Bare-Knuckle Corner

Bare-Knuckle Corner

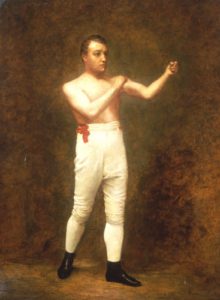

SAM “THE STALYBRIDGE” HURST

English Heavyweight Champion

Story by Mark Weisenmiller and John Rinaldi

We here in The USA Boxing News Bare Knuckle Corner Profiles Department have written, on numerous occasions, that many of said profilees were, in essence, more wrestlers than boxers, but we never have had quite an individual as we have here, who can be considered primarily a wrestler. Ladies and gentlemen, we present, and please meet, Sam Hurst, or “The Stalybridge Infant” as he was nick-named in his day.

Stalybridge is in Lancashire, England and that is where Hurst died on May 22, 1882. However, let us reverse polarity, as photographers say, and begin at the beginning. Born on March 13, 1832, Hurst moved to Stalybridge in 1857. There he went to work in the area’s iron foundry. Stalybridge was, and still is, steeped with all sorts of professions that use much manual labor. When Hurst was not employed at the foundry, he worked as a bouncer. This was easy work for him as, as per the times, he was a big man, both height-wise and weight-wise. He stood 6 foot, 2 ½ inches tall and weighed anywhere from 210 to 238 pounds.

This was also the time in his life where he began to wrestle for extra money. He discovered that he was good at it, for wrestling back then emphasized strength rather than quickness.

Yes, although he had success as a bare-knuckle boxer – from 1860 to 1862 – he was, in fact, the English Bare-Knuckle boxing champion, he had even more success as a rough and tumble wrestler. This was a man who, due to a fiery temper and his large physique, made him a man that his compatriots did not trifle with. Also, Hurst had an ego as large as his anatomy and he noticed that the rougher he got with an opponent during a wrestling match, the more the crowd cheered him onwards to even more violence.

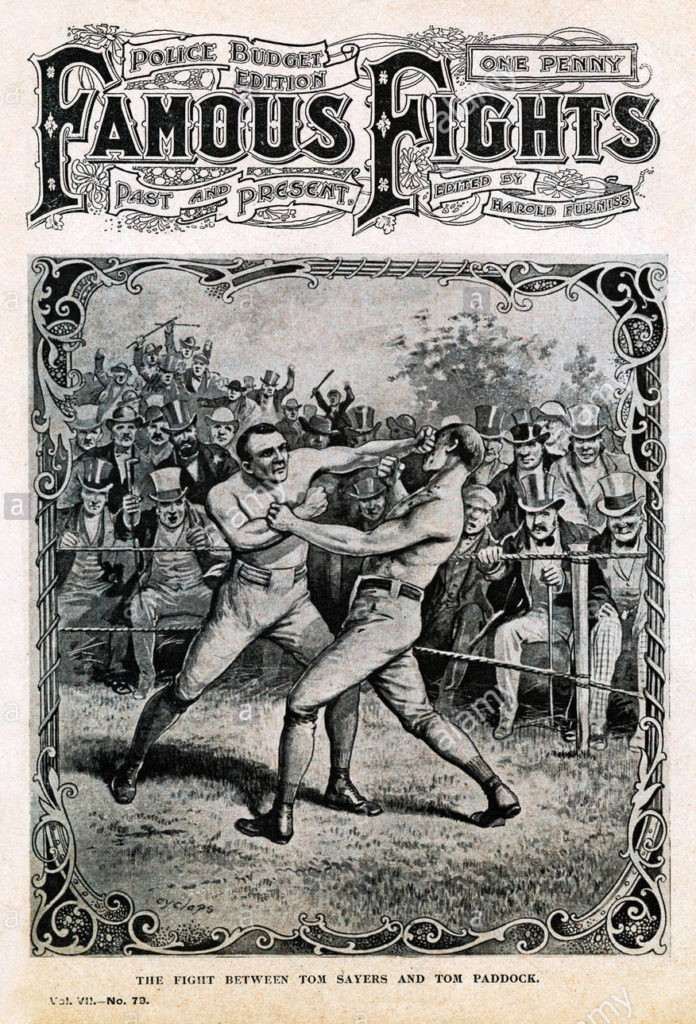

When he was 28, Sam found himself in a boxing match against Tom Paddock in a donnybrook held in Berkshire (he had all his boxing matches in England). This was for the vacant Heavyweight Championship of England.

Hurst’s fight against Paddock on November 5, 1860, was a one-sided affair as Sam came out swinging mighty rights and left hooks that repeatedly crashed against the skull of his rival. Hurst stormed forward with a hurricane of solid fists, while Paddock was too overwhelmed to mount any assault of his own.

Each of the first four rounds ended when Hurst pounded Paddock to the ground with his thunderous blows.

In the fifth round, it appeared that it had ended when Paddock slipped to the turf. Under London Prize Rules, if a combatant hits the ground either by being wrestled down, knocked down by a punch, or slipping down, the round is ended. Well, as Hurst journeyed back to his stool, Paddock jumped up and scampered after his man. Sam’s corner frantically began yelling, imploring him to turn around. Hurst then turned and as Paddock came forward to hit him, Sam beat him to the punch and fired a thudding right fist under Paddock’s heart!

Paddock’s eyes bulged as he crashed to the ground and was unable to rise as he writhed around the soil screaming in pain. The fight ended with Hurst becoming the new Bare-Knuckle Champion of England.

Afterwards, Paddock was carried to the departing train by his handlers as two of his ribs were shattered!

For the win, Hurst received £400.

Less than two weeks later – actually (to use a British favorite word), on November 19, 1860 – Hurst fell and broke his leg.

The following year on Waterloo Day, June 18, 1861, at Medway Island in Kent, Hurst made the first defense of his laurels against Jem Mace. The challenger at five-foot nine inches was over five inches smaller than Hurst and was outweighed by nearly 50 pounds. Very few gave Jem a chance to end the bout on his feet – let alone win.

As the two men threw their hat in the ring to begin the contest, the appearance of the two pugilists could not have been more different. Mace was wiry, tightly bound, and muscular, while the champion, though bigger, appeared fleshy, especially around his midsection.

The champ’s broken leg from seven months earlier clearly hampered his movements in the prizefight. With a noticeably limping leg, Hurst slowly lumbered forward. Seeing this, Mace used his sharp boxing skills and footwork to great success as he darted in and out and struck the champion with jolting fists to his face.

Throughout the first seven rounds, Mace picked apart the champion and ripped his features with slashing swings. Sam’s condition proved to be his downfall as he punched himself out with all the wasteful missing blows he launched in an attempt to pulverize his smaller rival. Mace carefully slipped, ducked, and blocked most of the fists that came his way, and in the process left Hurst utterly exhausted.

At the beginning of Round 8, the claret poured down Hurst’s face as he slowly shuffled towards the still-fresh challenger. As the huffing and puffing champion made a wild lunge at his adversary, Mace countered with a blistering array of shots, capped off with a right to the jaw that sent Hurst down flat on his back!

Barely stirring on the turf, Hurst was unconscious as the fight ended in the eighth round after 50 minutes of fighting.

As the now ex-champion was still on the ground being attended to by his handlers, the classy Mace passed his hat around to the crowd, where he collected £35 for the fallen prizefighter.

Hurst was a bruiser, while Mace was the better and more refined pugilist. The British boxing public (who, then as now, prefer boxers with colorful personalities) preferred things that way.

After the bout, Hurst decided to retire, although he did later fight in various exhibition matches, for which he was well paid.

Readers of many profiles here in the Bare-Knuckle Boxer Corner Department are mentally now guessing that they know the rest of the Sam Hurst story. That is: he becomes bored; turns to alcohol; meets a woman who emotionally and fiscally ruins him; become destitute, and then dies in disgrace. With this profile, that was not quite the case.

Sam married the daughter of a successful publican only a month after his loss to Mace. Sam then became the landlord of a Manchester public house one year later. Hurst, to everyone’s surprise but his own, turned out to be a talented businessman, so much so that three years later, he became the manager of a beerhouse in Hyde. As though all of this was not enough, in 1866, he became the owner of a tavern in Manchester.

Yet when he died, at the age of 50, he was a bankrupt. In Hurst’s case, the reason why this is so because he failed to keep up with business trends and because he was a person who tried to do everything himself. All of this made him so poor that, in the year before he died, 1881, Hurst became an itinerate cobbler.

From English Bare-Knuckle boxing champion to ending up as a menial laborer must have been traumatic for the egotistical Hurst. “Life,” as President John F. Kennedy frequently said, “is hard.”

JEM “THE BLACK DIAMOND” WARD

English Heavyweight Champion (1825-1831)

Story by Mark Weisenmiller and John Rinaldi

Jem Ward, born on Boxing Day (December 26), in 1800, is yet another profilee who started fighting in his early years. In Ward’s case, that age was 15. For six years, from 1825 to 1831, he was an English heavyweight champion, but boxing historians know him best for being the first known pugilist who, deliberately and purposefully, threw (i.e., lost) a bout for money. Another negative point about Ward: James Burke – a younger, stronger, and arguably overall more talented boxer than Ward -should have fought him, but Jem declined all such challenges.

Very little information exists about Ward’s childhood. What is known is his birth date and the fact that he was born In Bow, which is an area of East London and within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. As a young teenager, Ward, the oldest of seven children, was a star pupil at the sparring club in Bomley in Kent. Boxing, like baseball, is a sport in which reliable statistics have existed for centuries and based on that fact, “The Black Diamond” (as he was known) was 5’ 11” and weighed 76 kilograms (or 12 stone to use an old nomenclature of weight; this is 167 and one-half pounds).

When he was only 15, he won a match against George Robinson (a British boxer of whom little is known). This occurred on May 6, and six weeks later, he won a two-hour long match against Bill Wall in Limehouse Fields, England. He did not lose a contest for the next seven years, but do not be deceived into thinking that he was one of those boxers who had numerous fights during a year. Ward had one match in 1817, none in 1818, two in 1819, two in 1820, none in 1821, and three in 1822. All his matches at that time were in England.

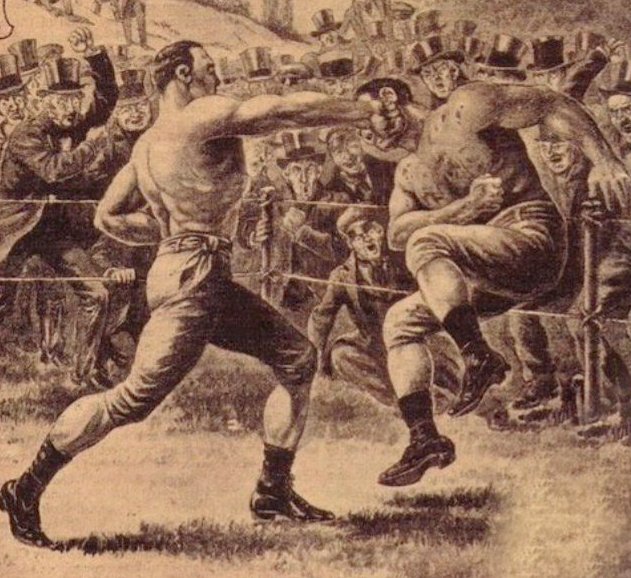

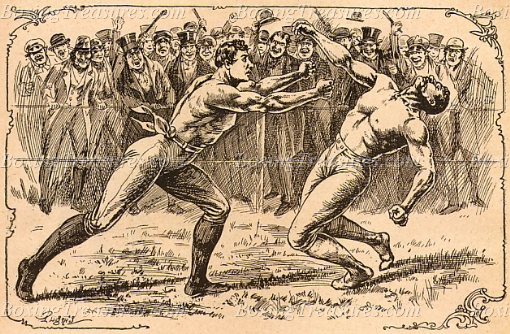

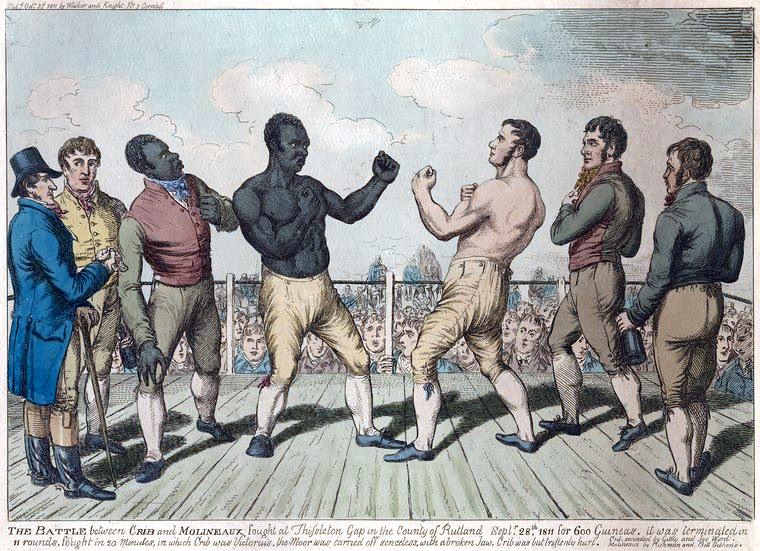

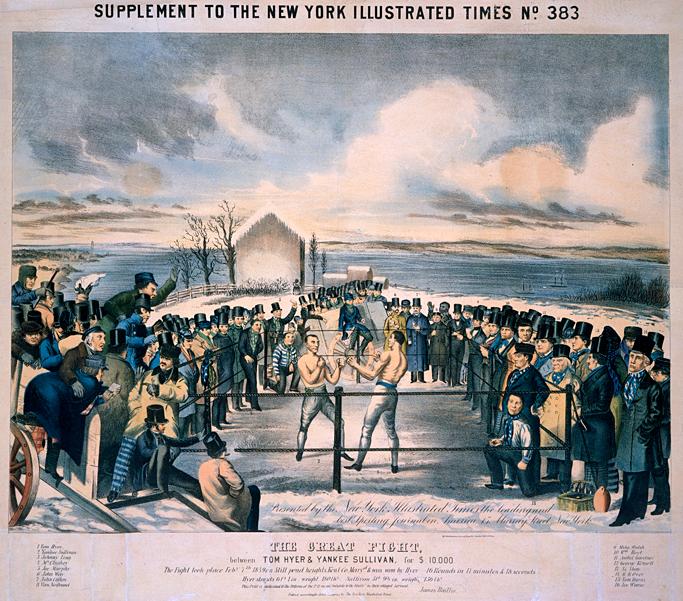

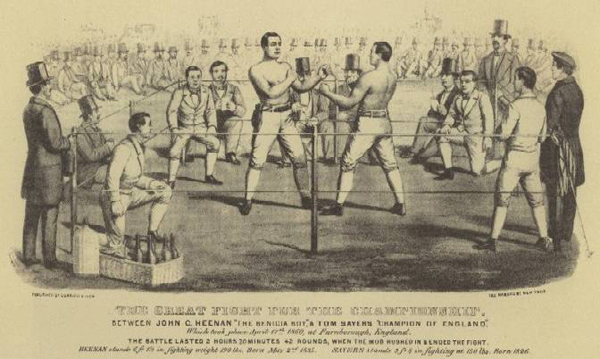

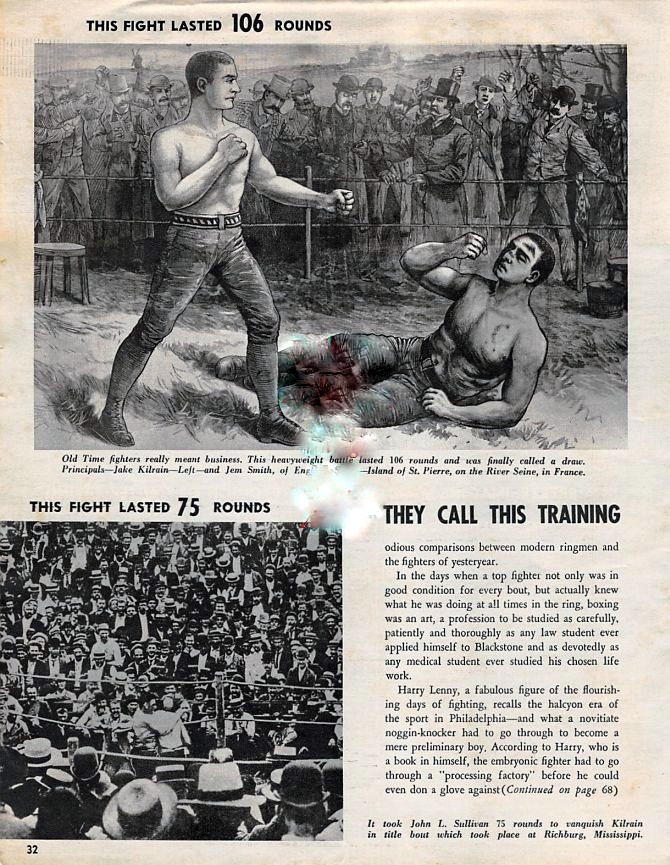

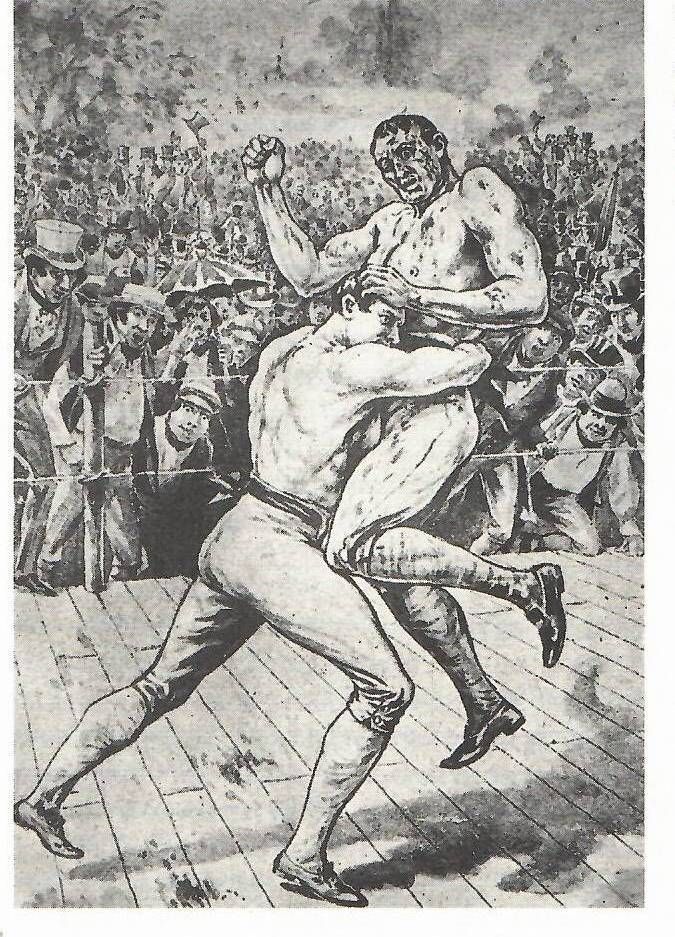

ChampIon Tom Cannon is being lift up by challenger Jem Ward in their 1825 British Heavyweight Title bout.

Ward’s loss, which occurred on October 22 against Bill Abbott in Mousley Hurst and lasted 22 rounds, seemed to snap Ward out of his pugilistic lethargy for he had a career high four bouts the following year. Ward won the first three of these matches, but lost the last (against Josh Hudson in a 36-minute long, 15 round bout).

Ward was one of those people who were lucky enough to find early in their lives something they excelled and then were fortunate enough to make a living at it. For most people in 19th century England, this was usually not the case. True, Ward began fighting early in life and sharpened his pugilistic skills as he aged, but just as some people have a natural gift for playing the piano, or calculus, or pottery, so Ward also seemed to have instinctive and natural gifts to excel at boxing.

What he definitely did not have was integrity; Ward was about as honest as a federal political lobbyist. Some of this may have been genetics. His brother, Nick, who was also a fighter, was well known for being a pugilist who would try to get away with dirty tactics during the course of a fight. Even by the wide parameters of 19th century British boxing, Nick was a shady character. Thus, questionable ethics was par for the course in the Ward family. Yet let us now give Jem Ward his well-deserved due; he was certainly dishonest himself.

History has clouded which of Ward’s bouts were purposefully thrown by the London-born boxer. Most boxing academics and historians, however, definitely agree that there were questionable goings-on in his 1822 fight against Bill Abbott. It was reported that those close to the bout heard Ward to remark to his foe, “Now, Bill, look sharp, hit me, and I’ll go down.” Supposedly right after that comment, Ward hit the floor.

All of this was way, way too much, again to use a clause previously used above, even by the wide parameters of 19th century British boxing. The English boxing oversight organization known as the Pugilistic Society investigated the matter. In doing so, the investigators discovered that Jem took 100 English pounds to purposefully lose the fight. The Pugilistic Society banned Ward for life from participating in any bout that was governed by it.

Traveling through the country, and incognito, Jem looked for any fight he could find; usually these came via county fairs. Ward also took bouts in other segments of society as well. He did this until July 19, 1825 at Warwick, when he defeated Tom Cannon in a ten-minute, 10-round bout to win the English Boxing Championship. Cannon, known as “The Great Gun of Windsor,” was no slouch. Tom became champion in 1824 when he defeated Josh Hudson in a 17-round long match. In his match against Ward, the two men fought in stifling heat in a brutal contest. In the tenth round, Cannon, 35, was appearing quite fatigued. Sensing his rival’s weakening condition, Ward, 24, who was exhausted himself, picked the champion up and slammed him into the boards. The challenger then fell on top of fallen title holder. Cannon’s handlers desperately tried to revive their unconscious charge and they violently shook him and even shot brandy up his nose! All the tactics failed and the referee, Squire Osbaldeston declared Ward the new champion of England. Although he emerged victorious, Ward was too weak to walk. It was reported that a local doctor bled Ward in his treatment, which nearly killed him!

Three days later at a benefit for Harry Holt at the Fives Court in Leicester Fields, Ward was awarded a championship belt for his win over Cannon. It was the first time that a boxing champion received a title belt. Cannon was on hand for the festivities.

“I have got it, and I mean to keep it,” Ward proclaimed to the crowd at the benefit. He later wrote a letter to Life in London stating, “In the interim, the various aspirants to the championship may contend with each other, and I shall be happy, at the expiration of the time specified, to accommodate the winner of the main.”

Somewhat surprisingly, Ward lost an 11-round bout to Peter Crawley on January 2, 1827, near Royston Heath in Cambridgeshire. Crawley, who was a butcher, went by the nickname of “Young Rump Steak” and his mighty fists certainly made his victims look like a side of beef afterwards.

Crawley entered the ring weighing 180 pounds to Ward’s 175. There were rumors that the 11-5 underdog was suffering from a hernia. Because of this, the challenger had to rely on his blows, instead of wrestling tactics and throws. Crawley, however, at 26, looked in tip-top condition.

It was a bloody and savage contest as both combatants battered one another with jolting blows and brutal throws. In the seventh round, Ward tossed the challenger to the floor with a cross-buttock move. The challenger barely stirred as his trainers worked on him. Surprisingly, Crawley manage to come to scratch and the battle continued.

By the eleventh round, Ward was completely sapped of any energy as he slowly plodded forward against his adversary. Suddenly, Crawley smashed a vicious left to the mouth of the champion that sent him crashing to the boards on his face. Ward’s seconds frantically lifted their man and feverishly worked on the unconscious champion. The bout lasted 26 minutes. It would take longer than that for Jem to regain his senses. After the bout, Crawley attempted to shake the hands of Ward, but he was still out cold. The ex-champ’s handlers carried him out of the ring and down the street to the Red Lion Inn, where he finally regained consciousness at 6 pm, which was 4 ½ hours after being knocked out! Luckily for Ward, he was only complaining of a headache afterwards and nothing much else.

Two days later, on January 4, 1827, Crawley announced his retirement. To Jem’s consternation, Crawley adamantly refused to give Ward a rematch. When Ward realized what had happened, Jem then reclaimed the championship.

Crowley, who wanted to achieve fame and prominence with the sport, had become a superstar with his great win over Ward and used his popularity to open a successful pub on Duke Street in West Smithfield called the Queens’s head and French Horn. Peter also was a well-know sportsman and in-demand referee.

Ward had one bout in 1828 and then came the scheduled 1829 bout against Simon Byrne.

The battle as set to occur in 1829 but, as Ward reneged on a previous promise to fight Byrne, Jem had to relinquish the championship. What actually happened was the following: Jem had promised to retire and present the championship belt to the winner of the James Burke-Simon Byrne bout. That did not take place.

Two years later, on July 12, 1931, at Walcote, Ireland, which is near Stratford upon Avon, Ward and Byrne finally met in the ring. During the 1 hour and 17 minutes, 33-round bout, Ward defeated his younger foe before an immense crowd of 20,000. While the champion entered the ring in his colors “blue and bird’s eye” looking to be in tremendous condition with ripping muscles, Byrne climbed into the ring in Irish green and yellow and appeared soft and tubby. Ward clobbered the challenger with pile-driving right hands to the head and ripping right uppercuts to the chin. Byrne did not do too much except repeatedly getting knocked down. By the end of 33 rounds, Simon’s features were all covered with lumps and blood poured from his nose and mouth. The challenger’s trainers had seen enough and called off the fight. Ward collected the £200 a side and promptly retired after the win.

Yet Jem’s life certainly was not over. He retired to Liverpool (some 130 years plus from when the indigenous seminal band, The Beatles, emerged from there) and ran the York Hotel. In his spare time, he was taught painting by his artist pal William Daniels. Eventually, Ward became so proficient and talented a painter that he had public exhibitions of his work.

To everybody’s surprise – most of all, his – Ward discovered that he had both musical and singing talents. When he was not painting, he was either singing; playing the flute or violin (he was naturally gifted at playing both) and performing as a singer during musical concerts. This creative second act of Ward’s life also led him to teach and train younger boxers.

Jem Ward died in in London on April 3, 1884.

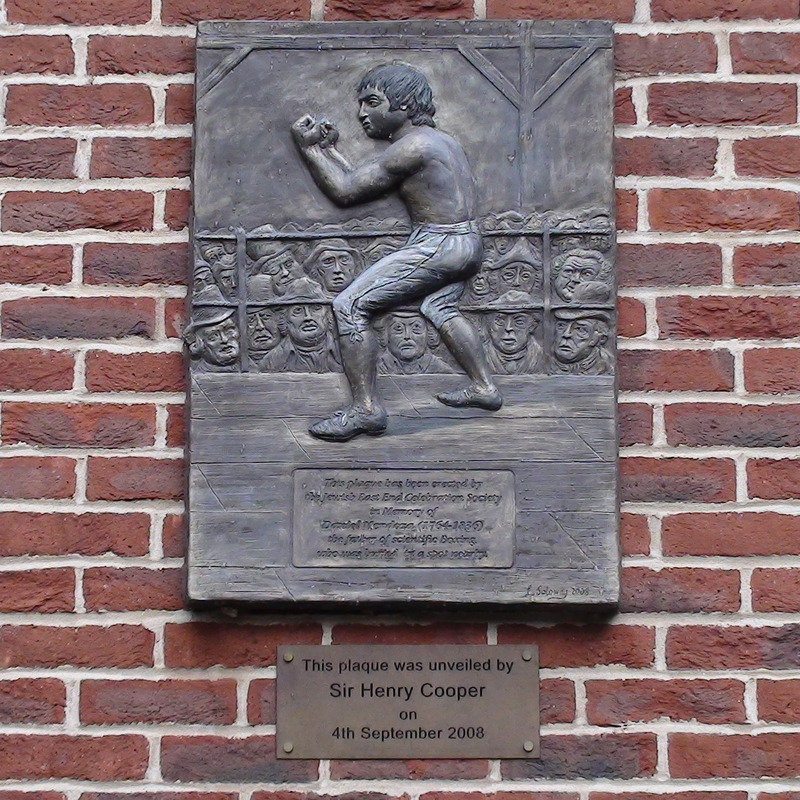

Daniel Mendoza

“The Best jewish Boxer in History”

Story by Mark Weisenmiller

Although there have been many famous Jewish pugilists in the long, long history of domestic and international boxing – names such as Max Baer, Barney Ross (who was the son of a rabbi), and Benny Leonard quickly come to mind – unquestionably the best Jewish boxer (in terms of having the most and long last effects on the sport) was Daniel “The Star of Israel” Mendoza.

This is so for many reasons: he was the first bare knuckle boxer to thoroughly study his opponents and quickly attack their weaknesses during the course of a match; he was the first to have a memorable quartet of matches against one opponent (Richard “The Gentlemen” Humphries, or also known as Humphreys), and he was the first to become a truly famous celebrity outside of the boxing world. That he did so, even though he was only champion for one year (from 1794 to 1795), is quite remarkable.

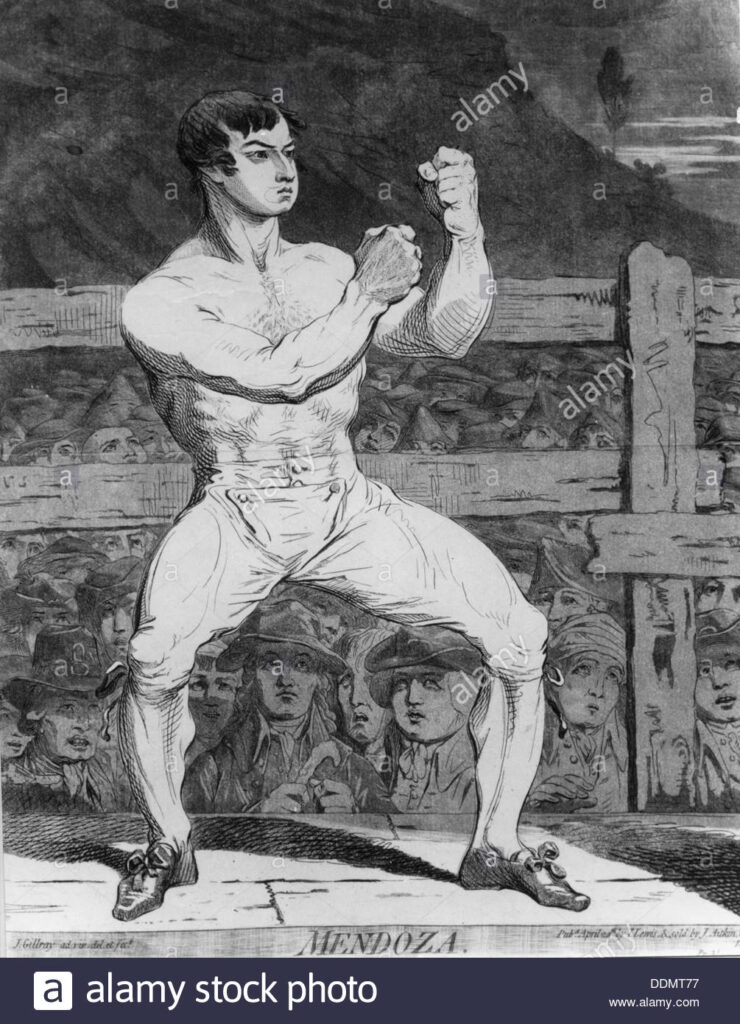

Born in Aldgate, which is located in the East End of London, on July 5, 1764, Mendoza was an English Spanish Jew who grew up to a height of only 5’ 7” and he never weighed more than 170 pounds during the course of his storied boxing career. From the very start of his bare knuckle boxing exploits, it was apparent that he was one of the smartest of pugilists both inside and outside of the ring.

In addition to developing a scientific style of boxing, which relied upon very quick reflexes and lightning-fast footwork, he was also the first boxer to have taken an active role in the promotion of his bouts and he even negotiated his own contracts. On this last point he must have done well for, after he retired, he opened a school to teach aspiring boxers everything that he knew. Mendoza was also the first English boxer to have fought overseas; he had bouts in Ireland, Scotland, and other nations.

Always a very literate man, he wrote his own autobiography. He did it himself; he employed no ghost writer. The book was entitled, simply “Memoirs” and for years after its publication, young boxers devoured it, trying to learn as much about the sweet science as possible. Anything that a boxing fan ever wanted to know about the days and way of English bare knuckle boxing is addressed by Mendoza in the book. Mendoza was the first bare knuckle boxer whose overall style of fighting could be described as graceful.

After his retirement, Mendoza kept himself in such pristine physical condition that, eleven years later, he came out of retirement to fight Harry Lee. Mendoza won the match which lasted 53 rounds on March 21, 1806 at Grinstead Green.

Mendoza’s last fight took place when he was, incredibly, 57 years-old. In a bout held on Banstead Downs, Surrey, he lost in 12 rounds to Tom Owen. That loss finally convinced Mendoza to retire from boxing for good. Sixteen years later, in early September of 1836, he died in London at the ripe old age of 72.

Yet, we are getting ahead of our chronological narrative. In his very first know match, against an opponent whose full time job was to shovel coal, Mendoza beat this man – whose history records as, simply, Harry The Coalheaver – in 40 minutes and 118 rounds in 1784. Mendoza dazzled the bout’s fans with his “Fancy Dan” footwork; his employment of quick, short, straight powerful jabs, and his use of defensive tactics. The last mentioned item was then considered unusual for it was the custom of the day for bare knuckle boxers to continuously be aggressive during the course of a bout.

After this first win, Mendoza must have finally had a chance to not worry about the future of his life’s work. Previous to this, he had tried to make a living in ways varying from being a glass cutter to even attempting stage acting. In a 1787 bout against Bill Warr, Mendoza defeated him in 23 rounds. Now it was time for his four matches against Humphries (records book also have his last name as Humphreys).

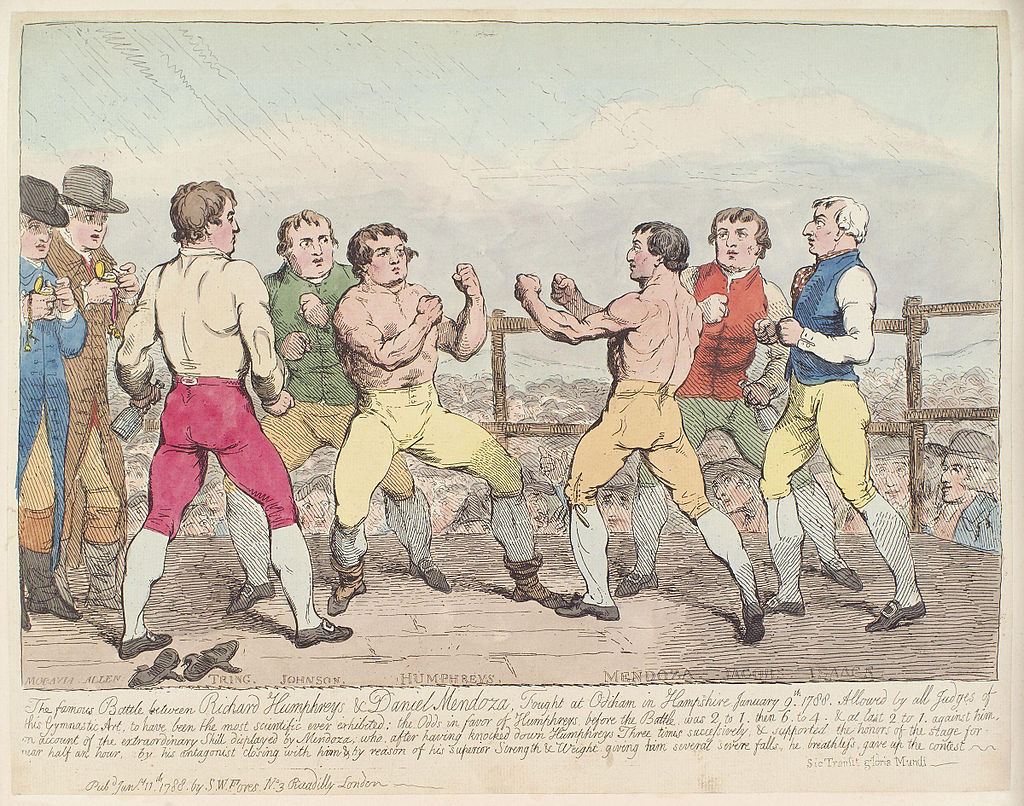

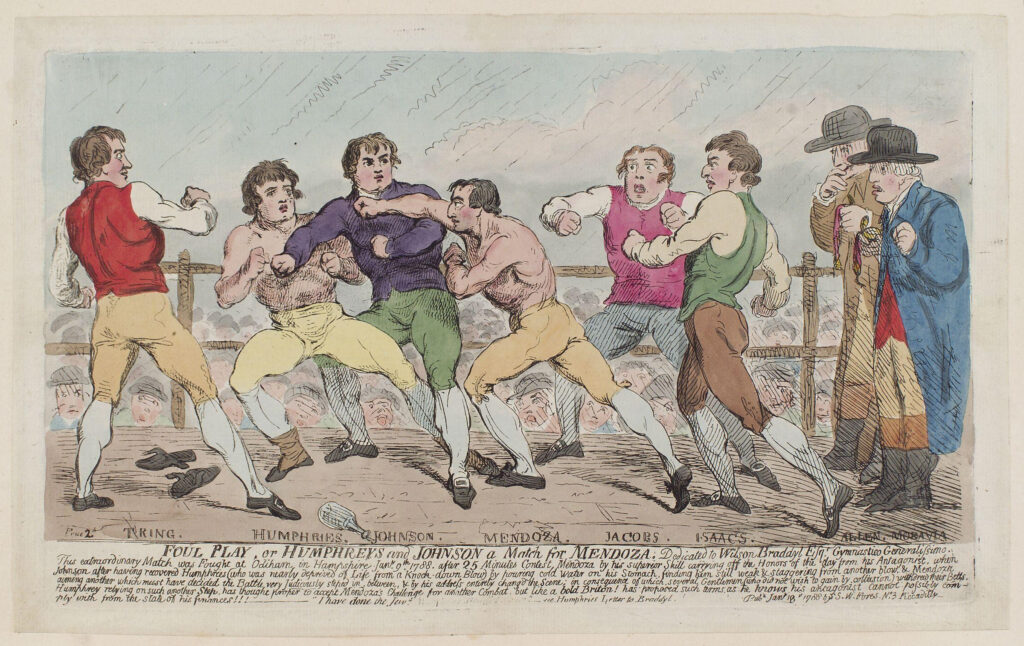

They were so tough for Mendoza that in the three consecutive years (1788-1790) that they fought, Mendoza made sure not to schedule matches against any other opponents. In other words, his only boxing opponent in that three-year stretch was Humphries. Humphries won the first match, the second match was forfeited, but then Mendoza won the last last two.

The first Mendoza-Humpries battle took place on September 9, 1787 and was over in 29 minutes when Mendoza was beaten to a pulp.

To get the ball rolling for the second bout with Humphries, Mendoza was quoted as saying in the papers, “Mr. Humphreys is afraid. He dares not meet me as a boxer, though he has the advantages of strength and age. Though a teacher of the art, he meanly shrinks from a public trial of that skill.”

Humprhries quickly issued a response to the press by stating, “Mendoza should make the same claim in the ring, where I vow to meet him.”

The ever wily Mendoza had what was then a unique idea for the second bout: he decided that the match would be held in a ring in a barn and, for the first known time in boxing history, fans who came to watch the match had to pay admission as they walked through a gate. Thus, Daniel Mendoza invented the pay-gate form of admission for not just boxing but all known sporting events. The second Mendoza-Humphries battle was also the first event to be promoted through the press. Both pugilists sent letters back and forth to the newspapers detailing their training and opinion of the upcoming contest. The excitement was at a fever pitch and by the time of the bout, stories were published in the London Times and six other popular British newspapers.

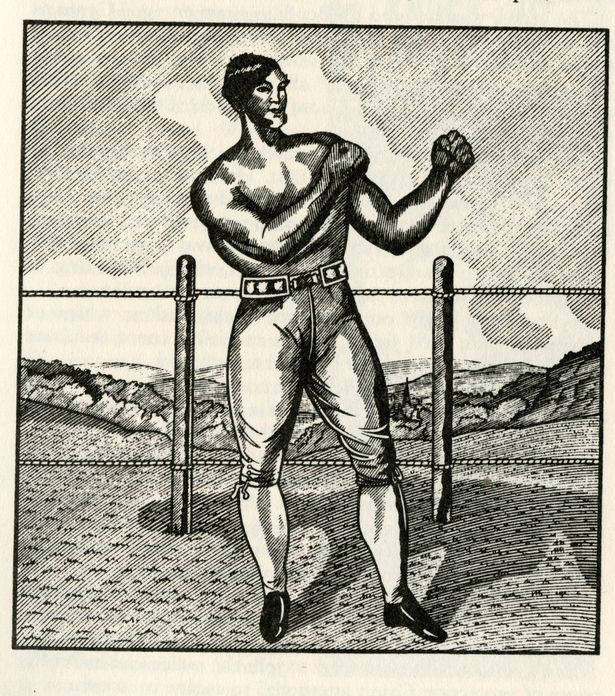

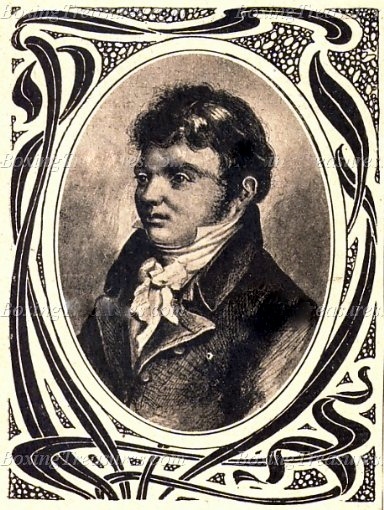

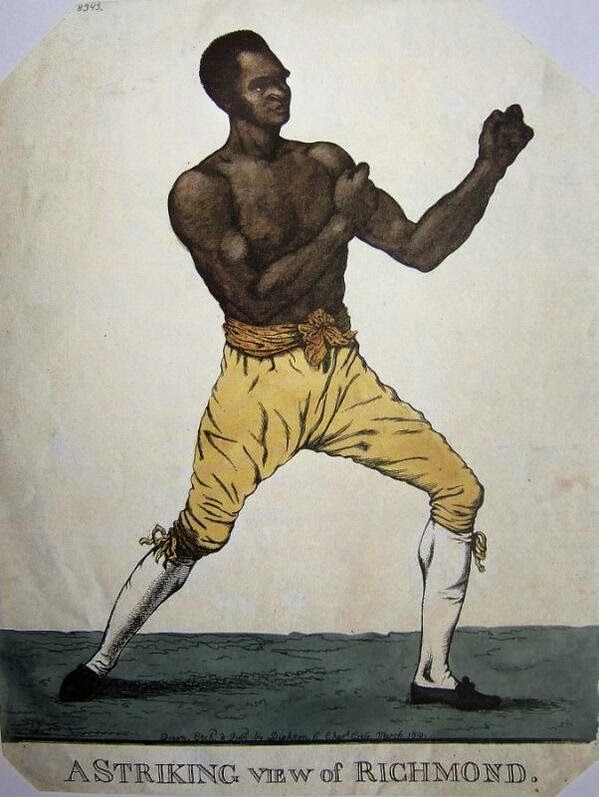

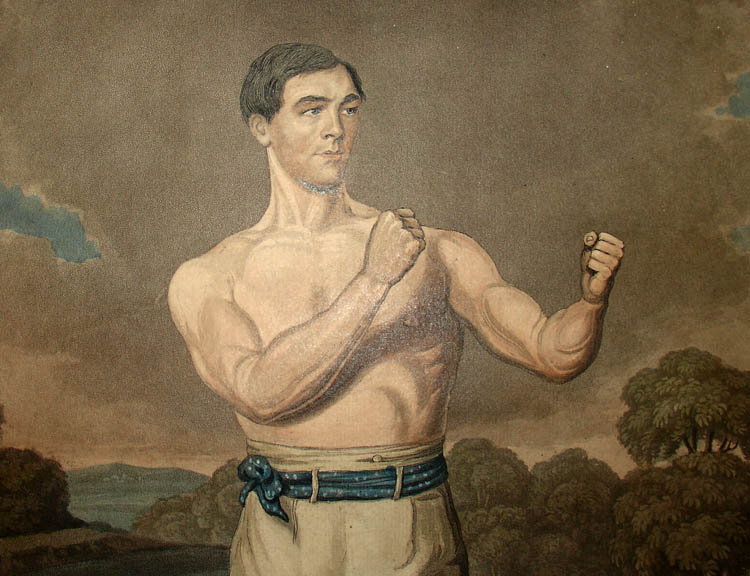

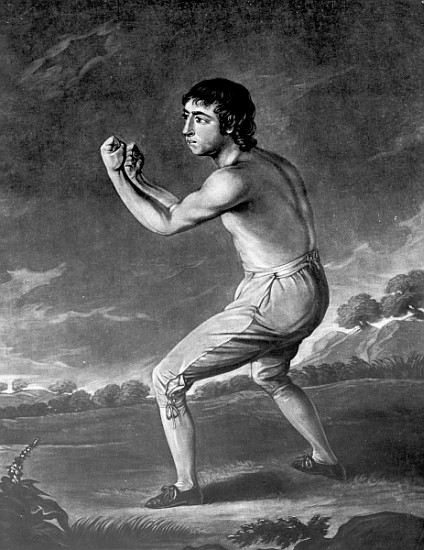

Daniel Mendoza, engraved by Henry Kinsbury, 1789 (litho) by Robineau, Charles Jean (d.c.1787) (after); lithograph; Private Collection; (add. info.: Daniel Mendoza (c.1765-1836) champion bare-knuckle boxer; the most scientific boxer ever known; Henry Kinsbury (1775-98).

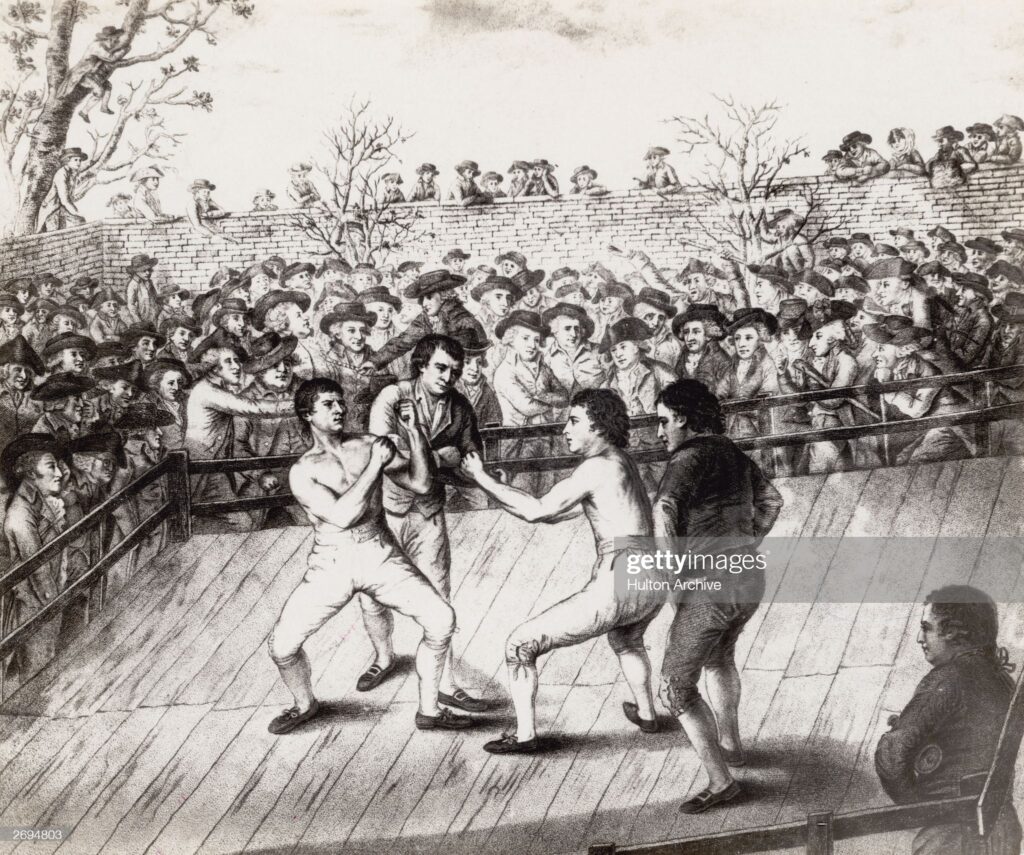

Humphries was a 2-1 favorite to win the fight, which took place on January 9, 1788 in Odiham, Hampshire before 10,000 paid spectators. Among the large crowd were the Duke of York and the Prince of Wales, who reportedly wagered £40,000 on the contest. The fight was halted when Humphries’ second, Tom Johnson, stepped into the ring and blocked a blow thrown by Mendoza. But according to Mendoza’s account afterwards, he had slipped on the wet boards of the prize ring, whereby he had sprained his ankle. The sprain prevented Mendoza from finishing the fight and he was required to forfeit.

The third match between the two prizefighters occurred on May 6, 1789 in Stilton, Huntingdonshire. Mendoza took up training quarters at the Essex home of Sir Thomas A. Price. In a new arena built especially for the fight, 3,000 fans were on hand to witness Mendoza methodically pummel Humphries with his effective footwork and jolting blows. By the 65th round, Humphreys and badly beaten up and dropped to the ground without being hit, which caused him to lose on a foul when he would not rise. The reason for the smaller crowd from the second battle was due to Huntingdonshire’s long distance from London. It was too much of a journey for fans to trek to.

With the win, the London Times declared Daniel Mendoza as the middleweight champion of England.

The fourth match with Humphries was on September 29, 1790 in Doncaster where the 5-4 favorite Mendoza finished his rival off in 72 rounds.

In 1792 and 1794 came Mendoza’s next matches. The two were against Bill Warr and Mendoza won both of them.

In 1795, Mendoza’s luck ran out when he fought John Jackson. In the match, which was held in Hornchurch, England, Jackson, who was taller and heavier than Mendoza, won in a rather brutal manner. With one hand, he held and pulled Mendoza’s long, black colored hair and with the other hand, Jackson pummeled Mendoza. The bout lasted nine rounds. Mendoza, as mentioned above, then announced and had his first retirement.

Yet the ever colorful life of Daniel Mendoza continued. At one point in his retirement, he toured in a circus where he gave boxing exhibitions. He also went on public sparring tours (where he was well paid for his efforts).

When he was not doing the above, Mendoza often hob-knobbed with English royalty. There was a practical reason for Mendoza to do so: he was often in debtors’ prison and, frequently when he met British royalty, he made it a point to plead with them not to have him thrown in debtors’ prison yet again.

Due to his unstable fiscal situation, and also due to the fact that despite a career in boxing, he managed to keep his good looks (he had dark, piercing eyes and classical facial features), Mendoza could turn on his considerable personable charm and ask friends for loans or money. As he was known for being a ladies’ man, Mendoza especially was talented at doing this with his many, many female conquests.

So, one could report, not only did he side step as a boxer, he also, in a way, side stepped through life. Yet Daniel Mendoza should not be remembered for such shady actions. Rather, this was the man who made bare knuckle boxing less of a freak show and more of a type of athletic science. In short, Daniel Mendoza was a boxing revolutionary.

Harry Broome

“The Birmingham Bomber”

Story by MARK WEISENMILLER

Birmingham, England has produced all sorts of notable people, but for our purposes here, we are focusing on a pugilist that went by the name of “The Birmingham Bomber” in the 19th Century. That is, Harry Broome, who for a five-ear span, from 1851 to 1856, was the Heavyweight Bare Knuckle Boxing Champion of England.

Henry Alfred Broome was born in 1826 in Birmingham and, due to genetics and/or fate, his vocation of being a boxer was per-destined, for he was the younger brother of Johnny Broome, who was never defeated in his respective pugilistic career. Johnny saw early in Harry’s life that he, too, had the skills and muscular physique to become a boxer and so Johnny trained Harry to do so.

In his fistic prime, Henry Alfred Broome stood at 5 ft. 10 in. and weighed between 136 and 178 pounds.

Immediately, it was clear to Johnny, and all other contemporaries of his in the British boxing world that Harry had plenty of talent. When he was just 17, he had his first two bouts. Both of these were held in London and were against Byng Stocks and Hal Mitchell, respectively. Both of these contests had the participants wearing gloves, which was unusual for that time in boxing history.

He had only one outing the following year, 1843, and it was held in Northfleet, Kent, England. There, he defeated Fred Mitchell in a bout that lasted 81 minutes. Once Broome won this contest, he became the Welterweight Division Champion of England. Young Master Broome, as the British would say, was only 18 years old and weighed 136 pounds for the bout. For his pugilistic efforts, he was awarded only £50 for the fight.

Broome defended his Welterweight Division Championship title in two fights against Joe Rowe in consecutive years (1844 and 1845). Broome won both bouts. The first fight was 81 rounds and lasted 90 minutes.

Broome now weighed approximately 145 pounds and his next fight – held on February 3, 1846 against Ben Terry in Shrivenham, England – proved to be his first controversial bout. The crowd that gathered to watch the fight was a loud, rambunctious (and now in hindsight, we can report) and a downright rude one – even judged by the wide latitude of British boxing match audiences back then. Broome probably fouled Terry, but the cowardly referee never called him on it, and this sent the ravenous crowd into such a riot that many of them flooded into the boxing ring. The referee, seeing what was about to happen, promptly ran from the ring and was never heard of in the British boxing world again. For his non-called foul, but more for the overall mayhem that he created with his Wildman stunt, Broome only received £5 for the fight. After one hour of bare knuckle boxing, the bout was declared a draw.

Broome’s questionable boxing shenanigans led him to, essentially, be blacklisted from British boxing for five years. Finally, in 1851, he had a bout against The Heavyweight Champion of England, William “The Tipton Slasher” Perry in Mildenhall, England. Broome now had a taste of his own medicine, so to write, for he was consistently fouled by Perry, so much so that after 33 minutes of fighting, not to mention his right eye consistently getting in the way of Perry’s right jabs, Broome won the bout when Perry punched him in his face when Broome was kneeling in front of Perry. Referee for the bout was former champion Peter Crowley. The fight ended in the 33rd round with Broome winning the title and earning £400.

Two years later, in 1853, in a bout in Brandon, England, against Henry Orme, Broome successfully defended his laurels. This two hour, 18 minutes long fight, which the champion won in 31 rounds, was held in the Shoreditch railroad station at the Eastern Counties Railway Complex. Both boxers were 27 years old at the time of the bout and both received £250 for their day’s work.

Harry Broome still was the champion of England, and he still was popular, but in all of the previous years, his face and body were knocked about, it quickly transformed him into an “old” man. His reflexes began to slow and once that happens to a boxer, his boxing career is doomed. A fight to be held in August of 1853 against Perry was scheduled, but not held. Ditto two years later, when Broome was twice booked to battle Tom Paddock, although each time he refused to do so. Broome simply refused to engage in both bouts.

Finally on May 19, 1856 in Manningtree, England, Broome fought Paddock. For an incredible 51 rounds – that is, 63 minutes – the two boxers engaged in an epic battle royale. The champion took an incredibly high number of punches, especially to the left side of his face. Broome’s face was swollen from being pummeled by Paddock’s fists all fight long. In Round 51, Paddock threw a right jab to Broome’s chest and it cleanly connected. That was, and is, a so-called heart punch – a blow thrown by a boxer whose intended target is his opponent’s heart. Broome went down and did not get back up.

While he was down and hearing a count being taken above him, Broome realized that he could not continue any more as a prizefighter. He immediately retired after the bout and became a pub owner. Careless with his money, due to developing a gambling problem, he soon became destitute.

Worse, due to being battered about during his boxing career, Broome’s health rapidly declined. Then his family’s finances were shattered due to spending their life savings on Broome’s medical expenses – there was no such thing as the National Health Service in England back then. Harry Broome died during the evening of November 2, 1865 in the London suburb of Soho from lung disease and edema at the age of 39. He was buried in the same tomb as his brother Johnny Broome.

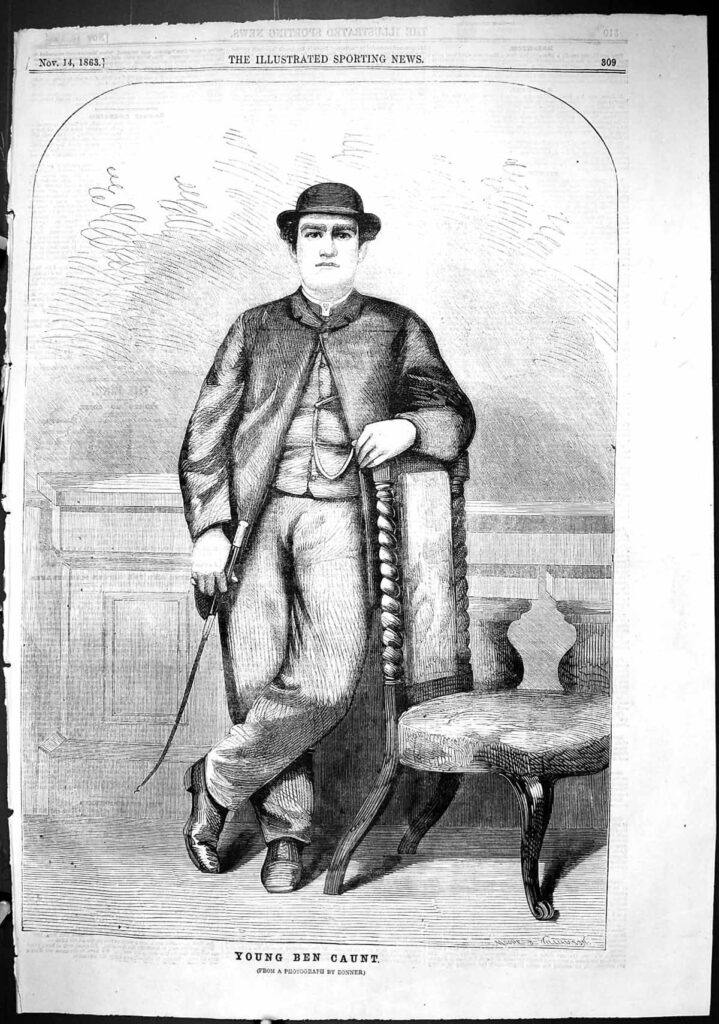

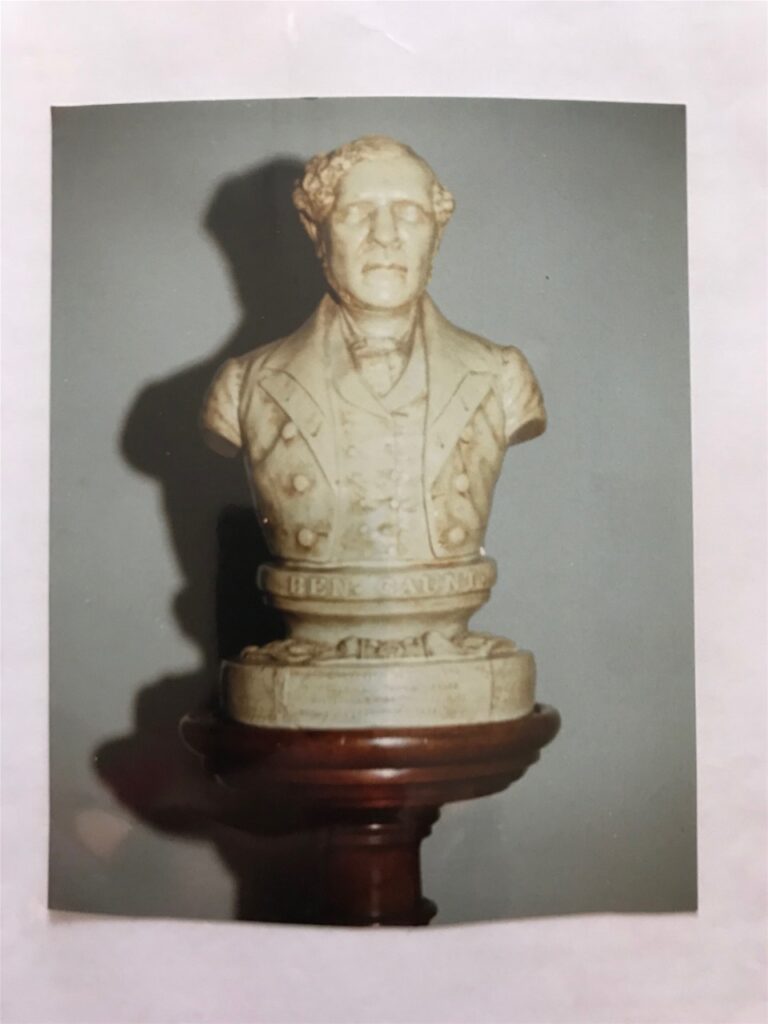

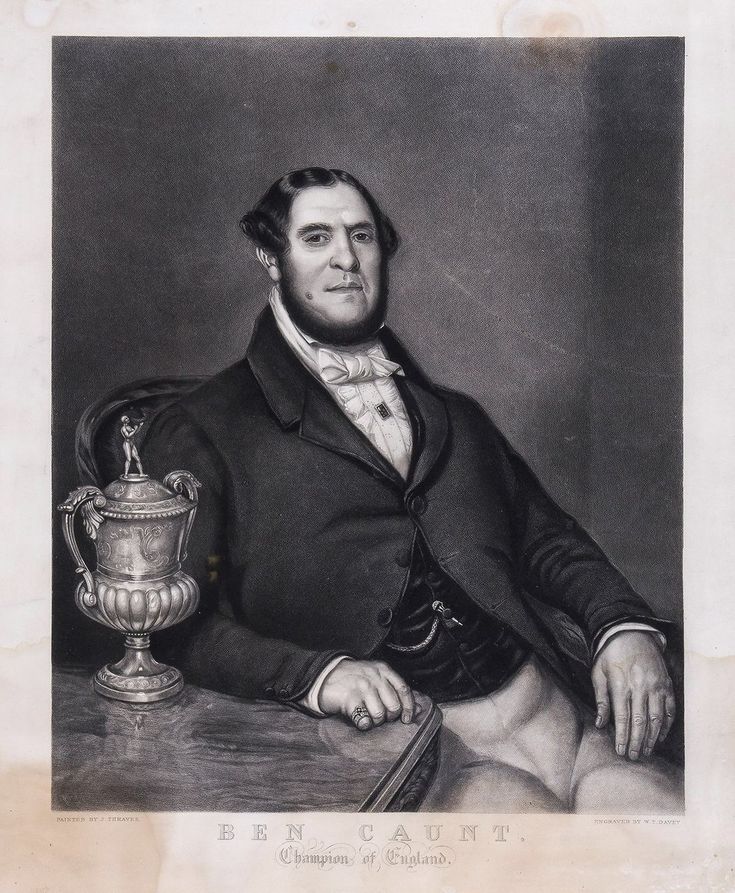

“BIG BEN” CAUNT

Immortalized by the Most Famous Bell and Clock in the World

Story by Mark Weisenmiller

Every day whether they know it or not, Londoners, either consciously or subconsciously, are indirectly aware of our profiled Bare Knuckle Champion. Big Ben is the bell and famous clock tower of the House of Parliament of England, and constantly and without fail, it has been ticking away the seconds, minutes, and hours since the 1859.

For whom were the bell and clock tower nick-named after? Answer: the late famed and successful bare knuckle pugilist Ben Caunt.

He stood 6’2” and during his prime days as a boxer weighed between 196 and 210 pounds. Not only was he what we today would describe as being a big-boned man, he was also marbled with muscle. There was very little body fat on this man.

When Big Ben – the bell, not the boxer – was first made public, no one had seen any bell quite so massive (it weighs 13 tons).

As is the unique personality trait of the English to constantly compare and measure people, places, and things (Americans have a habit of doing this as well), Londoners back in the 1800’s thought hard about trying to compare the bell to something big. The first thing that most of them thought of was the extremely popular bare knuckle pugilist Ben Caunt. Hence, the explanation of the nick-name of the most famous bell in the world (with the possible exception of the Liberty Bell located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

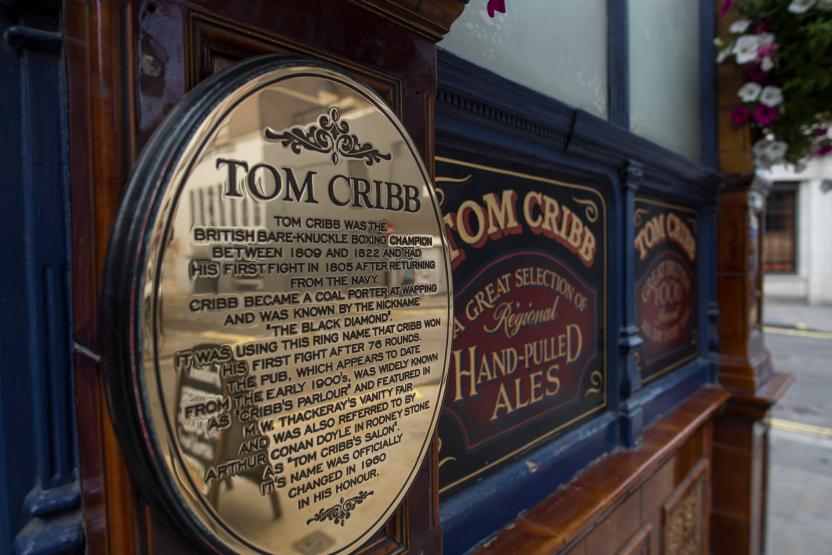

Like the bell which was nick-named after him, Caunt remained long popular as well. After he lost the English Boxing Championship to Nick Ward (the younger brother of Jem Ward, who has been profiled elsewhere in this section), “Big Ben” found his way across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States, and became rich by participating in numerous boxing exhibitions held all throughout the country. Sadly, Caunt died, at only the age of 45, on September 10, 1861 from pneumonia.

Despite his early death, Big Ben had a short, but memorable life – and his legend lives on every time the bell tolls in London.

From the beginning of his bare knuckle boxing career in the early 19th century, it was his ambition to become the English Bare Knuckle Boxing Champion. Unlike most people, who for various reasons do not accomplish their goals when they start a project, Benjamin Caunt DID accomplish his goal.

Caunt, who was born on March 22, 1815 in Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire, England, was the British Bare Knuckle Boxing Champion for a seven-year period (from 1838 to 1845), except for a short time span in 1841 when, as noted, he lost the title to Nick Ward.

While he was an iconic fighter, one is hard pressed to find something positive to write about Ben Caunt’s actual boxing abilities, because by today’s standards, he was a hopeless and slow galoot. Yet, he had great gumption; endurance, strength, and for such a big man (as per his time period), he was surprisingly durable in the many long bouts that he had (one of them lasted 101 rounds; this was fought in October 26, 1840 against Bill Brassey at Six Mile Bottom; Caunt won the bout).

Caunt began boxing when he was still in his teens (more specifically, 18; boxers beginning their bare knuckle boxing careers in their teens in England was common back then). His first notable fight occurred in July 23, 1835, in Nottingham, against William “Bendigo” Thompson. The end result gives us an indication of what kind of man Ben Caunt was. He lost the fight after the 22nd round when he fouled Thompson when the latter was sitting in his corner.

After two wins against inconsequential foes, “Big Ben” again fought Thompson; this match happened on April 3, 1838. This time, Caunt won when Thompson was disqualified when he fell without being hit by Ben. That occurred in Round 75 of the bout.

Fast forward to the year 1841 and to the aforementioned bout against Nick Ward. Caunt lost when he was disqualified for allegedly striking Ward with an illegal punch. When this occurred, the referee did not immediately disqualify Caunt, but a raucous audience forced the referee to do so. This bout took place on February 2 at Crookham Common.

On May 11 of same year at Long Marston, in the rematch, Caunt regained his championship when he beat Ward after the two went 35 rounds (the match lasted 47 minutes). Ever the egotist and adventurer, in September of 1841, Caunt traveled to the U.S. in an effort to fight Tom Hyer. When Hyer failed to reply, Caunt returned back to England the following year.

Time passed, and still William Thompson (whose boxing nickname was, inexplicably, “The Bold Bendigo”) still wanted to battle Caunt, so on September 9, 1845 at Stony Stratford, in a championship match, the two men again clashed. This contest would prove to be the most controversial of all of their matches.

In a battle that lasted 2 hours and 10 minutes (or 93 rounds), it ended when Caunt fell, but allegedly never was punched by Thompson. As per the British Prize Rules of the time, that meant that Caunt automatically lost the match; and Thompson became the new English Bare Knuckle Boxing Champion

For the rest of his life, “Big Ben” vociferously denied the end result of his last bout with Thompson. Caunt retired; found work as a farm field hand, and saving his money, bought and became the landlord of “The Coach and Horses” Inn located on St. Martin’s Lane in London. Tragically, two of his children died when they were killed in a fire that completely destroyed the establishment.

“Big Ben” Caunt never recovered from this calamity.

On September 21, 1857, at the age of 42, Caunt came out of retirement to face Nat Langham at the Home Circuit. The two gladiators battled for 60 brutal rounds, before the contest was declared a draw, because both participants were too exhausted to complete the bout.

Ben later caught pneumonia in the fall of 1861 and died in a house located on St. Martin’s Lane not far from where “The Coach and Horses” Inn once stood. He is buried in a grave located near in the St. Mary Magdalene churchyard in rural Hucknall, not far from his two children that died in the aforementioned fire.

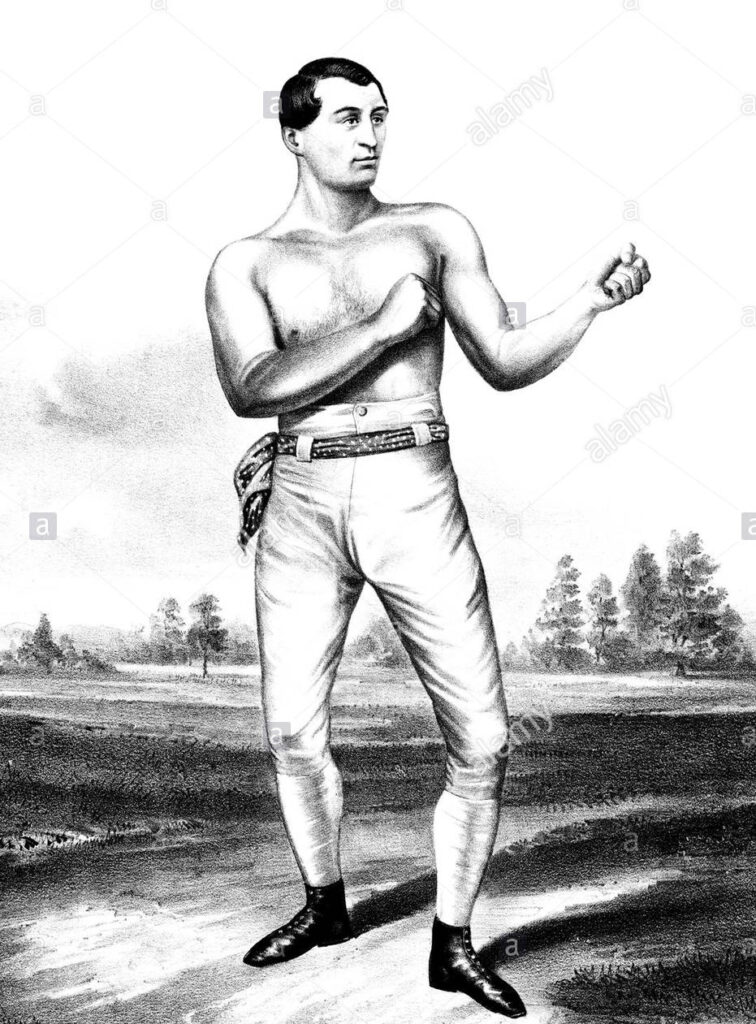

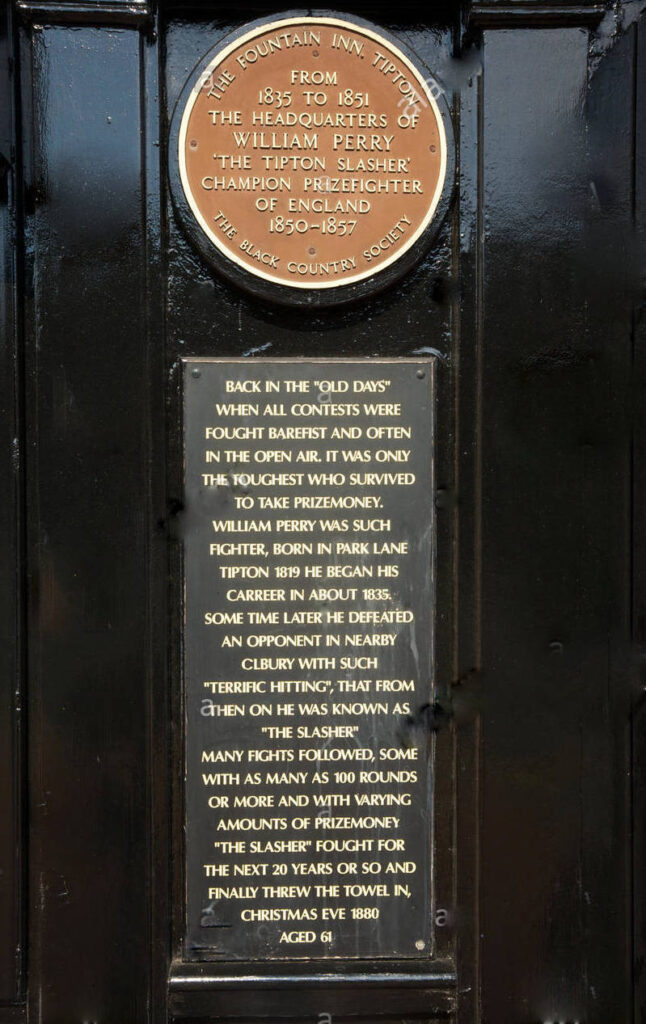

William Perry

The British Pugilist Who Perpetually Beat Up Foes

Story by Mark Weisenmiller

William Perry, the British bare knuckle boxer who was born and died in the 19th century in Staffordshire, England, shared some traits with William Perry, the 20th century National Football League (NFL) player star lineman: both were considered physically big men in their respective eras; both eventually became champions in their respective sports, and both had difficulty adjusting to their lives after they retired from active, professional, and violent competition.

William Perry, our profilee, was born on March 21, 1819 in the Staffordshire suburb of Tipton. Of course, this meant that the nick-name that he was tagged with at the start of his boxing career was “The Tipton Slasher.” That moniker made him sound like a crazed, cut-throat murderer and, by strange coincidence, he died in the same decade that the notorious knife-slashing murderer “Jack The Ripper” terrorized the people of Whitechapel in London.

Perry was born into a mining family as the third of five children. The fact that he was born into a mining family is no surprise for Staffordshire (it is now known as West Midlands) is an area well known for having numerous raw and natural materials in its earth. Such a life was (and still is, for those who live in the area and work in mining) difficult, and this way of living and overall lifestyle has been chronicled in innumerable novels by English writers.

A depiction of William Perry is on the front of the Fountain Inn, located in Tipton. The establishment is a traditional real ale pub in Tipton, providing locals and passing guests with a warm, cosy and welcoming pub. The pub has a lot of history behind it that goes back to the 1800’s. For example, the famous Tipton slasher William Perry used to train at the Fountain.

Few cold, hard, ascertainable facts about his childhood are known by boxing historians, but it is believed that at the age of 16, William worked in London as a navvy (that is, a laborer employed in building or excavating canals, roads, etc.). Such intense manual labor regularly produced muscular men and, as sometimes happens with people who work in said profession, it also produces individuals who are known for being vulgar. Thus, it’s not surprising that Perry was a bit of a neighborhood hooligan, who was well-known for being able to beat up anyone stupid enough to challenge him to a fight.

So, at age 16 and in Chelsea, Perry had his first professional fight. The date was November 3, 1835 and his opponent was Barney Dougherty. Perry defeated him in seven rounds. Then he defeated, in the same number of rounds, a brawler named Ben Spilsbury in a bout held in Oldbury. This fight was followed by a brutal one-hour long (31 rounds) bout, at Wolverhampton, against Jem Scunner.

Perry won that bout also; all of his fights were held in England. Next came two titanic matches against a virtual sequoia tree of a man. His name was Charles Freeman and he weighed 276 pounds and stood a towering 6 ft., 10 ½ inches tall. Freeman was an American who was managed by Ben Caunt.

So Caunt and Freeman made heir way to Sawbridgeworth and there, on a cold and frosty December 10, 1842, Perry and Freeman went at it. For more than two hours, “The Tipton Slasher” and the American Freeman pounded away on each other. The match ended in a draw when the cover of night forced the boxers to quit.

Both men desperately wanted to win the contest, so it was decided that ten days hence, at Cliff Marshes along the Thames River, the match would continue. This time, in a bout that lasted 39 minutes, or 37 rounds, Perry – quite oddly – fell, even though Freeman never laid a fist on him, and never got back up.

Perry was what we would call today a loudmouth: rude, gregarious, loud, a vulgarian. He also used to love to proclaim that he was the British boxing champion even when he was not and even though no sanctifying boxing club or organization then existed which could grant him such an honor. Even after he lost the bout to Freeman he still boasted that, in his (Perry’s) mind, Freeman was not really the champion because – again, in Perry’s viewpoint – Freeman never really hit him with a punch. Perhaps wishing to remain champion, and secretly fearing the tough bare knuckle boxer from Tipton, Freeman never granted Perry another bout even though Perry very much wanted one.

Next for “The Tipton Slasher” came a trio of matches against Tass Parker. All three of these bouts lasted significant amounts of time. The first was a draw lasting 94 minutes, or 67 rounds. The middle match resulted in a win by Perry over an exhausted Parker in a fight that lasted an incredible 133 (!) rounds. Perry won their last bout as well, which lasted 27 minutes, or 23 rounds.

Perry then defeated Tom Paddock in a 42 minutes long (22 rounds) match in Woking on December 17, 1850. William enjoyed showing his considerable boxing talents in the annual Christmas month of December. Since Paddock had been the champion, and he had defeated him, the loud mouthed Perry was even more locally boisterous and annoyingly told anyone and everyone in his general vicinity that he was England’s boxing champion. Perry then lost the title in a September, 29, 1851 match against Harry Broome in Mildenhall.

Even though William Perry’s professional boxing career was made up of only 11 known bouts, and although he was a popular champion and kept himself in excellent physical shape, these numerous very, very long matches began to take their toll on him. By the time of his last match – held on June 16, 1857 at the Isle Of Grain in Kent – against the immortal Tom Sayers – Perry was a shell of his former sporting self. His reflexes had slowed considerably; he had a noticeable gut, and his face, due to being hit innumerable times in his boxing career, resembled a slab of raw roast beef. The match was held on a barge boat moored in the Thames River.

Perry was so out of shape for the last match of his career that he outweighed Sayers by 50 pounds. In the tenth round (the fight had already lasted and incredible one hour and 42 minutes), Sayers hit Perry with a strong, straight, right jab to Perry’s upper lip. Immediately the lip split open and blood spewed forth. Despite Perry gallantly wanting to continue, his manager and trainer knew a serious injury when they saw one and they immediately called an end to the bout.

The Sayers-Perry fight was so popular that the famed poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) featured the battle in his poem “A Likeness” as it reads:

Some people hang portraits up

In a room where they dine or sup:

And the wife clinks tea-things under,

And her cousin, he stirs his cup,

Asks “Who was the lady, I wonder?”

“‘Tis a daub John bought at a sale,”

Quoth the wife,—looks black as thunder:

“What a shade beneath her nose!

“Snuff-taking, I suppose,—”

Adds the cousin, while John’s corns ail.

Or else, there’s no wife in the case,

But the portrait’s queen of the place,

Alone mid the other spoils

Of youth,—masks, gloves and foils,

And pipe-sticks, rose, cherry-tree, jasmine,

And the long whip, the tandem-lasher,

And the cast from a fist (“not, alas! mine,

“But my master’s, the Tipton Slasher”),

And the cards where pistol-balls mark ace,

And a satin shoe used for cigar-case,

And the chamois-horns (“shot in the Chablais”)

And prints—Rarey drumming on Cruiser,

And Sayers, our champion, the bruiser,

And the little edition of Rabelais:

Where a friend, with both hands in his pockets,

May saunter up close to examine it,

And remark a good deal of Jane Lamb in it,

“But the eyes are half out of their sockets;

“That hair’s not so bad, where the gloss is,

“But they’ve made the girl’s nose a proboscis:

“Jane Lamb, that we danced with at Vichy!

“What, is not she Jane? Then, who is she?”

All that I own is a print,

An etching, a mezzotint;

‘Tis a study, a fancy, a fiction,

Yet a fact (take my conviction)

Because it has more than a hint

Of a certain face, I never

Saw elsewhere touch or trace of

In women I’ve seen the face of:

Just an etching, and, so far, clever.

I keep my prints, an imbroglio,

Fifty in one portfolio.

When somebody tries my claret,

We turn round chairs to the fire,

Chirp over days in a garret,

Chuckle o’er increase of salary,

Taste the good fruits of our leisure,

Talk about pencil and lyre,

And the National Portrait Gallery:

Then I exhibit my treasure.

After we’ve turned over twenty,

And the debt of wonder my crony owes

Is paid to my Marc Antonios,

He stops me—”Festina lentè!

“What’s that sweet thing there, the etching?”

How my waistcoat-strings want stretching,

How my cheeks grow red as tomatos,

How my heart leaps! But hearts, after leaps, ache.

“By the by, you must take, for a keepsake,

“That other, you praised, of Volpato’s.”

The fool! would he try a flight further and say—

He never saw, never before to-day,

What was able to take his breath away,

A face to lose youth for, to occupy age

With the dream of, meet death with,—why, I’ll not engage

But that, half in a rapture and half in a rage,

I should toss him the thing’s self—”‘T is only a duplicate,

“A thing of no value! Take it, I supplicate!”

Before the battle, Perry, not surprisingly, had bet all of his money on himself and when he lost, he became destitute. Thus, as quickly as William Perry entered the world of bare knuckle boxing, he just as quickly left it. He was not the type of man who saved much of his earnings from his boxing career and so he went back to doing various types of manual labor for the remainder of his days.

Twenty-three years later, on December 24, 1880 at his home in Old Tollgat House, Bilston, Perry passed away of pulmonary congestion, attributed to some extent to his alcoholism, at the age of 61.

Perry, who for much of his professional boxing career unmercifully beat people up, in a sense got beat up himself by life.

Editor’s note: William Perry was placed to rest at the cemetery of St. John’s Church in Kates Hill, Dudley. In the 1920s, Perry’s grave was in terrible shape and the acting vicar of the church, Rev. D.H.S. Mould held a charity drive to raise money to repair the champion’s grave. In 1925, a new memorial stone was dedicated to Perry.

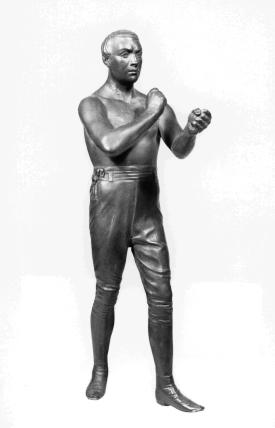

On May 3, 1993, a statue of Perry was erected at the Coronation Gardens in Tipton by artist Bill Haynes. Although the bare knuckle fighter had been dead for nearly 113 years, his legacy was still so popular in the area, that the local residents and town hall all contributed funds to have the bronze statue built. Perry’s remains were later re-interred at the foot of the statue.

The Fountain Inn, where Perry would greet friends and fans alike and hold court, was listed as a Grade II historic site in 1984.

JOHN GULLY

England Boxing Champion

An English Renaissance Man

Story by Mark Weisenmiller

In today’s times, when a Western reader sees the word “Renaissance,” he or she most likely immediately thinks of the Italian Renaissance. Yet renaissance, which is a French word meaning rebirth, can be applied to all sorts of people of all sort of nationalities. One such person is this month’s Bare Knuckle Boxer profile – John Gully of England.

Thorton Wilder, in his classic play “Our Town,” wrote “Wherever you come near the human race, there’s layers of layers of nonsense,” but the good Mr. Wilder obviously had never heard of John Gully, for the Englishman was as sober and straightforward as a minister. His life story is so fantastic, so improbable, that it sounds like the plot of a novel written by his fellow Englishman Charles Dickens.

Gully had the bad luck, or depending on the reader’s beliefs, providence, to have been born (in August 21, 1873 in Wick, Gloucestershire) into a family that was quite poor. His father was a butcher and this is not a vocation that is known for producing many millionaires. The hero of our tale worked alongside his father and when his dad died, young John took over the business. In 1805, the butcher proprietorship collapsed, and as a result Gully was sent to jail for failure to pay debt. Thus Gully was in gaol in the city of Fleet. Both figuratively and literally, Poor John. As English debtor law at the time ordered that a person imprisoned for such could be in gaol for life unless the debt was paid, so it appeared that John Gully would spend the rest of his life behind prison bars. He was only 22 years old when imprisoned.

Lo, reader, Our Hero was spared of such a fate when he was visited by Henry Pearce, a friend who was a champion pugilist of considerable and many skills. When Pearce learned about the above-mentioned law, he talked Gully into participating in an exhibition bout on the Fleet debtor prison grounds. To Pearce’s surprise, he learned that Gully was talented as a pugilist and he learned it the hard way (previous to this, in 1803, Gully had one fight where he defeated Jack Rand). In a rough and tough fight, Gully so impressed Pearce that he arranged to have Gully’s debt paid and this set John free. A match between Gully and Pearce was arranged to be held on July 20, 1805 in London, but it was canceled. Summer came and went, Fall arrived, and thus, finally, so did a professional match between John Gully and Henry Pearce, which took place on October eighth of that year in Hailsham.

What a match it was! For 77 minutes – that is, 64 rounds – the two men participated in a memorable battle royale (to use a French term for a bout that took place before the Duke of Clearance, who later became King William IV). Gully was at first clearly intimidated, for Pearce knocked him down at least once in every one of the match’s first seven rounds. John rejiggered his boxing style and began to dominate his rival. By Round 20, it was reported, “One of Pearce’s eyes was almost swollen shut. The two fighters battled on, both bruised and bleeding.” Gully continued to pound Pearce and it is a testament to the latter that he was able to continue. Finally, in Round 64, Pearce hit Gully with a clean, straight jab to John’s throat. Our Hero immediately had trouble breathing and had to submit and that was, without question, the only reason that Henry Pearce won the match.

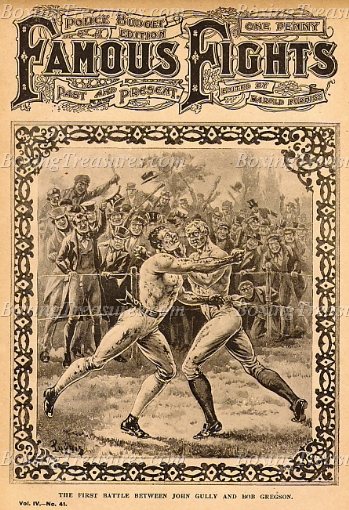

Because of this titanic match, Gully became the recognized boxing champion of England when Pearce had to retire due to ill health. “He proved his ability, when he defeated a Lancastrian rogue named Bob Gregson in front of a crowd that included dukes, marquishes, and lords, at Six Mile Bottom near Newmarket in 1807,” according to Harry Mullan’s 1996 book “The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Boxing: The Definitive Illustrated Guide To World Boxing.” This match, which lasted 36 rounds, was won by Gully; he was now the champion.

Gregson wanted a rematch and so, in May of 1808, when Gully was 35 years old, they fought again in Woburn, England. This time, Gully took 24 rounds to defeat Gregson and then announced his retirement from boxing. Why?

Because, reader, Gully’s heart and soul was never really and truly into The Sweet Science. For this man, boxing was merely a way to get out of the economic doldrums. His first vocation after boxing was becoming the owner/operator of a pub (“The Plough Inn”) and this vocation brought him into contact with the lower depths of English society.

Quickly realizing that he would not get rich running an inn, and also realizing that socializing with said lower depths would probably eventually lead him back to jail, he got involved with the so-called “sport of kings” – horse racing. He began to, as is quoted in his profile in the “Britannica Online Encyclopedia,” place “betting commissions for important patrons, among them the prince regent (later King George IV). In 1827, he lost 40,000 pounds in backing Marmeluke (which he had bought for 4,000 guineas) in the St. Leger (race).”

First, Gully was a book-maker and later he became an owner of horses. Gully, who was a tenacious man before, during, and after his boxing career, continued moving forward in his goal of obtaining a horse that would bring him lucrative purses. After some years, this began to happen. One of his horses, Ugly Buck, won two thousand guineas in 1844. Two more of his horses, Purkhus The First and Mendicant, won, respectively, the Derby and the Oaks races in 1846. Eight years later, two more of his horses, yet won two more notable English races.

Finally, he accumulated a total wealth of 40,000 pounds and now, he believed, was the time to quit the horse business. So he did. Gully took part of his horse industry winnings, built himself a house in Yorkshire, and became a candidate for Parliament in 1832. The extremely popular Gully won his election and for five years, from 1832 to 1837, he was a MP (Member of Parliament) for Pontefract, Yorkshire. Gully could have been re-elected – for he was that rare politician who tried to do his best for his constituency for as long as he could – but he decided to retire from public office.

Gully was twice married and had 12 children by each wife. This made for a grand total of 24 children, so it appeared that John was just as prolific in his personal life as he was in his professional endeavers. He was now rich, so to note, in both.

The former champion used some of his wealth to buy the Wingate coal mines and estate in County Durham and he became a popular and well-liked member of the landed English gentry, so much so that, again, he was the equivalent of a character worthy of a Dickens or (to use another famous English writer as an example) a D.H. Lawrence novel. He was the polar opposite of the stereotypical mean, myopic, cheap English gentry-man. He was kind, considerate, and at least for the time period being discussed, paid his workers moderately decent salaries.

John Gully, the English Renaissance Man, died in Durham, England on March 9, 1863 at the age of 79. For those readers interested in genealogy, Wikipedia records that “his daughter Mary married Thomas Pedley. Their son was engineer and cricketer William Pedley.” This latter Pedley, in turn, brought his engineering skills and talents to the United States (specifically, to California) where eventually he developed the irrigation system that was used in Riverside, California. Thus, in an unusual way, John Gully’s vibrancy continued, even after his death, through his offspring. Thus, reader, our story now ends.

Mike McCoole

The Troubled Champion

Story by Mark Weisenmiller

With this Bare Knuckle Boxer profile, The USA Boxing News now presents one of our occasional biographical sketches of a pugilist who found himself in repeated conflicts with the law. So we may as well get the lowest point of this Ireland-born (specifically, County Donegal) boxer’s life discussed now.

To wit: In October of 1873, McCoole (whose last name is sometimes spelled McCool by boxing historians) – only one month after he lost the Heavyweight Championship of America, in seven rounds (it lasted 20 minutes), to Tom Allen in a match held in Illinois in front of 2,000 fans – had a quarrel with a lightweight boxer named Patsy Manley. The quarrel took place in front of a saloon in St. Louis, Missouri. As is often the case, things became uncivil, at which point McCoole shot Manley with a gun that he (McCoole) had previously concealed. Manley was shot in the left breast, died due to ventilation by way of a lead bullet, and McCoole (who had recently retired from boxing) was arrested by local police.

Convicted in court of murdering Manley, McCoole was then imprisoned. However, in mid-February of 1875, Mike was acquitted on a reason that now seems to defy legal logic: prosecutors could not find a witness who directly saw the crime. Why the prosecution did not make note of this two years earlier when McCoole was convicted of the crime seems peculiar.

Even though he as now a free man, McCoole still did not have an easy life, economically-wise, for not long after he got arrested, his saloon was closed. Whether this was due to his arrest, his loss to the popular boxer Allen, or due to some other matters, people simply stopped fraternizing McCoole’s establishment. Not long after this, McCoole – who was, to use a phrase from his home land of Ireland, “a man who liked his glass,” – started and operated another saloon in St. Louis which was much more successful than his previous one. He died in October of 1886 in New Orleans, Louisiana where, seven years earlier, he had migrated to work, in a variety of jobs, affiliated with that city’s waterfront and shipping industries.

This last point is a key one in the life and times of Mike McCoole. During his boxing career, his nickname was “The Deck Hand Champion of America” and that was due to the fact that he was a lifeong waterfront and/or vessel manual laborer. Whether this was due to fate (after all, he was born on the island nation of Ireland), or circumstances beyond his control is a moot point; the fact remains that he was a man of the seas and waterways of America.

One must always remember that in his day, commerce and travel were done primarily by way of navigation on the United States’ many lakes and rivers. This simple fact is also why the majority of the top American cities, even today, are, to use a phrase, waterway cities.

This last point was true even in McCoole’s day. (He was born on March 13, 1837 and came with his family to New York when young Mike was but 13 years old). Proof of this can be seen by simply looking at the list of some of the cities where he fought his bouts: Chicago, Illinois; Louisville, Kentucky; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York, New York; St. Louis, Missouri. All of these are waterway cities.

Due to his constant troubles with the law enforcement agencies, Mike, still in his teens, left his family back in New York and travelled westward. He ping-ponged between Louisville and Cincinnati, Ohio. Wherever the manual labor jobs for steamboats (which is the first kind of vessel that McCoole worked on) were, that is where McCoole went.

Hauling freight and moving heavy boxes for hours a day made Mike McCoole into a tall (6’2”) and strong (200-pound) man. He was, however, quite clumsy in his physical movements and certainly was not the most graceful of men. Mike had his first fight in April of 1858 in Louisville, against Bill Nary, and finished off his foe in the eighth round.

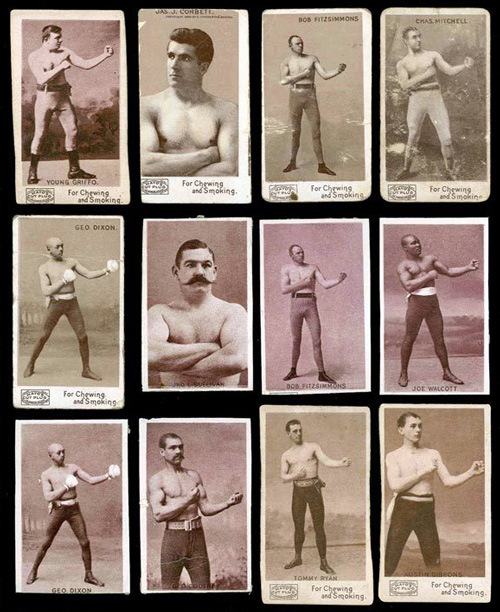

By no means at this stage of his pugilistic career could he be considered a finesse and fundamentally sound boxer. When he fought smaller-in-size opponents, he simply threw them to the floor and such rules were then permitted in bare knuckle boxing in the United States under the Broughton Rules and later the London Prize Rules. Regarding style and substance back then, American bare knuckle boxing was quite primitive and mostly illegal if a prosecutor desired to bring formal and legal charges against the event’s financial backers.

For McCoole, bare knuckle boxing was simply a second job, a way to earn some much needed extra dollars (waterfront manual labor jobs, in these pre-union days, did not bring a man much income). Evidence of this can be seen by examining his boxing career biography, for he only had one fight in 1859 – a battle on Twelve Mile Island off the Ohio River in Louisville, KY on June 29, 1859 where he bludgeoned William Blake in 37 minutes and 29 round – none in 1860, one in 1861 where he pummeled Tom Jennings in 33 minutes on May 2, 1861 in New Orleans, LA for a $500 purse, and one in 1862, although it is not known how many unofficial clandestine battles McCoole may have participated in during the period.

McCoole’s name was becoming more and more well known by bare knuckle boxing fans in the U.S. because he won most of these matches and so, on May 6, 1863 for a purse of $2,000, in a contest in the rural town of Charlestown, Maryland, 30 ft. from the from the shore of the North East River. McCoole fought Joe Coburn for the Heavyweight Championship of America. In a bout that lasted 70 minutes, Coburn stopped McCoole in the 67th round before a crowd of 2,000 fans.

This irked the Irishman McCoole to no end. In October of 1864, he publicly challenged Coburn for a rematch. At this point in Mike McCoole’s pugilistic career, he began to take bare knuckle boxing seriously.

Almost two years later, on September 19, 1866, McCoole beat Bill Davis in a contest at Chouteau Island in Madison County, IL, over 35 rounds. With the win, the brash Irishman began to publicly call himself the Heavyweight Champion of America. Since Coburn had retired from boxing in 1865, and considering that the title was now vacant, McCoole’s claim was justified. For most of McCoole’s fights, he earned $500.

McCoole defended his championship by pummeling English-born Aaron Jones in a match in rural grove in Busenbark’s Station, Ohio on August 31, 1867 before an impressive crowd of 3,500. The bare knuckle boxing fans of the day in general and Mike McCoole in particular, wanted the Irishman to again fight Coburn. This was all set to occur on May 27, 1868 in Cold Springs Station, Indiana. Yet once again in the life of Mike McCoole, problems with the police occurred. The cops in Indiana found out about this fight to be and Coburn was arrested. McCoole was also arrested and both men spent the Fourth of July, 1868 imprisoned in Indiana. This was not McCoole’s first arrest. Earlier in his life, he was arrested in Cincinnati when police there got a tip that he was to fight there. They warned McCoole no to engage in the bout. He ignored thee warnings and was promptly arrested.

How, the reader may ask him or herself, did Mike McCoole find his way to St. Louis? Well, he met and married a Irish colleen named Mollie Norton. Not surprisingly, Mollie – who, by all accounts, was just as fiery an Irish person as Mike – did not put up with his rough-house ways and the marriage was a short-lived union.

The year was now 1869. The American Civil War had ended and the country’s populace east of the Mississippi River was trying to cope with Reconstruction while the country’s populace west of the Mississippi River seemed to be exploding and expanding westward. McCoole and Allen were scheduled to fight in St. Louis and, one day before the bout and, sure enough, local police found out about the bout and arrested both Allen and McCoole. This happened before their 1873 bout, but during their 1869 fight, Allen pummeled Mike without mercy until McCoole won the bout when Allen fouled him.

That wrapped up the life and times of the bare knuckle boxing career of Mike McCoole. As quickly as he came into the world of bare knuckle boxing, he seemed to have left it doubly fast. By the time he died in New Orleans (at only the age of 49) on October 17, 1886 at Charity Hospital, he was long forgotten by the majority of the American bare knuckle boxing fans. Mike McCoole learned the hard way something fundamental about American sporting fans. That is, if you do not win a championship in the sport you are engaged in, and also, more importantly, if you do not stay champion for many years – you are quickly forgotten.

McPoole was buried at St. Patrick’s Cemetery near Canal Street in New Orleans, LA.

Tom Paddock

The Battling Brawler

By MARK WEISENMILLER

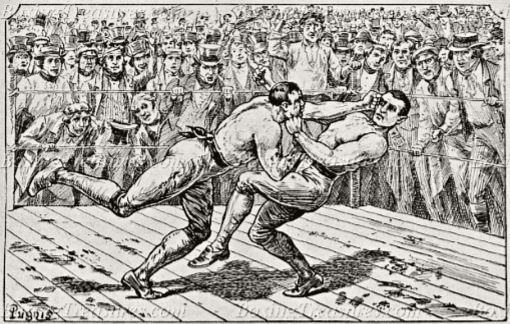

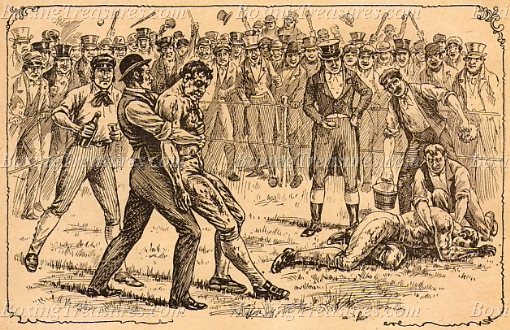

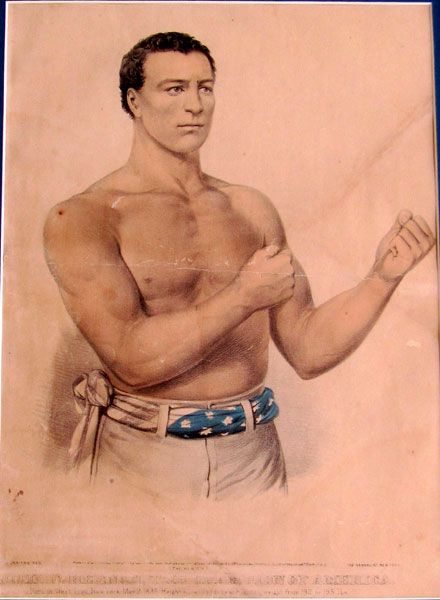

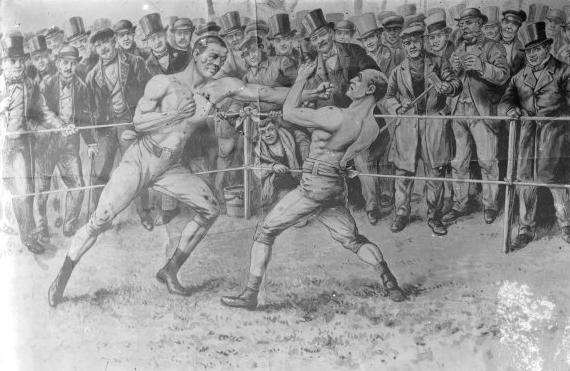

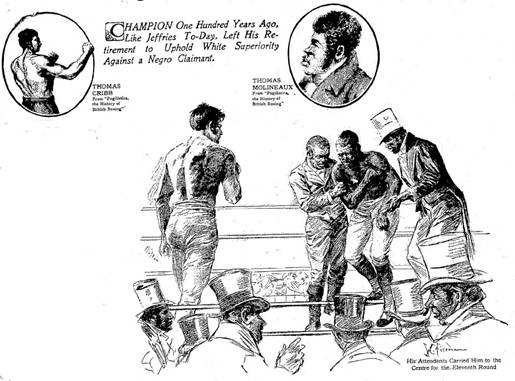

Tom Sayers KO’s Tom Paddock, 1858, June 15th, after 21 rounds to win the English Heavyweight Boxing Championship.

By now, readers of these profiles of bare knuckle boxers written by this author know that the majority of bare knuckle boxers in history were rough and tough brawlers. However, occasionally, we find one such brawler who was such a misanthrope (let’s be honest here; rather, a Cro-Magnon) that it almost amuses us that he had any type of success at all during his days as a boxer. Thus, we now present the case, before the court of boxing fans public opinion, of one Tom Paddock. This man, in his long pugilistic career, had so many matches in which he did just about anything and everything in them except to actually box, that it is a wonder that he was not arrested by British law enforcement authorities on charges of—well, you name it. Actually, Paddock, as we will discover below, once was arrested.

In Paddock’s defense, his boxing bouts (and a valid argument could be made that they even qualify, by today’s standards, as boxing matches) attracted tremendous crowds in their day. Rare was the day when, in a match which pitted two talented pugilists against each other, that such a donnybrook did not attract an audience of at least 20,000 people. Yet, in some ways, this man is a mystery.

Those who read these profiles of bare knuckle boxers in The U.S.A. Boxing News know that in the history of this part of the sport (and this applies not only to bare knuckle boxers in the United Kingdom, but to bare knuckle boxers in other countries as well) that every once in a while there arises, seemingly out of the morning mist, a talented boxer whose background is unknown. He has great success, but nobody seems to know his past. What is his name? Is he using a pseudonym while working as a pugilist? Is he married, and if so, does he and his wife have children? Where was he employed before he became a boxer? What is his past? Does he come from good English stock and breeding (this was a common question asked by boxing fans in the United Kingdom in those days of the white upper class caste system)? Those are but a few of such questions that were then discussed back then by British fans of pugilism.

Tom Paddock was such a person. We do know that he was born in Redditch, Herefordshire in 1824 but do not know his birth day and month. Then, until he had his first major bout at the age of 20—nothing. We do not now what his father did for a living (Herefordshire was primarily an agricultural area and thus the possibility exists that he was a farmer or worked as a farm hand for a local plantation owner). We do not know if Tom had any brothers or sisters (which means that we do not know if he has any descendants). Nothing.

In the afore-mentioned first bout of Paddock’s, he defeated Elijah Parsons in 23 rounds. Two years later, Paddock battled Nobby Clarke for 42 rounds. Less than 18 months later, in a 55 round bout, Paddock again beat Clarke.

By this time Paddock—who was but 5 foot 8 inches and weighed 166 pounds—had earned a reputation among the thousands of British pugilistic fans as a determined fierce competitor whose bouts had a tendency of lasting many, many rounds. Paddock was undefeated until, on June 5, 1850, he lost to a character named Bold Bendigo (which sounds like the name of a Marvel Comics super hero; actually this was a pseudonym for William Thompson, who hailed from an area made famous by the Robin Hood stories: Nottingham). What must have really annoyed Tom about this match is that he was winning the bout until, in Round 49, when he was called for a foul and disqualified. Some boxing historians, specializing in English bare knuckle boxing history, have discovered evidence that, previous to this foul, there existed the very real possibility that Paddock was going to win the championship from the incumbent Bendigo.

When he lost a bout to William Perry, that was held six months after his fisticuffs fiasco with Bendigo, there were charges that Paddock threw the match (i.e., purposefully lost). This happened after 27 rounds.

Every boxer, no matter what weight class they are in, needs an opponent whose pugilistic skills either equal or are slightly better than his own. Such a duel, such a class of characters, traditionally bring out the best and worst of each boxer. In our time, the classic example of all of this was Muhammad Ali against Joe Frazier.

Well, Paddock, at this stage of his career, now met such a foe. He was a man named Harry Poulson. Paddock lost the first of the two boxers three matches, in71 rounds on September 23, 1851, won Bout Number Two in 86 rounds in December of 1852, and won the last match in a bout that lasted—and by today’s standards of boxing, this seems incredible—102 rounds.

Paddock and Poulson took an immediate dislike to each other from their very first meeting with an intensity that can only be compared to when a cat first sees a dog. Frankly, they hated each other intensely, so much so that between bouts two and three, both men served time in goal when they were found guilty, on charges of disturbing the peace, when they got into a fight outside the squared circle and in public.

Paddock was now used to participating in bouts that lasted numerous rounds. For him, a match that lasted 20 rounds was equivalent to one lasting ten rounds for a lesser man and boxer (and by this time, Paddock was nationally recognized for his pugilistic skills). Thus, his next two major matches, both against Aaron Jones, and which lasted, respectively, 121 and 61 rounds, were mere work-outs for Paddock. It was clear that Tom Paddock was simply too talented to never win a championship.

On May 19, 1856, he got his chance against Henry Broome. In a bout that lasted 63 minutes (that is, 51 rounds), Paddock won. Tom Paddock, 32, was, at long last a champion.

With a new champion came a newly created championship belt and then the worst thing possible that could have happened to Paddock, regarding his championship, occurred: his success went to his head. He spent less and less time practicing his pugilistic skills and more and more time becoming a sloth. So, in a match on June 16, 1858, it was not surprisingly that he lost when he defended his new championship belt against Tom Sayers.

Paddock lost the match, in 21 rounds, and slightly over five years later (on June 30, 1863), he died.

Jem Belcher : the Natural

By Mark Weisenmiller

There are some people in life who have a single talent at doing something that the rest of us can not do. Famed American fiction writer Bernard Malamud, in a novel that he published in 1952 about the great fictional hitter Roy Hobbs, created a term for such a personality with the title of said book: “The Natural.” Whether it be mastering French cooking (Jacques Pepin), or being an artist (Pablo Picasso), or virtually single-handedly creating a social movement (Rachel Carson, who is generally credited with starting the environmental movement with her classic 1962 non-fiction book “silent Spring”), such people and their unique talents inevitably become popular.

Such a person, in his day, was Jem Belcher. What makes this remarkable is that he was barely 19 when he defeated a pugilist (Jack Bartholomew, who claimed to be champion; back then, in early 19th century England, often the roughest and most bawdy of men of questionable boxing talents, boisterously proclaimed themselves to be champions) and died at the young age of 30 (in July of 1811). Yet, in his time, he was so appreciated by boxing fans that he was called the “Napoleon of the Ring.” Like the famed French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte, Belcher was short, temperamental, multi-talented, and had a personality filled with numerous peccadilloes which led him to make insipid choices in his life. Unfortunately, due to what we would now consider the primitiveness of work historian then in general, and boxing historians in particular, today we have no idea how many fights Belcher participated in which means, of course, that we have absolutely no idea how many he won and how many he lost.

Jem Belcher was born in Bristol, England on April 15 (some boxing reference books and sources state April 25), 1781 and, if the old adage that a person is consciously or subconsciously influenced by where he or she is born and raised holds true, then Belcher would be a good example. Bristol was (and still is) one of the major international ports of Europe; it has extensive docking facilities at three separate locations. Thus, due to natural geography, Bristol is a transportation hub, trading center, and financial center.

Flour milling, printing, and the manufacturing of footwear (i.e., boots and shoes), paper, and tobacco products are done here. Centuries-old cathedrals also still exist. By the time that Belcher was born and grew up in Bristol, total business trade in the area’s ports had somewhat declined due to the fact that British colonial trade—which was powered by slavery—was nil due to the work on behalf of slaves by local Quakers.

All of this is mentioned because much of it, either directly or indirectly, affected the life of Jem Belcher (not, of course, all of it; there were no traces of the existence back then of the French-British supersonic liner known as the Concorde which was built in Bristol in the last third section of the 20th century). The rough-and-tumble everyday way of life in a large dock town; the temptation to ruin by mindlessly drinking and wasting away life in pubs; the large segment of society that were humorless and pious Christians (some would describe them as zealots) and who tried to convert the heathen (and make no mistake, there were plenty of heathen in those days)—all of this helped to form and shape young Jem Belcher.

Bristol then was known as a city which produced many talented pugilists; in addition to Belcher’s brother Tom, other champions in the early days of British boxing came from the port town (so did, incidentally, long-time film star Cary Grant, who started life there under his real name of Archibald Leach). Belcher—who at 5’ 11” and 166 pounds would now today probably be considered a middleweight—was the grandson of former English heavyweight champion Jack Slack. The boyish-looking Belcher (boyish-looking that is, until alcoholism ravaged both his face and his body) had agility, speed, and (for his weight class) surprisingly strong punching power. He was also intelligent in the fact that after he won his first notable bout—in Bristol and against Jack Britton; the March 16, 1798 donnybrook lasted all of 33 minutes—he made it a point of only fighting when absolutely need be. Most pugilists of the time fought as often, and for as long as possible in matches, both to win, but more importantly (in their estimation) to earn as many British currency pounds as possible.

Almost one month after this match—to be more precise, on April 15, 1799 in a bout held in the picturesquely named Wormwood Springs, England—he defeated Paddington Jones (another lyrical name ! ) in a bout that also lasted 33 minutes. Belcher—who as time passed grew more and more confident of his boxing abilities—decided to take on Bartholomew. The match, held in Uxbridge and which is now known as the Greater London borough of Hillingdon, lasted 51 rounds. This must have been exhausting for both pugilists as well as those who attended and decided to stay the entire bout. In the end Bartholomew won but, more importantly to Belcher, he discovered that he could (figuratively speaking) stand toe to toe with the champion. Belcher very much wanted a rematch and on May 15, 1800 in Finchley, he again battled Bartholomew.

This time, Jem was ready. Thoroughly dominating the champion, he easily won the match (which lasted 17 rounds) and the only reason that it lasted that long was due to the fact that Bartholomew was defending his championship. Jem became champion, to reiterate, at the tender age of 19. To paraphrase a famous line used in both the 1932 and 1983 film versions of the movie titled “Scarface,” the world was his. However, the boxing gods had a different fate in store for the “Napoleon of the Ring”—as we shall soon see.