Stu Erwin acted in the title role while Jimmy Durante portrayed Knobby Walsh, Joe’s manager. According to the movie’s description, Knobby discovers Joe and trains him to fight and beat the reigning drunken champion, Al McSwatt, who was portrayed by James Cagney’s brother William.

The comic strip Joe Palooka was only two years old in 1932 when it spawned a radio series of 15-minute sketches. The Story of Joe Palooka aired over CBS affiliate stations between April and August of ’32. Two years later, the stand-up character made his movie debut in the film simply titled Palooka. Future Academy Award nominee Stu Erwin acted in the title role while Jimmy Durante portrayed Knobby Walsh, Joe’s manager. According to the movie’s description, Knobby discovers Joe and trains him to fight and beat the reigning drunken champion, Al McSwatt, who was portrayed by James Cagney’s brother William.

The film was well-received and it was followed by a series of nine two-reel Vitaphone shorts starring Robert Norton as Joe and Shemp Howard, to later become one of The Three Stooges, as Knobby. His comedic skills shone brightly in the role. The shorts aired between 1936 and 1937. The titles were as follows: For the Love of Pete, Here’s Howe, Punch and Beauty, The Choke’s On You, The Blonde Bomber, Kick Me Again, Taking the Count, Thirst Aid, and Calling All Kids.

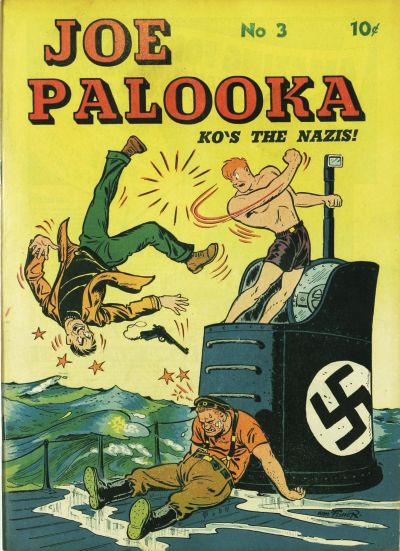

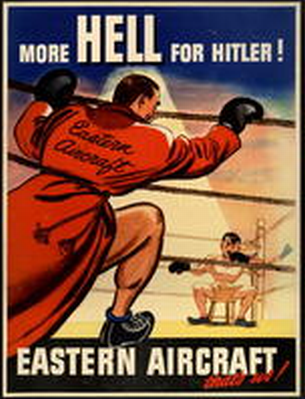

Joe Palooka also has been credited in helping to sell World War II era Series E bonds to the public as a wartime financing initiative. In a strip that was published in 1940, Joe decides to enlist in the Army, pre-empting what many young Americans did when the Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. When Joe tells Knobby he’s going to enlist, Knobby responds, “If they want ya, they’ll draft ya. Ya got plenty of time for that. You registered.”

Palooka shot back, “I know. But I’m goin’ anyway.” While others in various comic strips would enlist and fight in the war, Joe Palooka is on record as having been the first to do so.

Joe Palooka returned to the silver screen in 1946 when Monogram Pictures bankrolled a series of 11 low-budget films starring Joe Kirkwood, Jr. as Joe. It could be said these films – and Joe Palooka’s popularity with the general public – did much to earn Kirkwood a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Of 16 acting credits, 12 are Joe Palooka-related, including the TV series The Joe Palooka Story. Kirkwood reprised his role as the boxer for 26 episodes that aired between 1954 and 1955. Former light heavyweight champion Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom had a role in the show, playing Humphrey Pennyworth.

to the silver screen in 1946 when Monogram Pictures bankrolled a series of 11 low-budget films starring Joe Kirkwood, Jr. as Joe. It could be said these films – and Joe Palooka’s popularity with the general public – did much to earn Kirkwood a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Of 16 acting credits, 12 are Joe Palooka-related, including the TV series The Joe Palooka Story. Kirkwood reprised his role as the boxer for 26 episodes that aired between 1954 and 1955. Former light heavyweight champion Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom had a role in the show, playing Humphrey Pennyworth.

Fisher’s comic strip often communicated patriotic messages and during wartime he even had Joe speak out against racism.

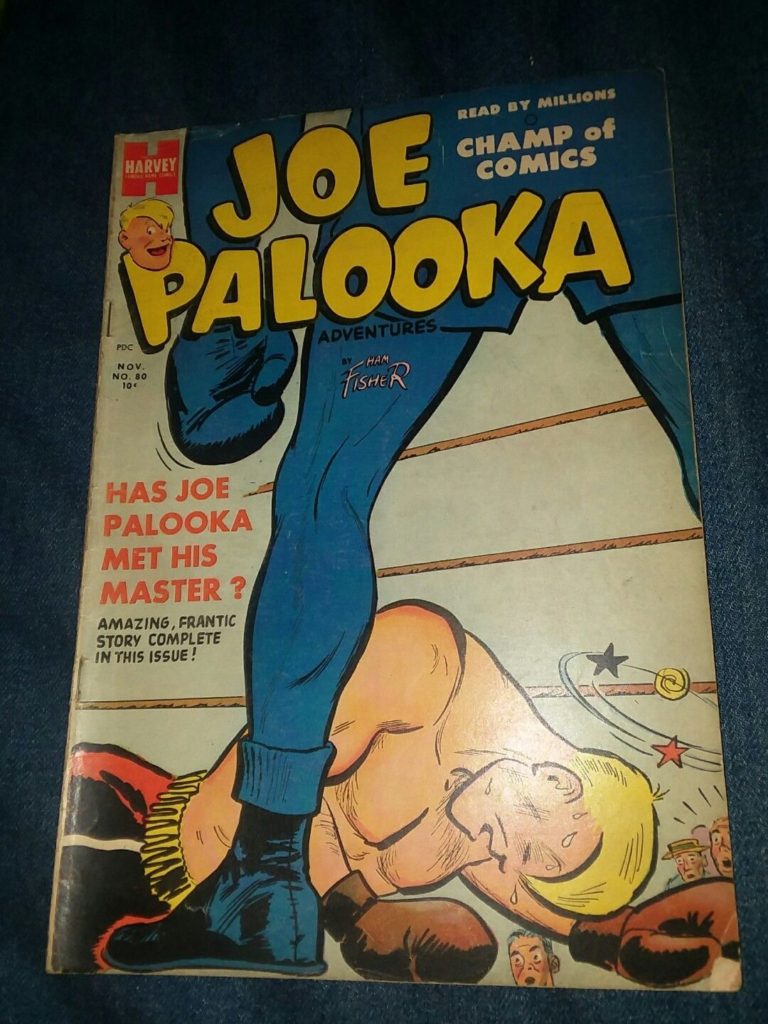

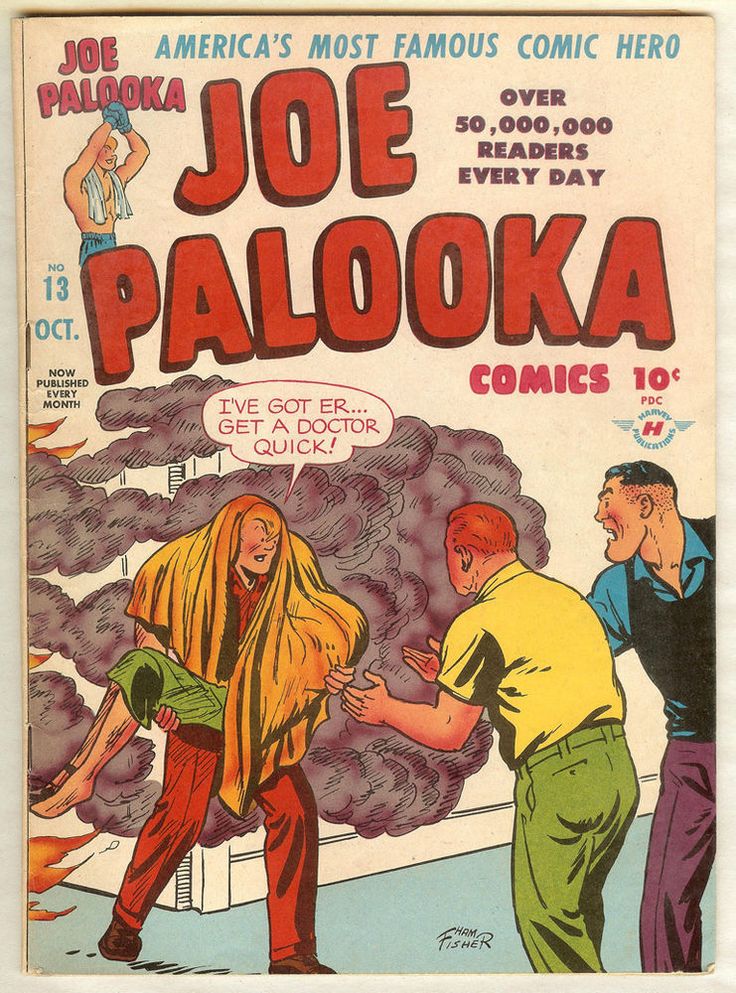

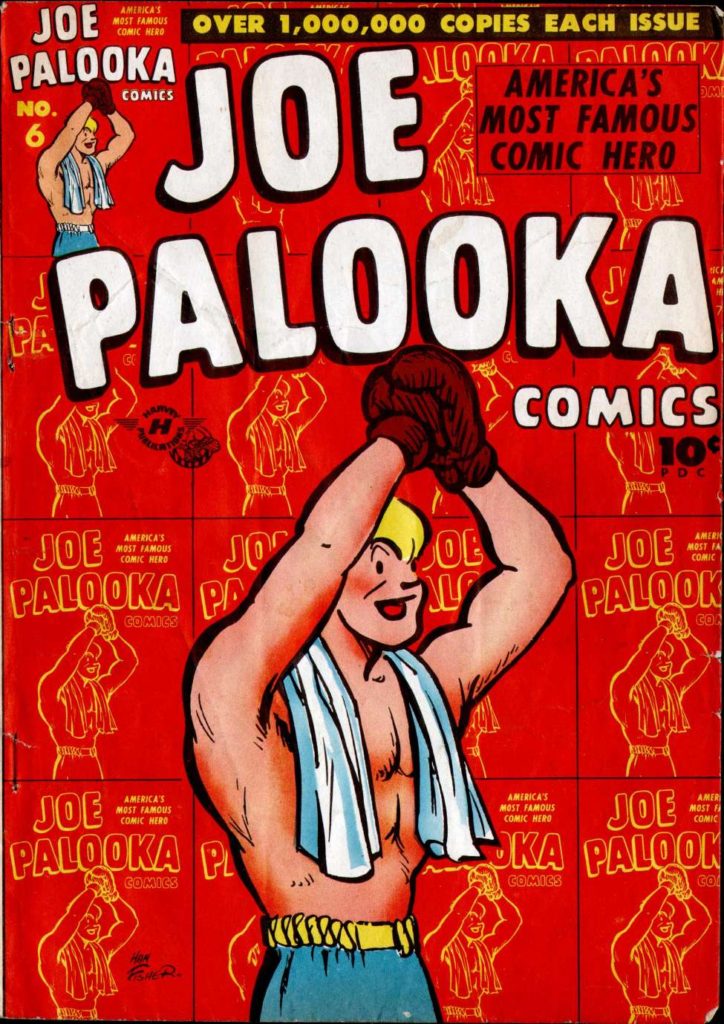

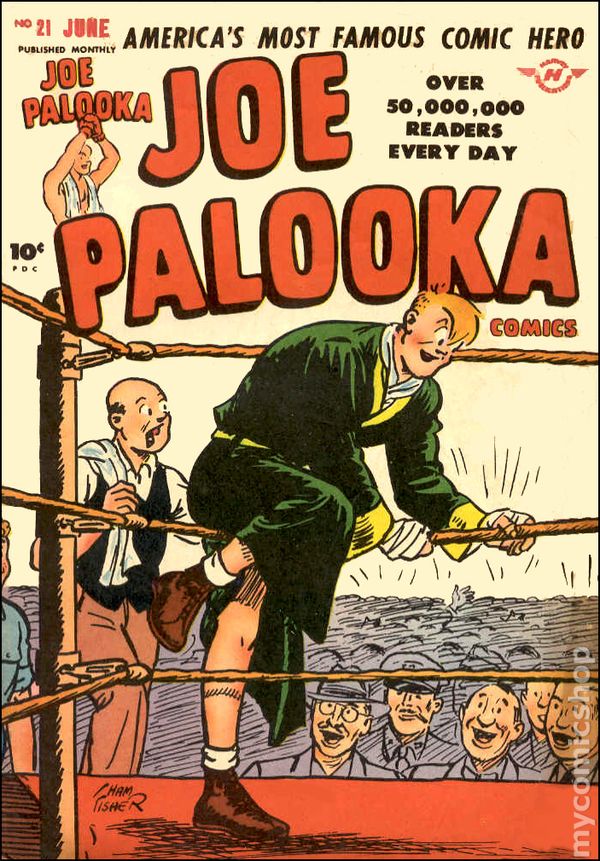

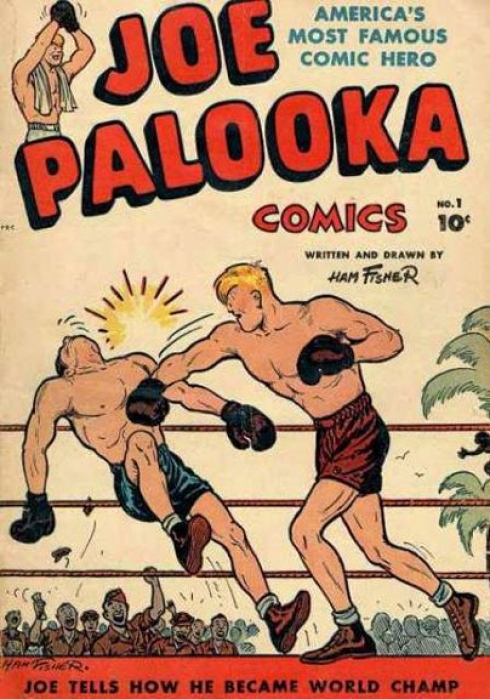

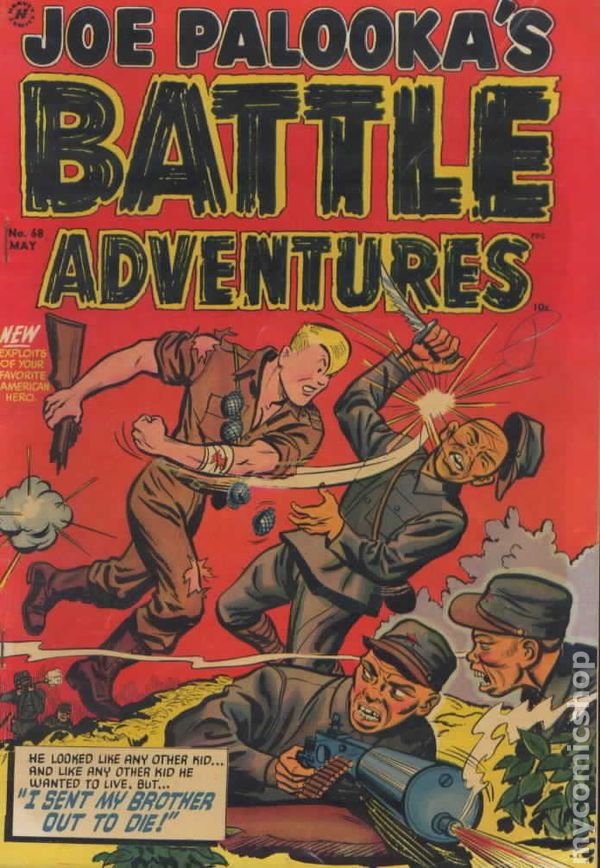

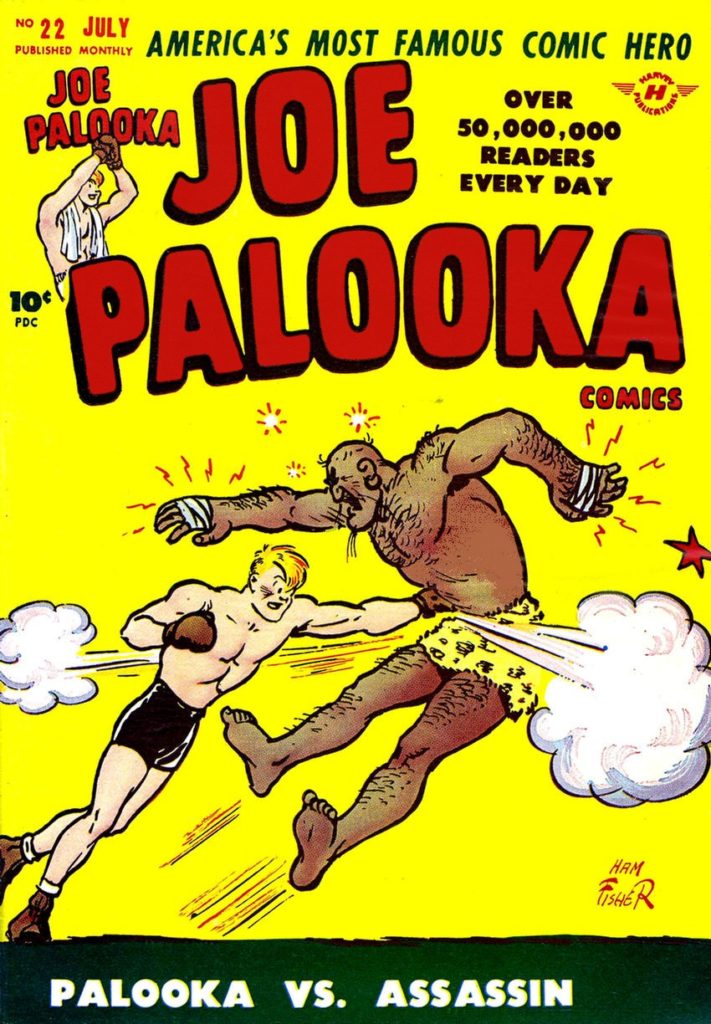

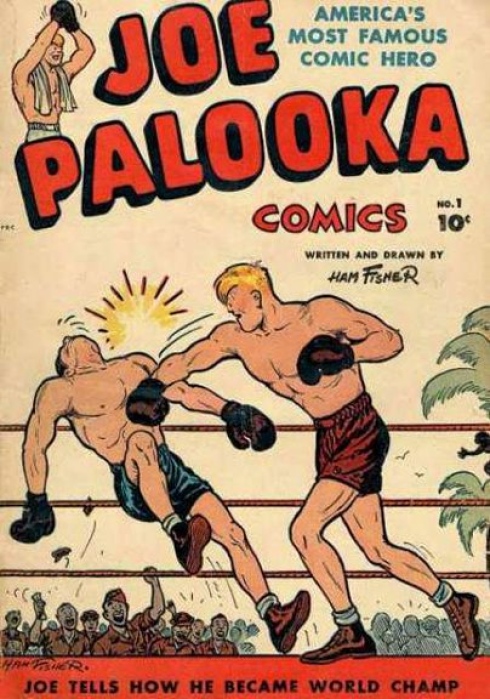

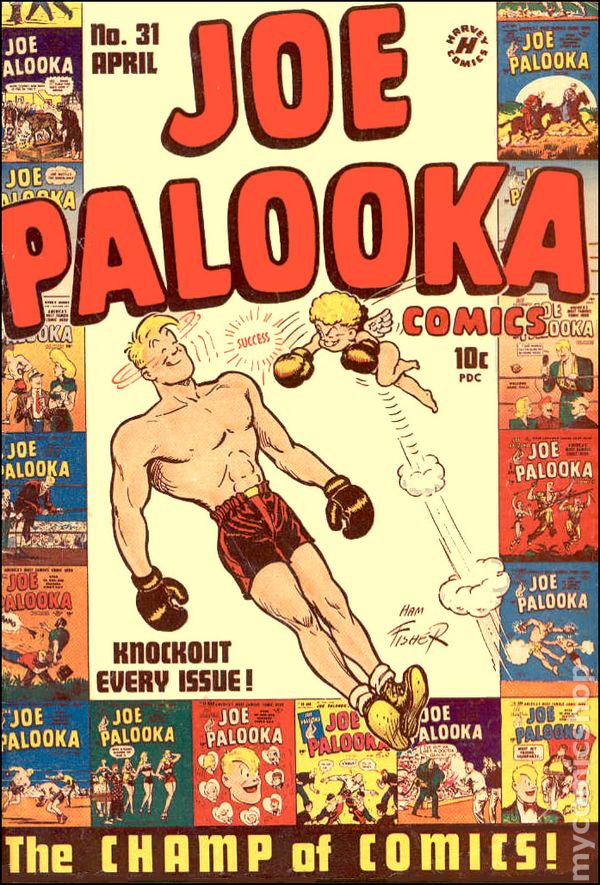

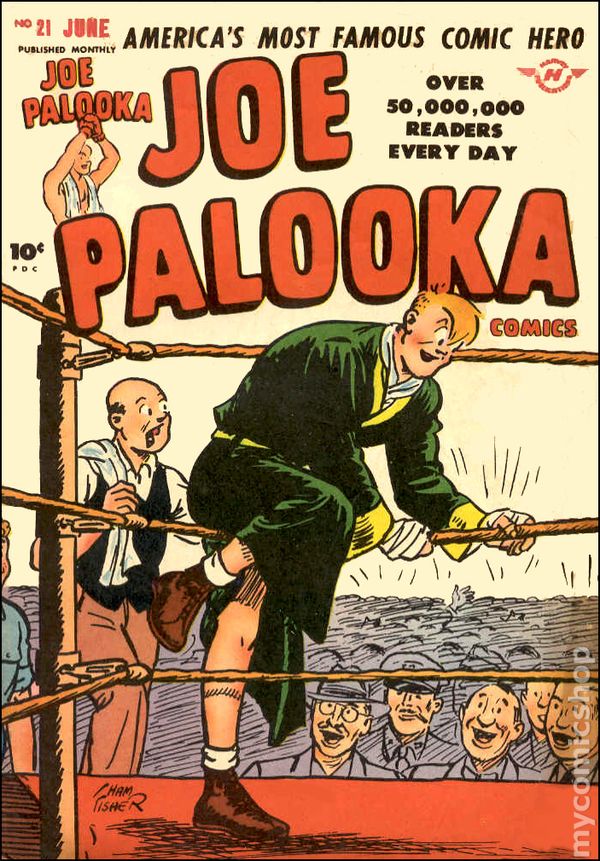

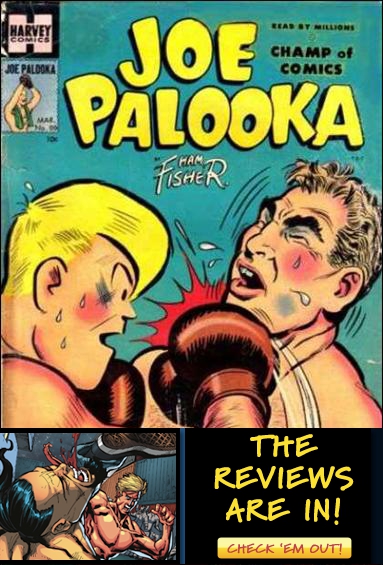

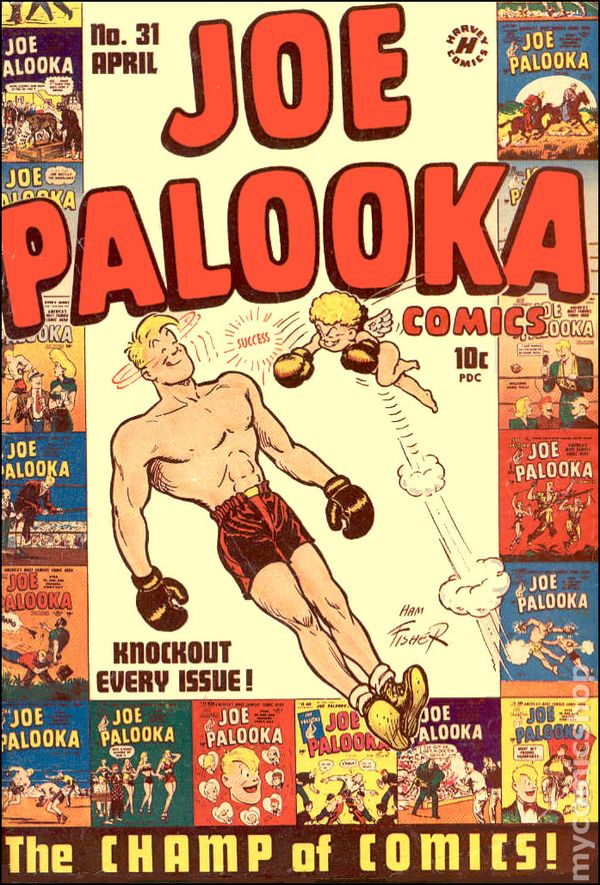

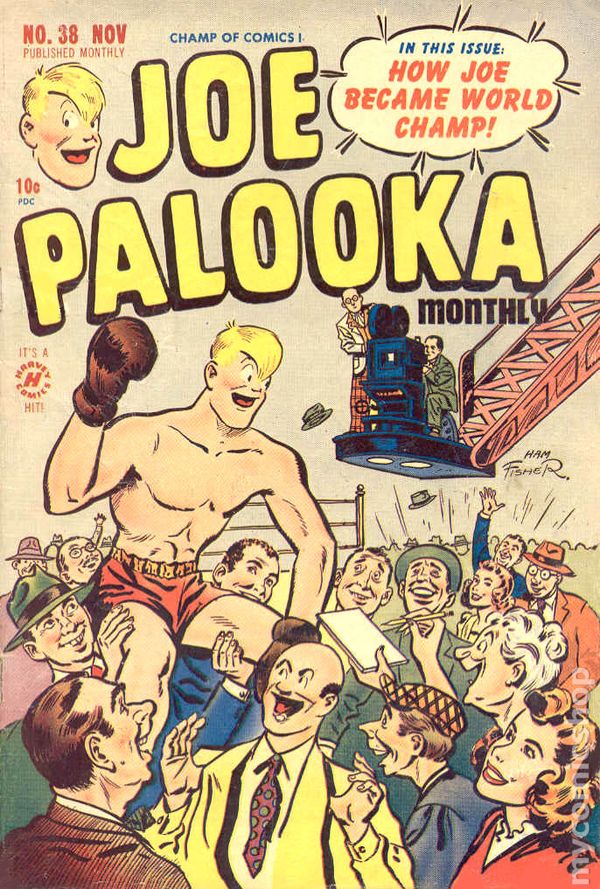

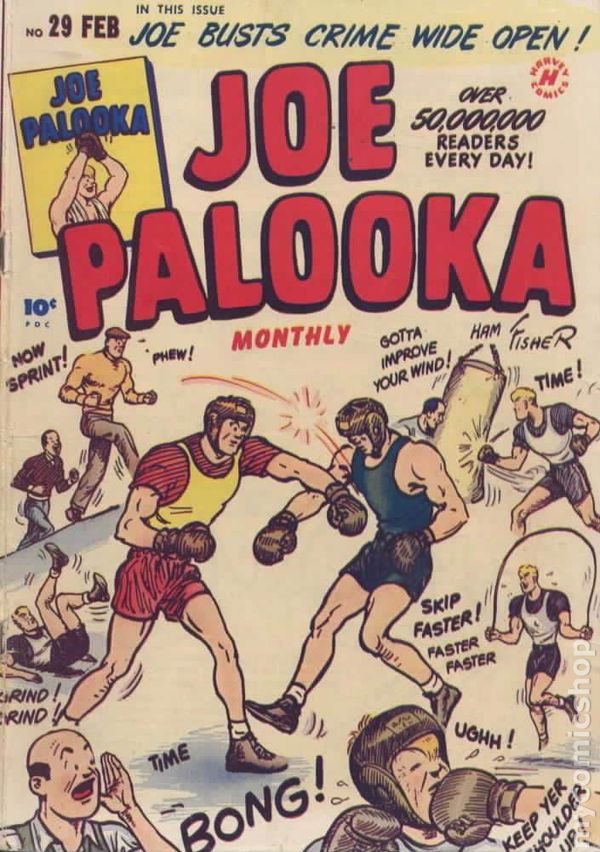

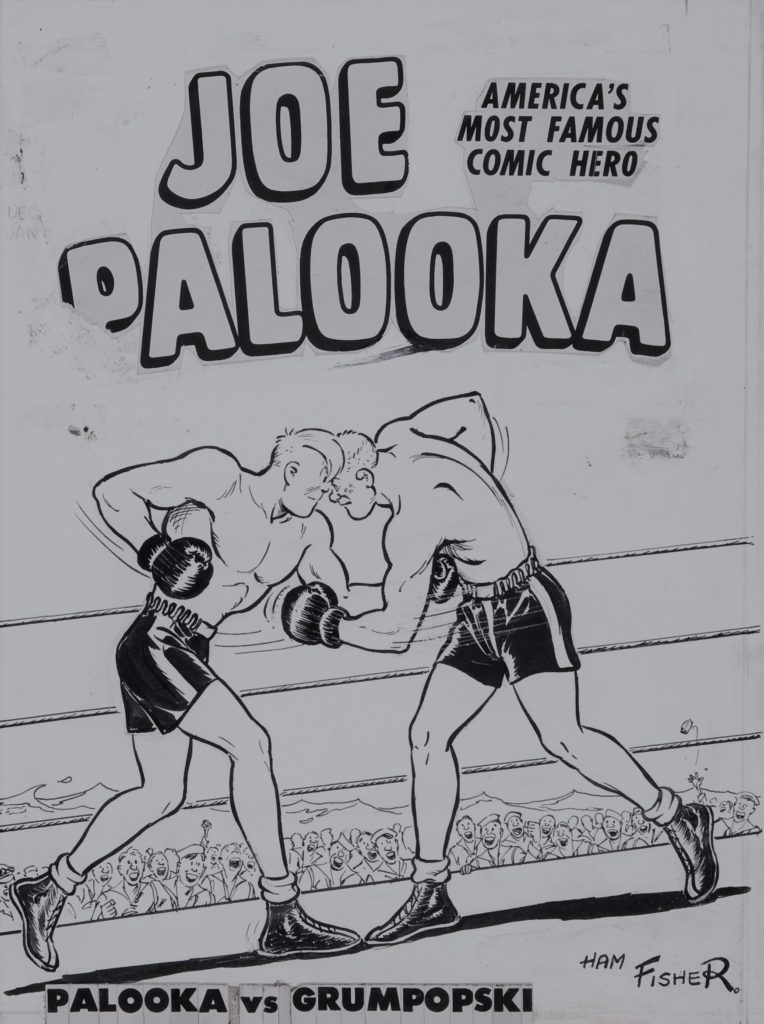

“Any buddy back home who’s spreadin’ intolerance against any person because of his race, creed or color is spreadin’ Nazi principles,” Joe said. Even after the war Joe Palooka remained popular. He was used in a U.S. Armed Forces comic book designed to help soldiers readjust to civilian life, and the same year the war ended (1945) was the same year the Joe Palooka comic book was launched. Dubbed “America’s Most Famous Comic Hero,” the issue sold for 10 cents and had the cover headline “Joe tells how he became world champ” below a photo of Joe knocking a man unconscious. Ringside ticket-holders are military men cheering him on. The comic book was published until 1961.

“Any buddy back home who’s spreadin’ intolerance against any person because of his race, creed or color is spreadin’ Nazi principles,” Joe said. Even after the war Joe Palooka remained popular. He was used in a U.S. Armed Forces comic book designed to help soldiers readjust to civilian life, and the same year the war ended (1945) was the same year the Joe Palooka comic book was launched. Dubbed “America’s Most Famous Comic Hero,” the issue sold for 10 cents and had the cover headline “Joe tells how he became world champ” below a photo of Joe knocking a man unconscious. Ringside ticket-holders are military men cheering him on. The comic book was published until 1961.

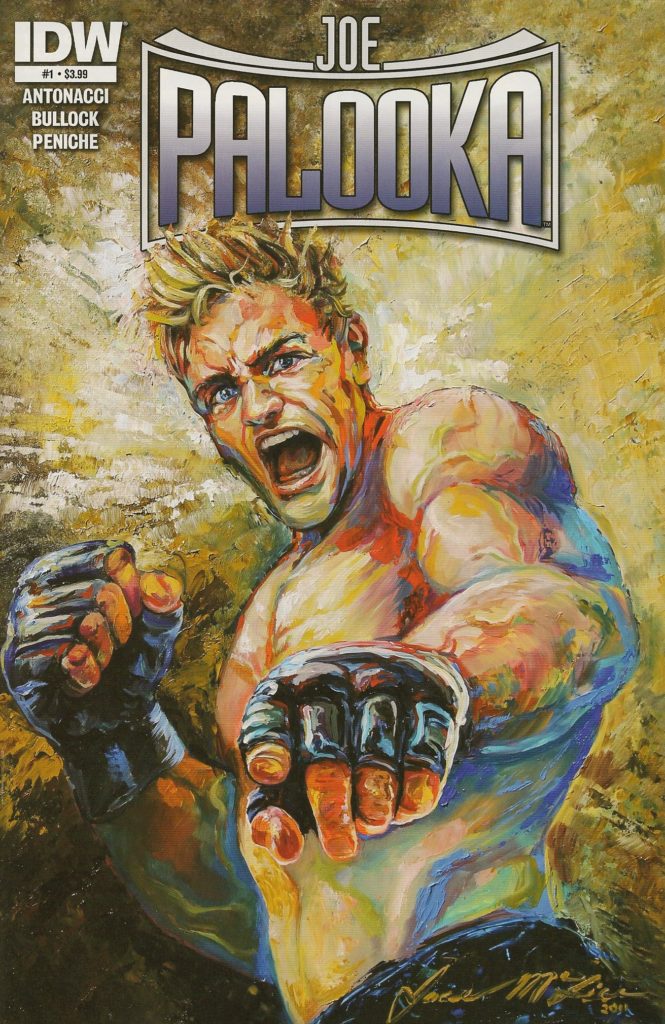

Boxing emcee Joe Antonacci revived the character in comic book form in 2012 after acquiring the trademark. However, he reinvented the character not as a boxing champion, but as a mixed martial arts fighter.

The character may have changed sports, but in Oolitic, Indiana, he still stands proud as the heavyweight boxing champion. Erected in 1948 in Bedford, the 10-foot , 20,000-pound statue was the effort of the Indiana limestone industry. The statue moved a few times after its dedication, eventually settling in Oolitic on Main Street between the post office and Town Hall. Dressed in boxing trunks and gym shoes, Joe is captured just before the start of a boxing match, with his falling fight robe looking almost like Superman’s cape.

Some passing by may not know who the statue depicts, but something must be said for the fact it still exists. Joe never fell victim to changing times or the wrecking ball. He remains standing in a world that is far different from its 1948 dedication, far different from Joe Palooka’s comic strip debut in 1930. He is a symbol of decency, a symbol of a simpler time in America. Many Americans can certainly learn a lesson from him.