PRIMO CARNERA – His Heavyweight Legend Lives On

PRIMO CARNERA – His Heavyweight Legend Lives On

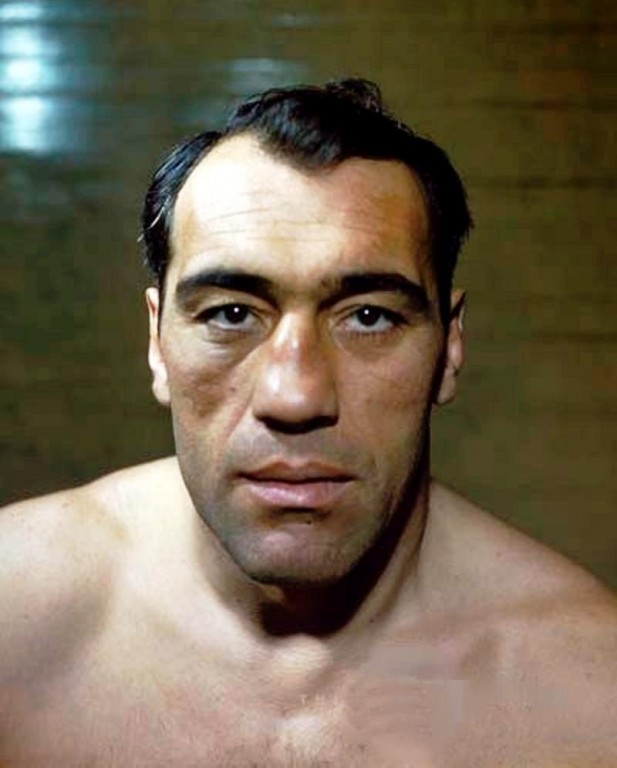

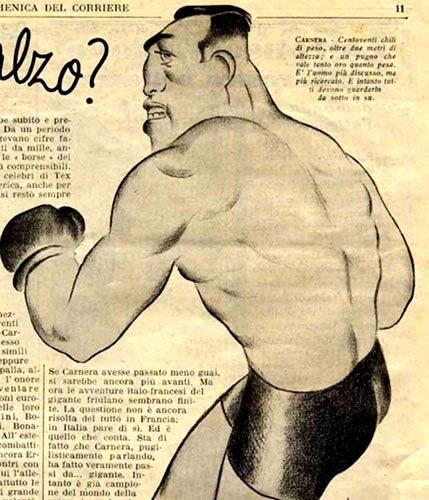

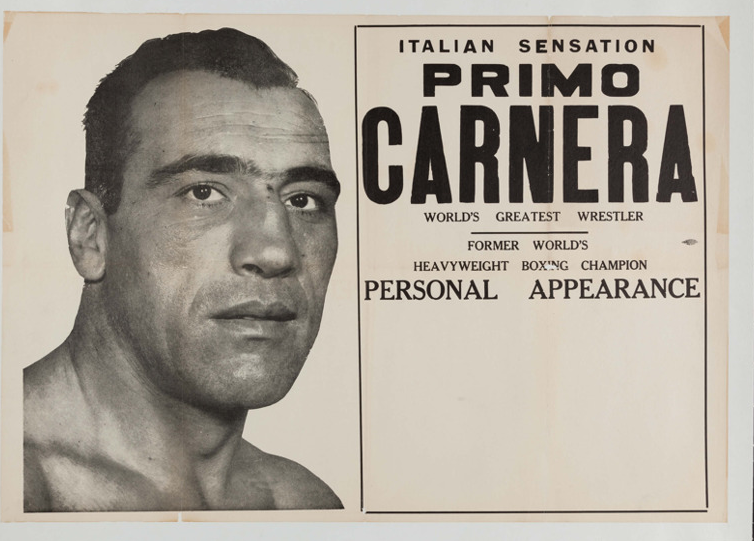

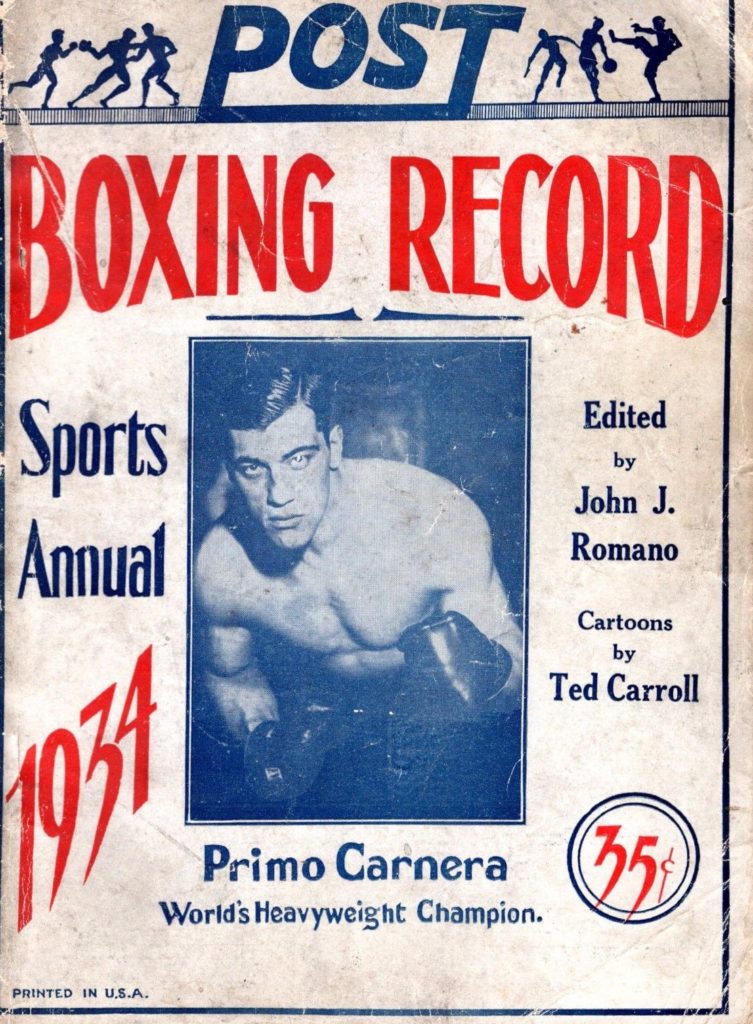

Primo “The Ambling Alp” Carnera

The Legendary Giant King of the Heavyweights

Story by John Rinaldi and Alex Rinaldi

“To be great is to be misunderstood.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson – “Self Reliance,” Essays: First Series (1941).

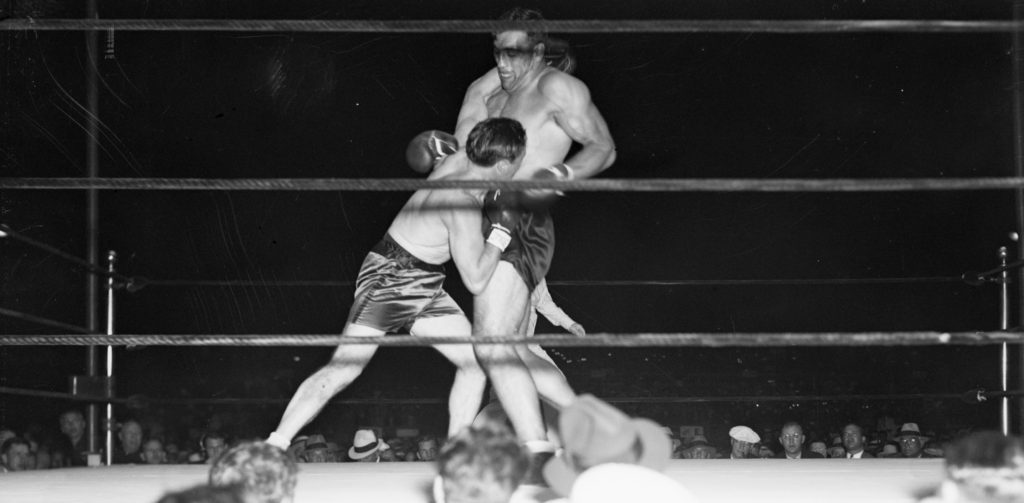

It has been over 85 years ago, when one devastating, ripping right uppercut on a summer night on June 29, 1933 put a giant of a man and his country smack in the annals of boxing history.

That was all it took when the Italian underdog Primo Carnera captured the world of sports’ biggest prize when he knocked out heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey in Round 6 in front of a crowd of 40,000 at the Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island City, Queens, New York.

Virtually overnight, Primo became the hero of Italy, a position he still holds some 51 years after his death. In addition to his native homeland, he was also idolized among the Italian neighborhoods throughout the United States, including one in Massachusetts named Brockton, where future heavyweight champion and fistic immortal Rocky Marciano lived and came to look at Carnera as one of his earliest heroes.

“When Carnera won the title, there were celebrations everywhere,” Marciano once said. “He gave every Italian a sense of pride and hope.”

It is a tragic shame that because of an overrated movie and severely prejudiced sportswriters, Carnera’s great name has been unjustly maligned and his wonderful accomplishments clouded over the course of decades.

The malevolent and blatantly false stories written about Carnera’s career are exactly what Fake News is about today.

One thing The USA Boxing News prides itself on is righting the wrongs and clearing the truth pathways in boxing history, and there was no greater wrong than the slanderous accusations slinged at Primo Carnera during and after his lifetime.

The query which is often made is whether Primo Carnera was a great fighter. Opinions aside, we feel that his terrific record sufficiently speaks for itself.

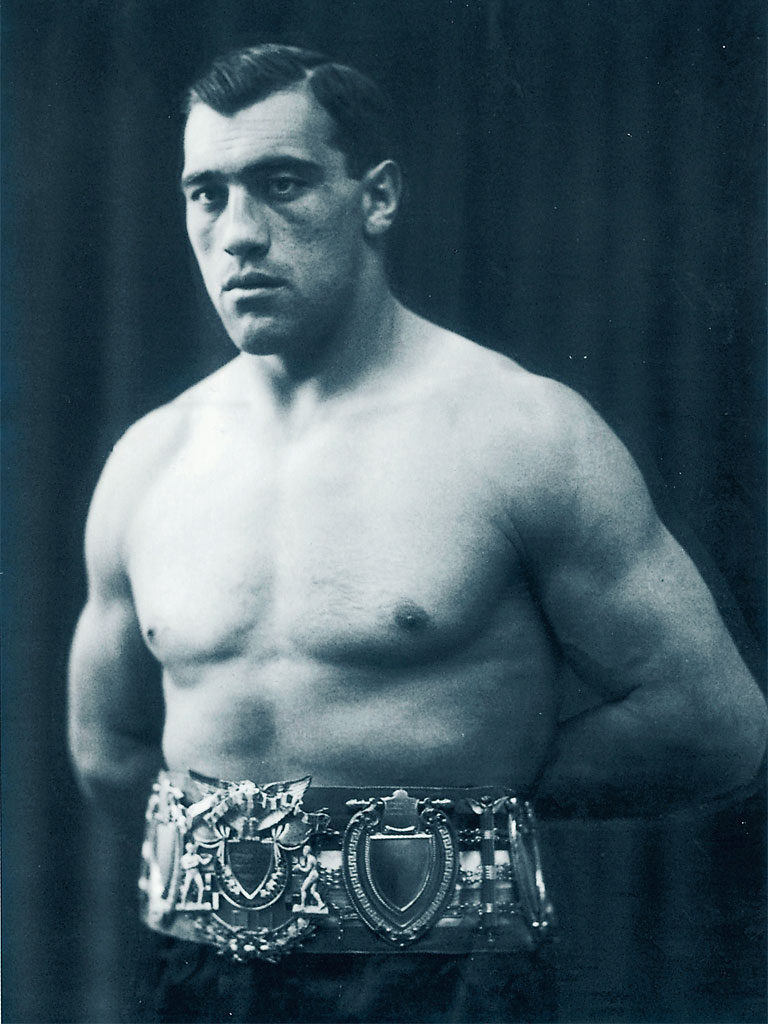

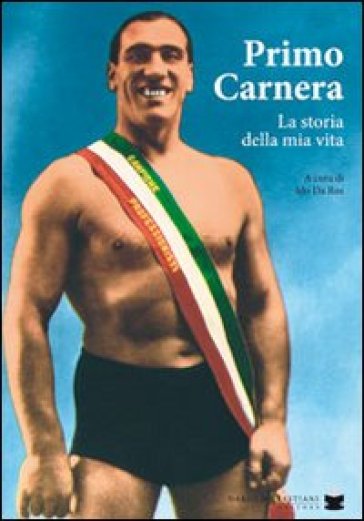

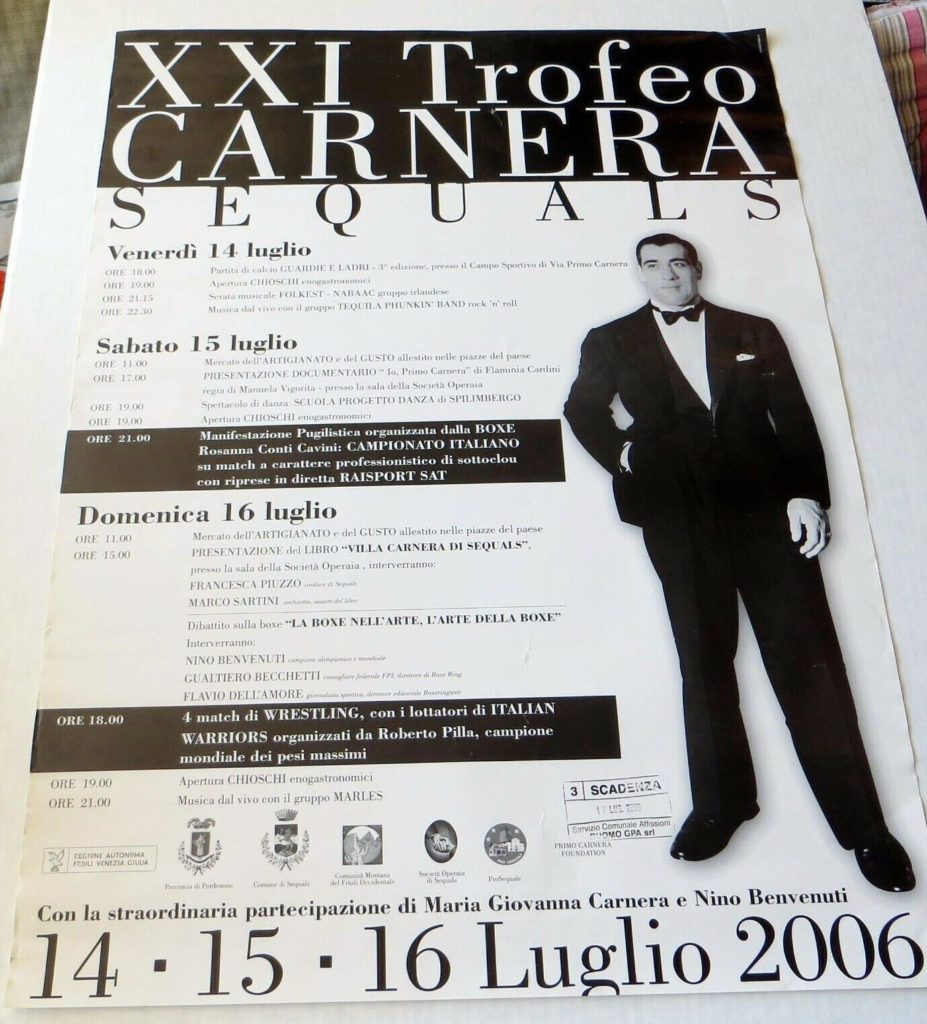

Primo Carnera wearing his EBU Heavyweight Title Belt. (click photo to view Primo Carnera vs Reggie Meen (1930) fight)

From 1928 to 1937, and then from 1945 to 1946 (following the Second World War), Carnera compiled a majestic record of 88-14-1 ND (71 KOs), 3 of those defeats coming in his last three bouts when he was nearly 40 and spent time in the Second World War. No matter how one rolls the numbers, the truth is that it is a sensational record.

Remember, this was in the era when fighters fought almost every other week. In 1930, for example, Primo engaged in an astonishing 26 fights – winning all but one of them, and scoring 23 knockouts in the process!

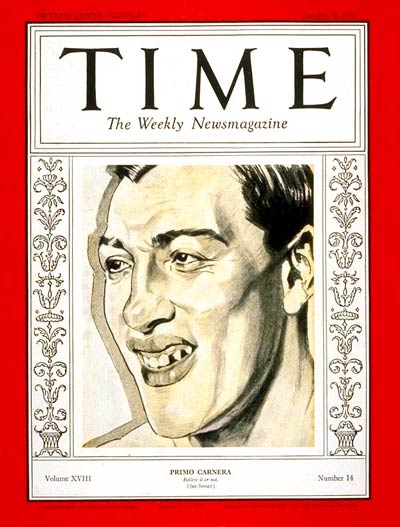

Primo Carnera on the cover of Time Magazine on October 5, 1931. (CLICK PHOTO to view Primo Carnera vs Paulino Uzcudun II fight)

Sadly, due to the poison pens of the usual venomous drunkards masquerading as writers in the United States after Carnera’s career was already over, who either harbored an ethnic prejudice or just plain wanted to push the limits of their imagination for some fanciful reading, somehow the legitimacy of Primo’s victories have come into question over the past 70 years.

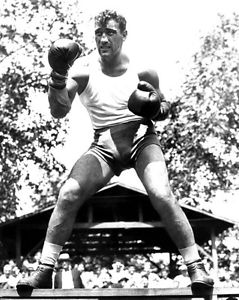

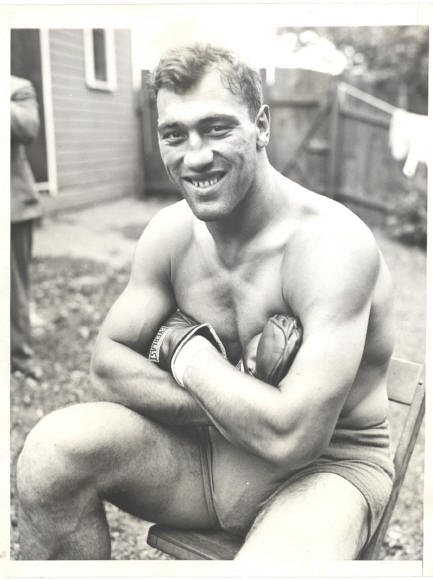

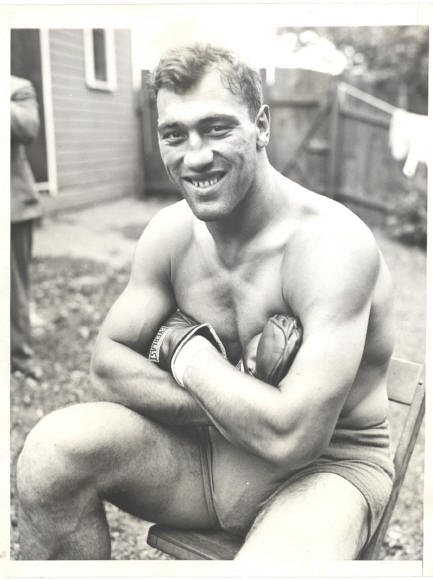

Primo Carnera relaxing during training. (CLICK PHOTO to view highlights of his bout against Tommy Loughran)

Considering the fact that most of those writers who compose such Grimm Fairy Tales never saw Carnera fight live, and that there is not one shred of evidence to support such heinous allegations, the falsehoods have incredibly been listed as fistic facts over the decades. Because of that, Carnera’s rightful place in history has been unjustly compromised.

After years of strenuous research and investigation, including conversations with fellow fighters Jack Dempsey (the former heavyweight champion, who was ringside at all of Carnera’s big fights), Johnny Risko (top-ten heavyweight contender from 1925-1930), Allie Stolz (2-time lightweight title challenger), Max Schmeling (former heavyweight champion and live witness of many of Carnera’s United States and European fights), the immortal Henry Armstrong (the only man to hold three titles simultaneously – featherweight, lightweight and welterweight championships) and former heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, along with various cornermen and others involved in the sport of boxing at the time, who were still alive, we have come to the conclusion that Carnera’s victories were not only legitimate, but that he was one of the greatest heavyweight champions who ever laced on a pair of gloves.

All one has to do is look at the RING magazine’s ratings that were compiled at the time, not the ones that were drastically altered in a monstrous opportunity to rewrite history, and the name of Primo Carnera was listed as a top-ten heavyweight in 1929 (#9), 1930 (#4), 1931 (#3), 1932 (#4), and as heavyweight champion in 1933. Subsequent to losing the title in 1934 to the legendary Max Baer, he was still ranked in 1934 (#2) and 1935 (#3). Therefore, for seven straight years, Carnera was a major force to be reckoned with in heavyweight division, as well as one of the top-ten heavyweights in the world. Plus, the great Nat Fleischer, who was the editor/publisher of the RING, was also a well-respected boxing judge and referee, and his integrity was certainly beyond reproach. Moreover, he clearly recognized real talent, and he firmly believed that Primo Carnera was one such talent. That, in and of itself, surely justifies the legitimacy of Primo Carnera’s boxing career. The only “accusations” that ever came to light were from former jilted manager Leon See, a man who was unceremoniously discharged by Carnera’s handlers in 1931 and surely had an ax the size of Paul Bunyan’s to grind, especially when he missed out on the gravy train years that followed.

The only “accusations” that ever came to light were from former jilted manager Leon See, a man who was unceremoniously discharged by Carnera’s handlers in 1931 and surely had an ax the size of Paul Bunyan’s to grind, especially when he missed out on the gravy train years that followed.

What Carnera built his record on in the early part of his career is still standard fare today. He traveled across the world in all sizes of cities, villages, hamlets and small towns and faced many type of fighters. Granted, some may not have been as talented as Primo, but part of the reason to take on such type of foes is to learn some skills, boost one’s confidence, work on different boxing techniques and styles, stay in fighting condition, and to build up a record. The reason the giant Italian won all of those fights was that he was a special kind of fighter who combined an immense style, with extraordinary quickness, speed and power to put away most of his early opponents in quick succession. It was as a result of those wins that eventually gave Carnera the confidence, skill, and drive to punch his way to the heavyweight championship.

During the 1930s, America and most of the world, was involved in the greatest Depression since the Irish potato famines of the 1800s. Many men who could not obtain employment eventually ventured into the boxing gyms to gain money, fame and fortune. Never before, or since, were there so many guys who slapped on boxing mitts, thereby, making the time period from 1929-1941, the most competitive era in the history of boxing. Considering that there were only eight weight classes, with most having only one recognized title holder, the competition was fierce, to say the least. It was out of this phenomenal competition that Primo Carnera emerged to become one of the most popular and dominant fighters of his era.

It was out of this phenomenal competition that Primo Carnera emerged to become one of the most popular and dominant fighters of his era.

Carnera EARNED his shot at a world title by beating not just one, but eight top-ten contenders such as George Godfrey, Vittorio Campolo, Paulino Uzcudun, Young Stribling, Ernie Schaaf, King Levinsky, Don McCorkindale and Jim Maloney. It would be ludicrous to believe that during the Great Depression a contender would risk a chance at an extremely lucrative world title opportunity by taking a dive. That is just pure, fanciful Hollywood fiction.

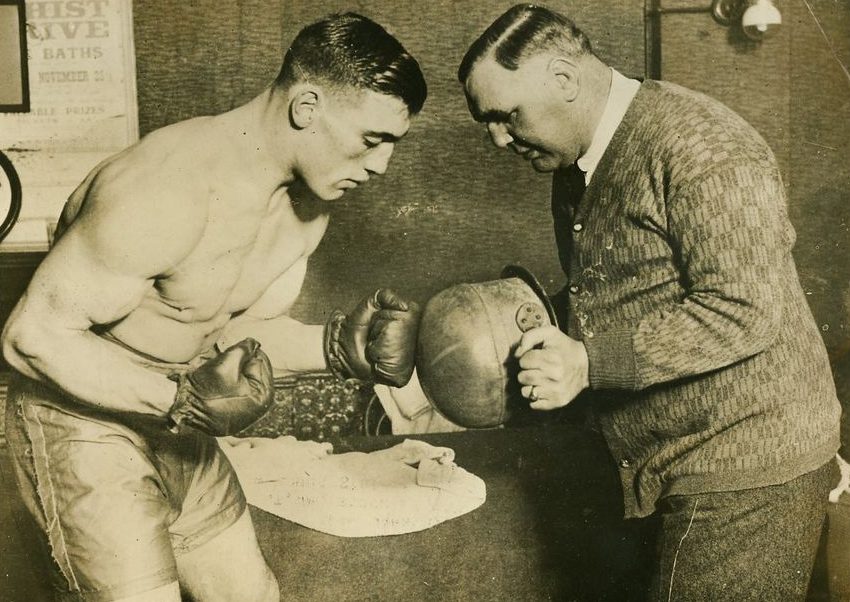

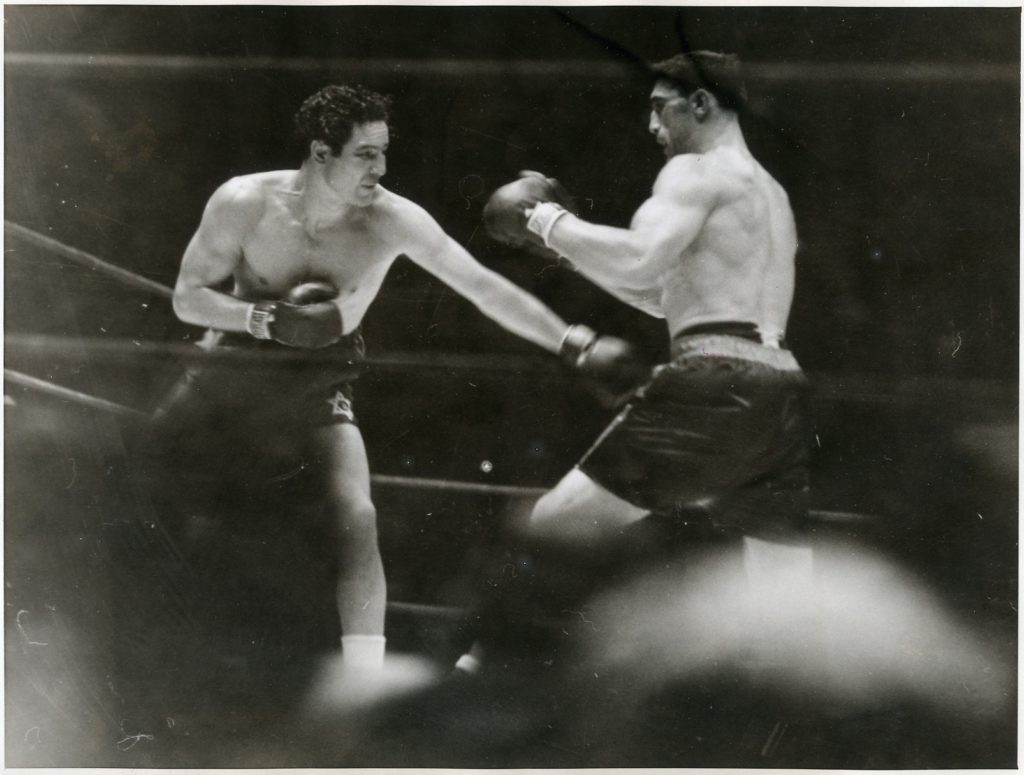

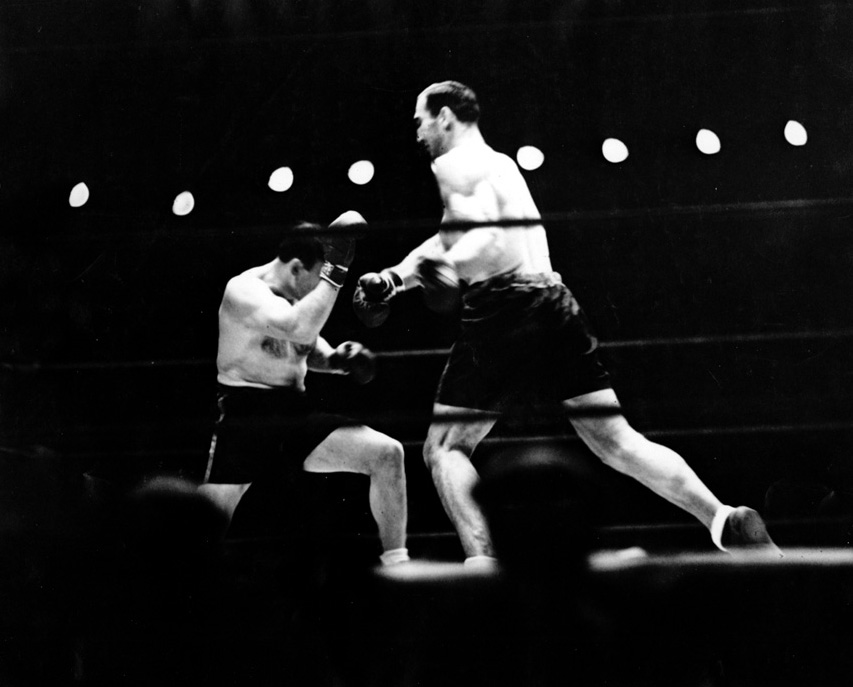

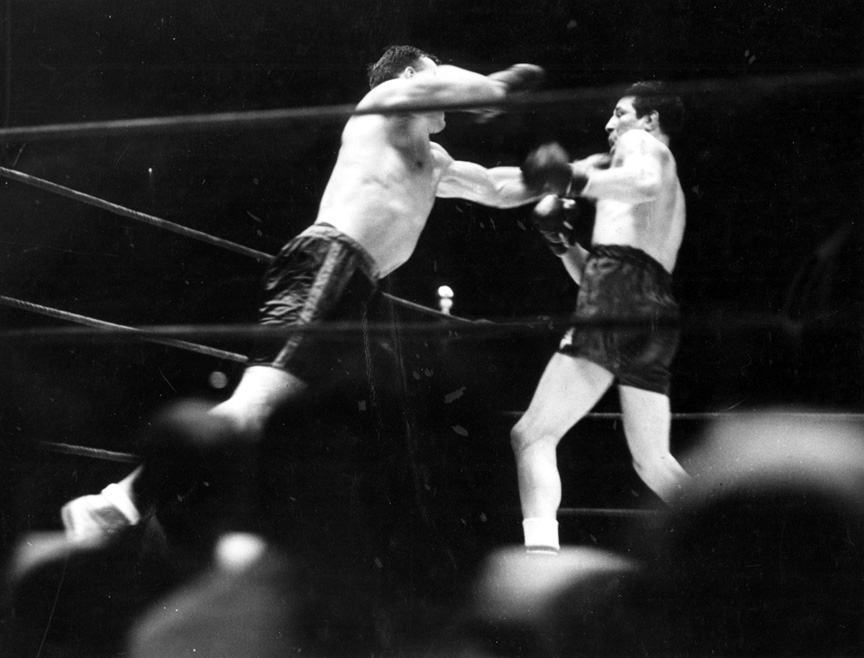

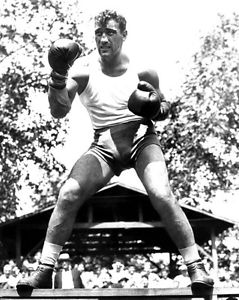

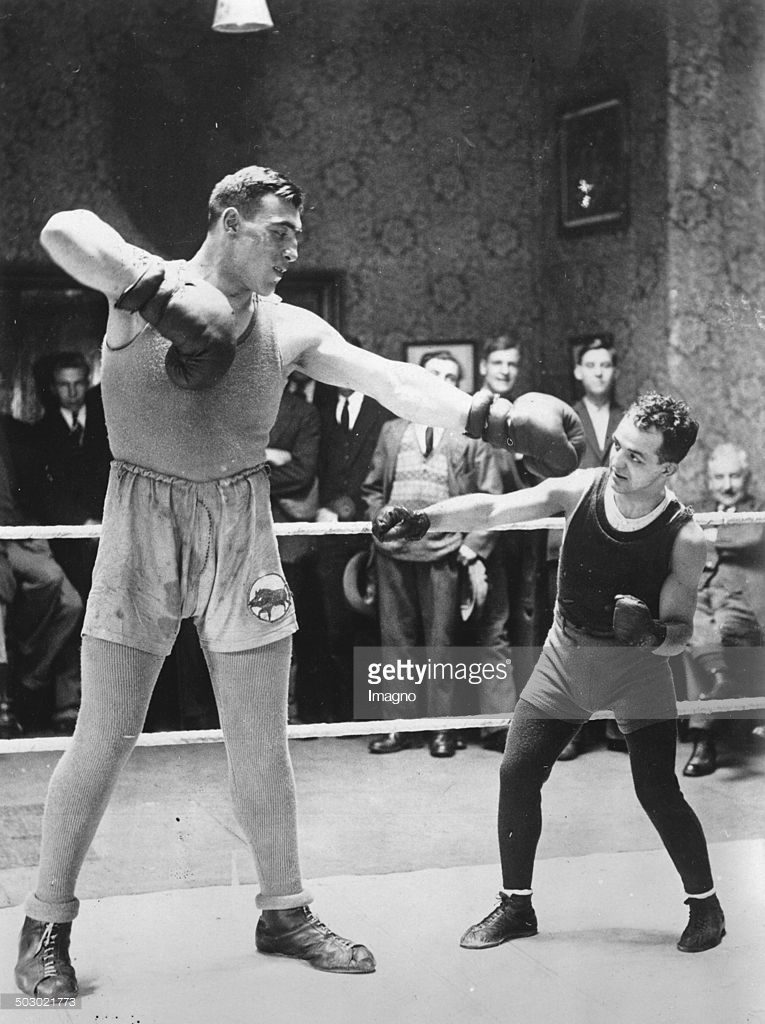

Primo Carnera and Tommy Loughran slug it ouT. (CLICK ON PHOTO TO VIEW INTERVIEW OF CARNERA BEFORE THE FIGHT)

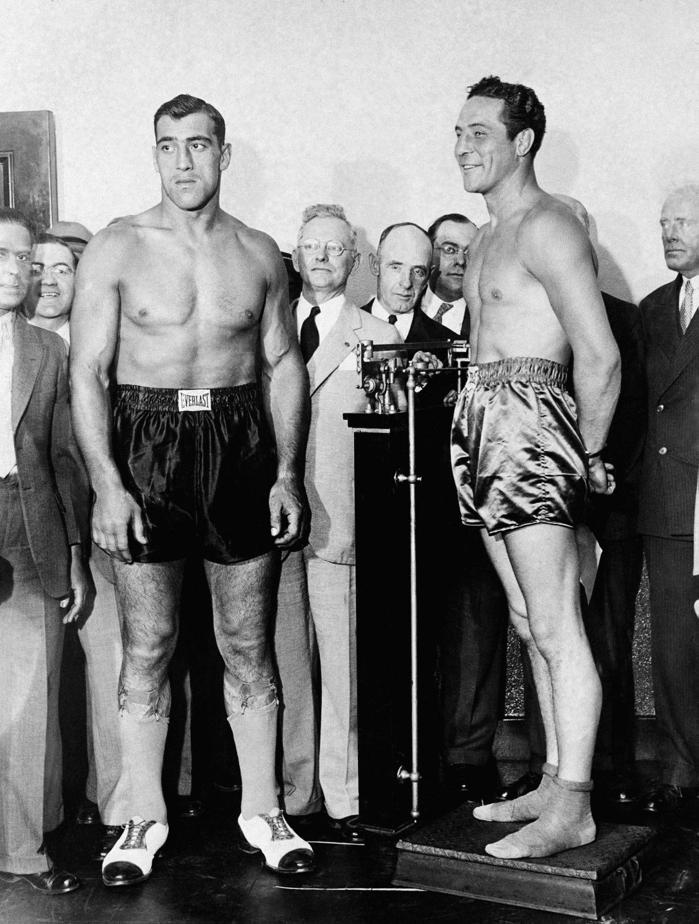

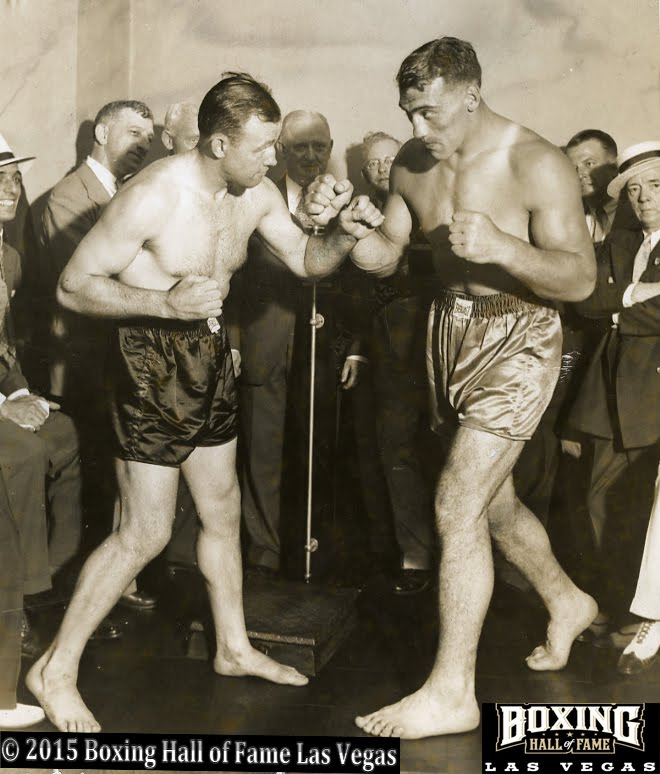

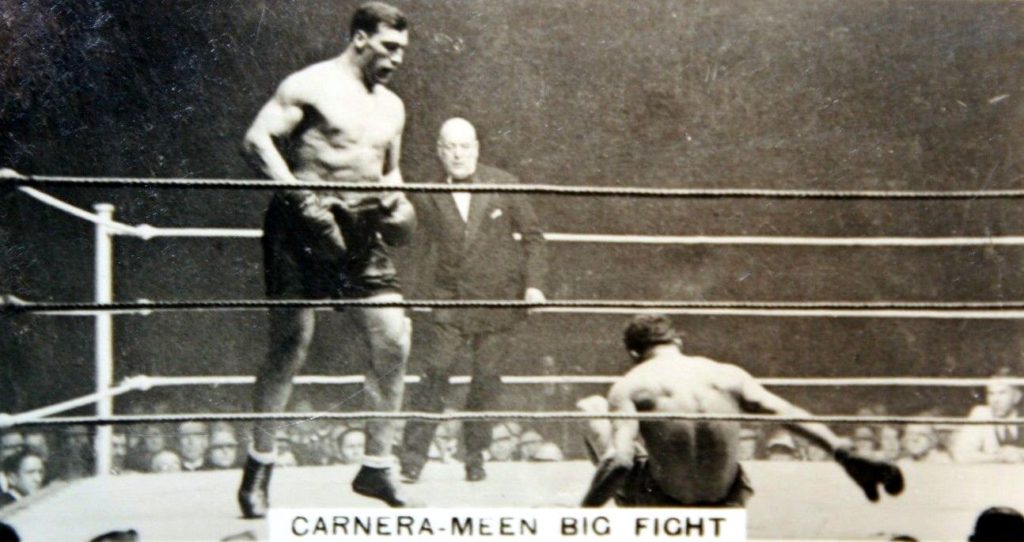

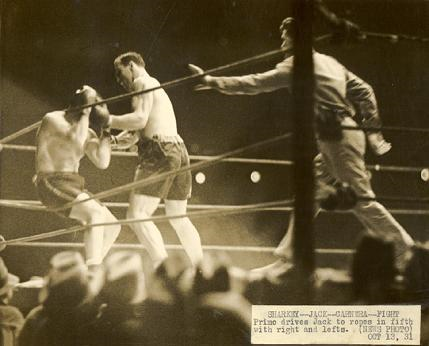

Besides being one of the top heavyweights on the planet for seven straight years, Carnera was also one of the sport’s biggest draws. His first big fight came on November 30, 1930 when he captured a 10-round split decision over Paulino Uzcudun over ten rounds before 75,000 fans at the Estradio Olimpico de Montjuic, in Barcelona, Catalufana, Spain. The win thus made Carnera the EBU – European Heavyweight Champion. On October 12, 1931, Primo faced future heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, who had been a top-ten heavyweight contender since 1924 and had given the immortal Jack Dempsey a tough going in 1927 before being KO’d in the sixth round. On June 12, 1930, Sharkey was defeated by Max Schmeling on a disputed 4th-round foul for the vacant heavyweight championship. Sharkey had won the first three rounds and in Round 4, Schmeling went down to the canvas on a borderline low blow and was unable, or unwilling, to get up. Referee Jim Crowley promptly disqualified Sharkey. At the time of his fight against Carnera, “The Boston Gob” was the top-ranked heavyweight contender.

On October 12, 1931, Primo faced future heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, who had been a top-ten heavyweight contender since 1924 and had given the immortal Jack Dempsey a tough going in 1927 before being KO’d in the sixth round. On June 12, 1930, Sharkey was defeated by Max Schmeling on a disputed 4th-round foul for the vacant heavyweight championship. Sharkey had won the first three rounds and in Round 4, Schmeling went down to the canvas on a borderline low blow and was unable, or unwilling, to get up. Referee Jim Crowley promptly disqualified Sharkey. At the time of his fight against Carnera, “The Boston Gob” was the top-ranked heavyweight contender. Carnera’s first meeting against Sharkey took place before 30,000 fans at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Sharkey proved to be too experienced and dropped Carnera with a left hook in the fourth round. Primo rose and battled back gallantly, only to lose a 15-round unanimous decision. After the fight, Sharkey told Carnera, “You’re a hell of a sight better than I thought – and plenty game.”

Carnera’s first meeting against Sharkey took place before 30,000 fans at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Sharkey proved to be too experienced and dropped Carnera with a left hook in the fourth round. Primo rose and battled back gallantly, only to lose a 15-round unanimous decision. After the fight, Sharkey told Carnera, “You’re a hell of a sight better than I thought – and plenty game.”

Primo learned from that fight and proceeded to go on a tear as he won 26 of his next 28 fights, scoring 20 knockouts over the next 14 months before he was matched against Ernie Schaaf, the 5th ranked heavyweight contender on February 10, 1933 at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

The Carnera-Schaaf bout was scheduled for 15 rounds and was considered a title elimination fight with the winner being matched with heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, who had recently defeated Max Schmeling in their rematch on a controversial 15-round split decision win on June 24, 1932. A sold-out crowd of 18,000 turned out to see the heavyweight battle.

Ticket for Primo’s championship bout with Paulino Uzcudun. CLICK PHOTO TO SEE VIDEOS OF BOTH FIGHTS)

Against Schaaf, 207, Primo repeatedly stabbed his opponent with his powerful right hand and battered Ernie with jolting rights and lefts. Carnera, 250, was in control of the bout and late in the fight, the blows from his giant foe had taken their toll as Schaaf was clearly hurting.

At the sound of the bell for Round 13, Ernie barely got off his stool and came out wobbling. Carnera went after him and soon lashed out with a quick left jab that smashed into the face of Schaaf and sent him crashing to the canvas where he was counted out at 0:51 of the thirteenth round.

Sadly, Schaaf never regained consciousness and was immediately taken to the Polyclinic Hospital where he underwent an operation in an effort to relieve the pressure on his brain by removing a blood clot. The surgery failed to help the injured fighter and he tragically died four days later. The doctors at the time theorized that the death could have been caused by Carnera’s punches, or that Ernie may have had some cyst, lesion or tumor. Also considered was that Schaaf had recently been battling influenza days leading up the contest, and may have been in a weakened condition, something that was dangerous against a fighter of Carnera’s caliber and punching power.

Years later, many have blamed Max Baer for causing the damage to Schaaf in their bout and that Ernie was like a “dead man walking” at the time the bell rang to begin his fight against Carnera. Those prevaricators of the press would make their readers believe that Schaaf fought Carnera days after the Baer contest.

As usual, the TRUTH is far different that the urban legend that has been taken as fact. What actually happened was that Max Baer first faced Ernie Schaaf on December 19, 1930 at Madison Square Garden, and after ten rounds, Ernie was awarded the win via a unanimous decision. The two met again on August 31, 1932 at Chicago Stadium and the rematch was a thrilling affair. It was a close bout leading up the tenth and final round when Baer came out gunning for a knockout. The desperate Baer landed a walloping right hand that floored Schaaf with only two seconds remaining in the fight. The bell rang while Ernie was still on the ring floor, where his corner helped him up, and Schaaf appeared to have recovered when the decision was announced that Baer had won on a 10-round majority decision. Max had to win the tenth round to capture the victory.

So then what became of Ernie Schaaf after the second Baer fight? Well, less than two months later he fought the 10th ranked heavyweight contender Unknown Winston on October 30, 1932 at the Boston Arena, where he lost a razor-thin 10-round split decision. Only 53 days later at the Boston Garden on December 12, 1932, Schaaf got his revenge and KO’d Winston in the sixth round.

That was not all for Schaaf. Ernie then climbed through the ropes 25 days later at Madison Square Garden on January 6, 1933 and TKO’d the #3 ranked heavyweight contender Stanley Poreda in six rounds.

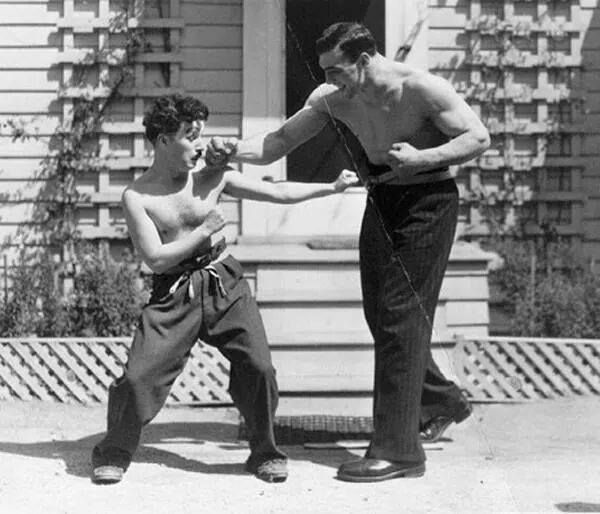

Charlie Chaplin and Primo Carnera (CLICK PHOTO to view Primo “Man Mountain” Carnera vs. Ray “Skyscarper” Impelletiere March 16, 1935)

So Schaaf’s so-called “fatal beating” at the fists of Max Baer is nothing but pure fiction. Between the Baer fight and the Carnera bout, Schaaf fought three more bouts and went 2-1 and scored 2 knockouts. That certainly is not the performance of an injured fighter. On top of that, Schaaf fought legitimate contenders, not a trio of tomato cans.

Regardless, whatever the cause of his death, he Carnera-Schaaf fight is just one of those awful tragedies that sometimes happen in boxing.

Though Carnera was evidently heartbroken afterwards, the win actually earned him a shot against heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, who was such a good friend of Schaaf’s that he even worked his corner against Carnera. Never one to mince words, Sharkey wanted to get revenge on Carnera and since he already had defeated the Italian behemoth, he figured in the rematch, with the World’s Heavyweight Championship at stake, he planned on handing him another sound beating and a much worse bludgeoning at that.

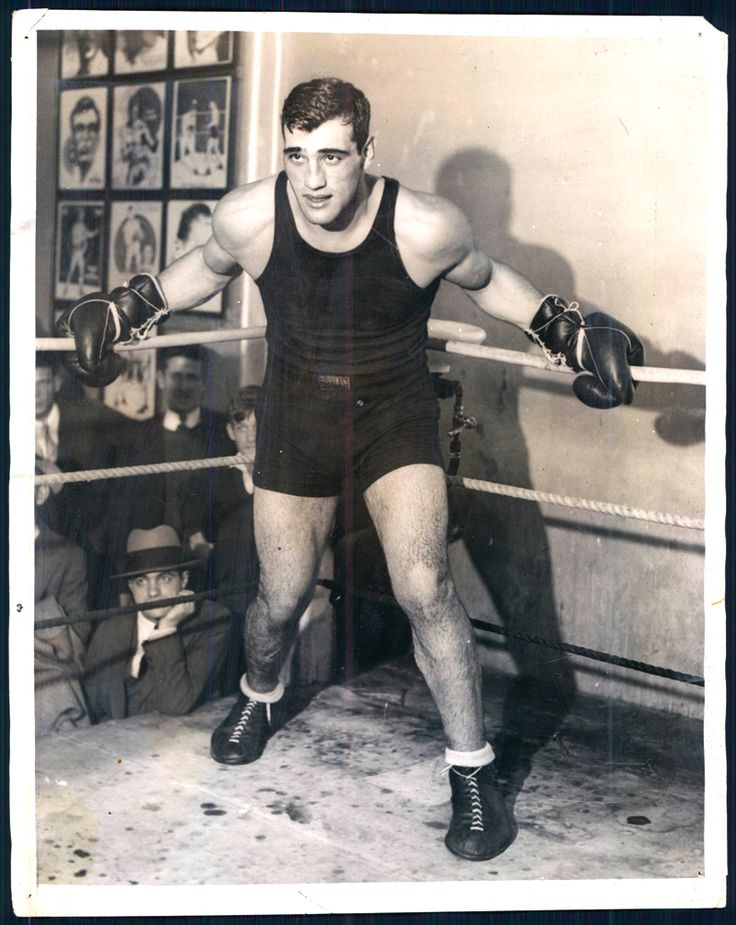

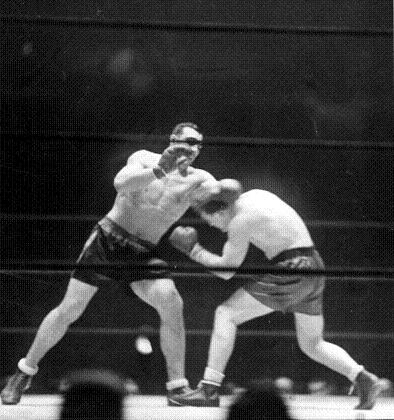

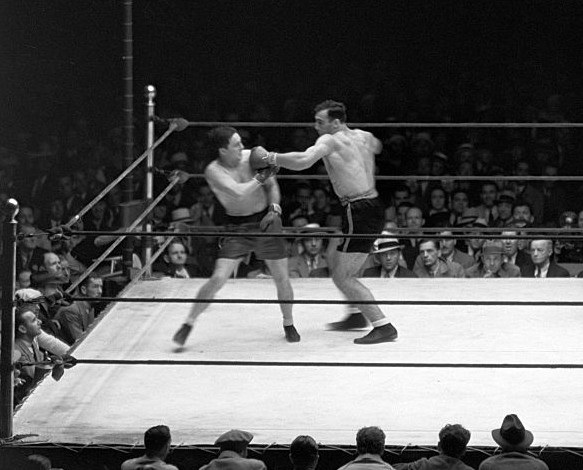

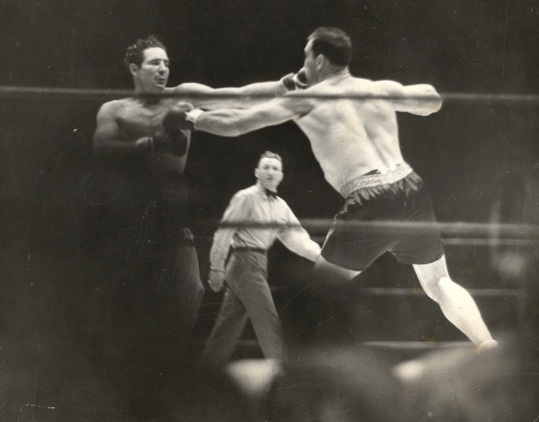

Primo Carnera (R) and Max Baer (L) trade hard jabs. (CLICK ON PHOTO SEE SEE VIDEO OF THE FIGHTERS IN TRAINING FOR THE FIGHT)

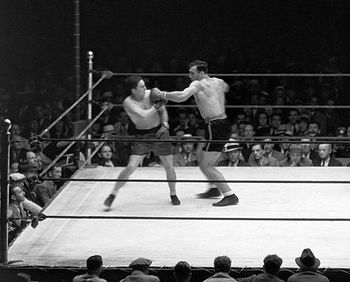

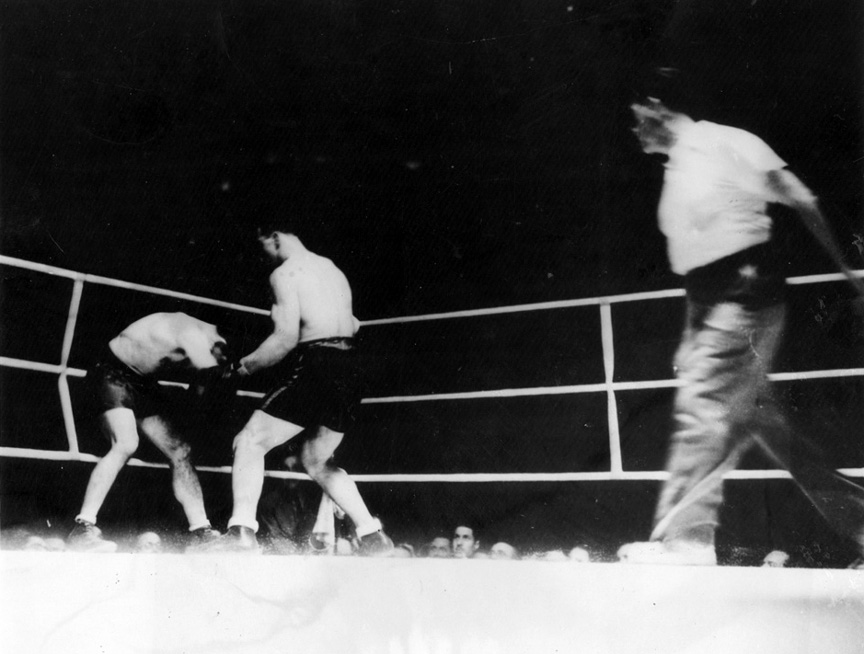

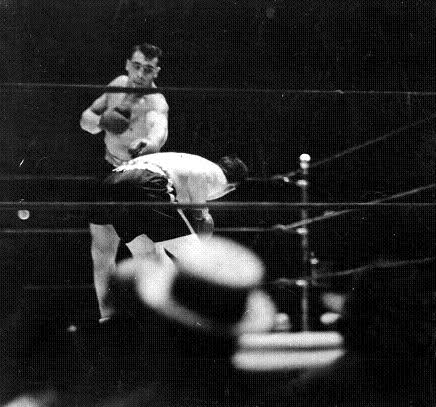

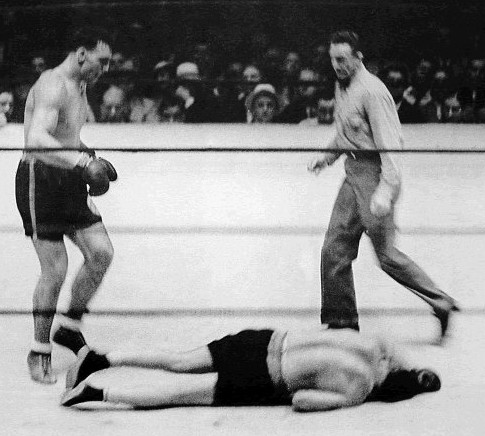

Sharkey, therefore, agreed to defend his laurels on June 29, 1933 at the Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island City, Queens, New York. A large crowd of 40,000 turned out to see the anticipated rematch. The betting odds began with Sharkey as a 5-4 favorite. On the day of the fight, Carnera was the 6-5 favorite, but right before the bell rang, the bookmakers slated Sharkey as the 7-5 favorite.

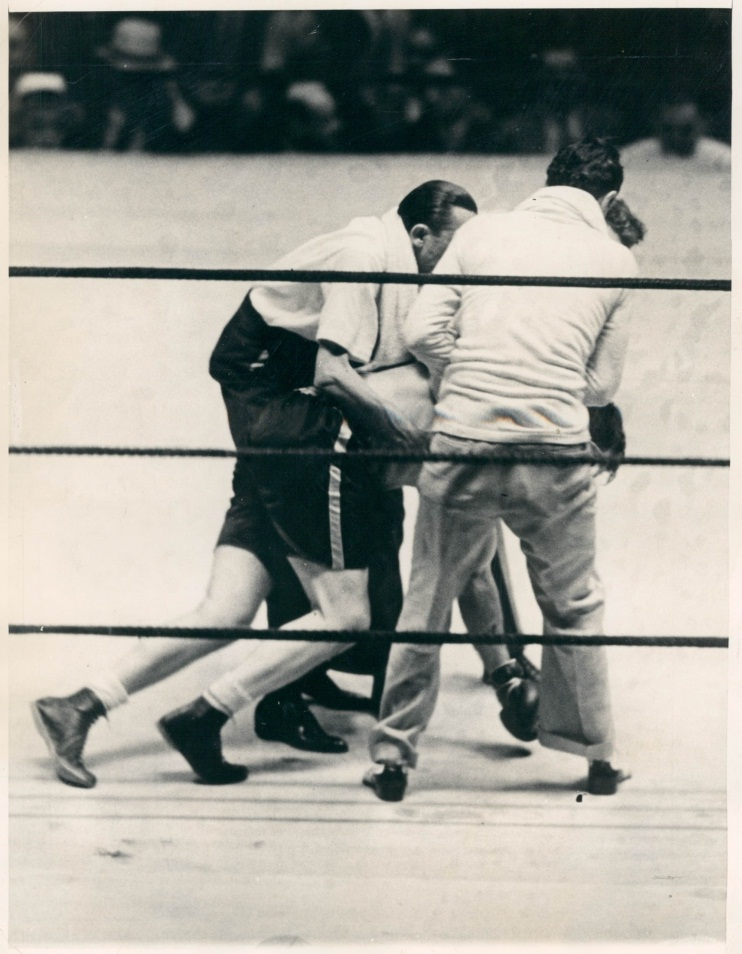

Unlike in their first bout, the first five rounds of the scheduled 15-rounder saw a savage slugfest as Sharkey, 201, traded terrific blows with Carnera, 260 ½. Then in the sixth round, Primo rushed the champion into the ropes and lashed out with both fists pumping. Suddenly, Carnera fired a terrific right uppercut that exploded onto the chin of Sharkey and sent him down and out on the ring floor where he was counted out by referee Arthur Donovan at 2:27 of Round 6. Sharkey was still so nearly unconscious that his handlers had to literally drag him back to his corner and hoist him on his stool until he could clear his head!

For his title-winning effort, Carnera earned $16,377.28.

If one would watch the film of the fight, it was a vicious right uppercut that landed right on the button that finished off Sharkey.

Unlike what was later written, there was absolutely NO controversy with the legitimacy of the knockout punch. All the officials on hand from the New York Athletic Commission were certain the punch was a powerful wallop, along with the Hall of Fame referee Arthur Donovan. Others who were ringside that assessed to the genuineness of the blow were such luminaries as the Ring editor/publisher Nat Fleischer, along with fistic greats Gene Tunney, Jack Dempsey and Max Baer. All of the leading journalists at ringside also saw no question of the knockout, and they included such literary legends as Damon Runyon, Westbrook Pegler and Frank Wallace.

Following the loss, Jack Sharkey said, “Am I going to hang up my gloves? No, I’m not. I’m going to fight again in a couple of weeks, when I’m not so rusty. That’s what is wrong with me now. I have given Carnera two chances and I feel he should give me a chance.”

The beating Sharkey took in the Carnera fight sufficiently finished him off as a big-time fighter, as he went 2-4-1 before he retired after being KO’d in three rounds by ring terror Joe Louis on August 18, 1936.

For those who would think that a heavyweight champion can be paid enough to take a dive while the world was buried deep in the Depression is laughable. In his defense against Carnera, Jack Sharkey earned $69,603.44. In that time period, no athlete earned as much as a heavyweight champion. Besides boxing champions, Major League Baseball had the next highest salaries.  To show the disparity to what Sharkey earned in just one fight, in Major League Baseball the highest earners were: 1933 – Babe Ruth ($52,000), 1934 – Babe Ruth ($35,000), 1935 – Lou Gehrig ($31,000) and 1936 – Mickey Cochrane ($36,000). A heavyweight champion earned even more with public appearances and endorsements. Once a heavyweight king’s title reign was over, the amount of his purses and outside revenue would often and sorely plummet.

To show the disparity to what Sharkey earned in just one fight, in Major League Baseball the highest earners were: 1933 – Babe Ruth ($52,000), 1934 – Babe Ruth ($35,000), 1935 – Lou Gehrig ($31,000) and 1936 – Mickey Cochrane ($36,000). A heavyweight champion earned even more with public appearances and endorsements. Once a heavyweight king’s title reign was over, the amount of his purses and outside revenue would often and sorely plummet.

Also in the deep throes of the Great Depression in 1933, the average household salary was a mere $1,550.00 per year!

In Sharkey’s next fight, which was a loss to King Levinsky on September 18, 1933, the former champion earned $25,000. There was just too much at stake to lose a World Heavyweight Championship, which was the most valuable title in all of sports at the time.

Years later, when the vultures of the press descended upon Sharkey as they attempted to offer their loathing revision of history that he had taken a dive, the former champion explained, “I’d never have done anything like that. I was raised Catholic. I was raised to be honest. I was on top of the world. Why would I purposefully lose?”

Why indeed. It just not make any sense for him to do so.

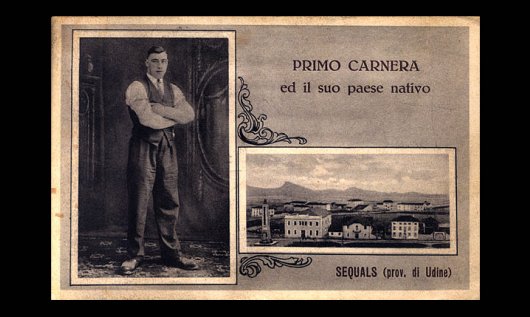

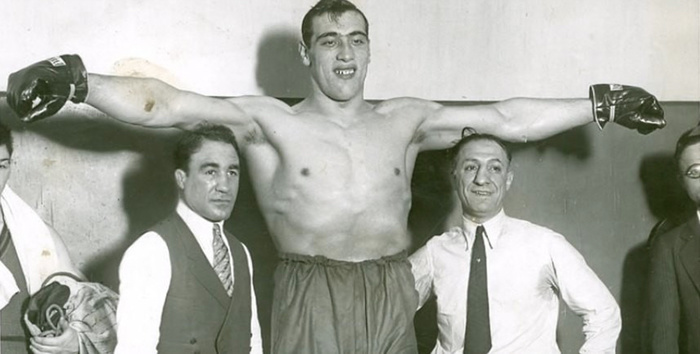

The fact that Primo Carnera came from Sequals, a small village in Northern Italy, to eventually capture the World’s Heavyweight title, was nothing short of remarkable. In the ring after scoring the knockout over Sharkey, Carnera said, “I will fight Baer. I fight anybody. I whip all of them. You’ll see. Primo is champ!”

The new champion, it would turn out, would be a man of his word.

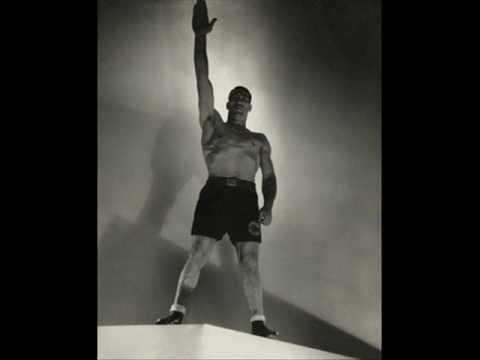

Once Carnera won the title, he set out be the most active and fighting heavyweight champion not seen since the days of yesteryear and the reigns of Jack Johnson and Tommy Burns.

Less than four months after capturing World Title honors, Carnera, 265 ¼, defended his laurels for the first time against contender Paulino Uzcudun, 202 ½, on October 22, 1933 before an audience of 70,000 at the Piazza di Siena, in Roma, Lazio, Italy. Carnera entered the ring a national hero as he captured a 15-round unanimous decision. According to the Associated Press, they wrote, “Carnera gave Uzcudun an unmerciful beating and won every round.”

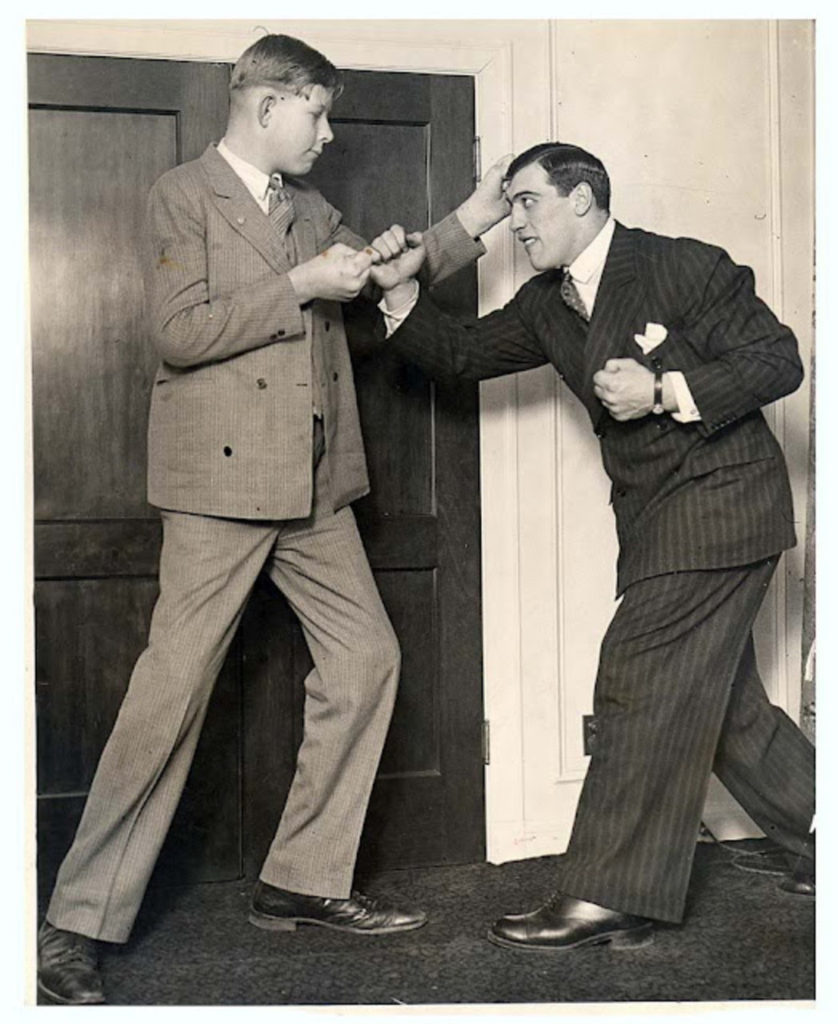

Two real life giants – 12 year old Robert Wadlow with Primo Carnera (CLICK ON PHOTO TO SEE PRIMO FIGHTING SCHAAF)

Next on Carnera’s list was the former legendary light heavyweight champion and #2-ranked heavyweight contender Tommy Loughran. Loughran was a fearsome force to be reckoned with, having defeated top-ranked contenders Steve Hamas, King Levinsky, Ernie Schaaf, Tuffy Griffiths, Vittorio Campolo, Johnny Risko and Stanley Poredo, along with victories over former heavyweight king Jack Sharkey and future heavyweight champions James J. Braddock and Max Baer. To most experts to this day, Loughran is considered one of the greatest fighters to ever lace on a pair of leather gloves. Tommy was slick and crafty and a dangerous opponent to take on, especially if one is defending his heavyweight crown.

Carnera showed no such timidity and faced Loughran on March 1, 1934 at the Madison Square Garden Stadium in Miami, FL, before 15,000 fans. Although Loughran had beaten such top boxers, Carnera was held in such high regard that he entered the ring a 5-1 favorite.

The sharp boxing challenger soon discovered that he was out of his league as Carnera gave Loughran the worst drubbing of his career as he easily won a unanimous 15-round decision by round scores of 10-1-4 (twice) and 12-3.

As usual after taking a terrible pounding in the ring, Loughran was never the same again following his defeat at the massive fists of Primo as evidenced by the fact that after the bout he racked up a mediocre record of 12-8-5 until he retired in 1937.

Now that he had beaten the #2 ranked heavyweight contender in Loughran, Carnera signed on the take on the devastating #1 ranked heavyweight ring killer – Max Baer only three months later!

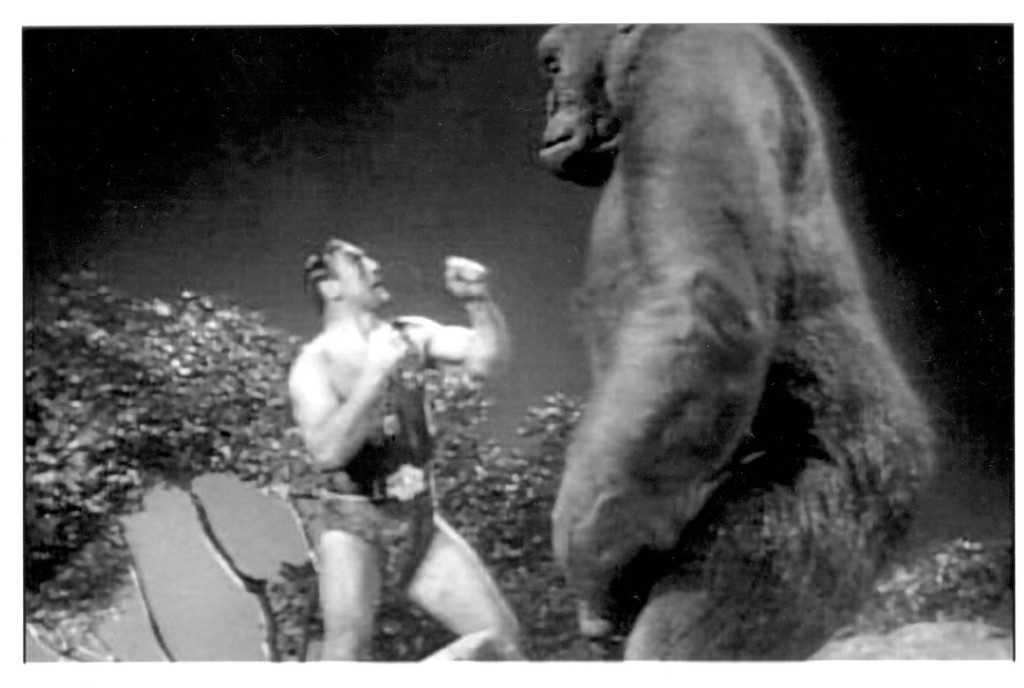

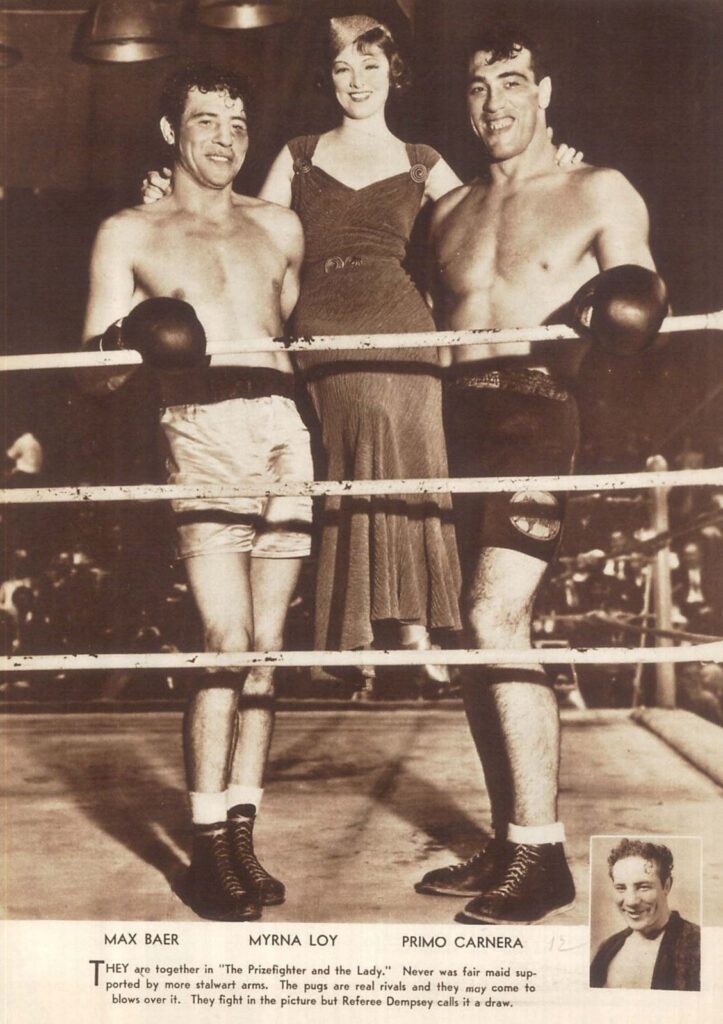

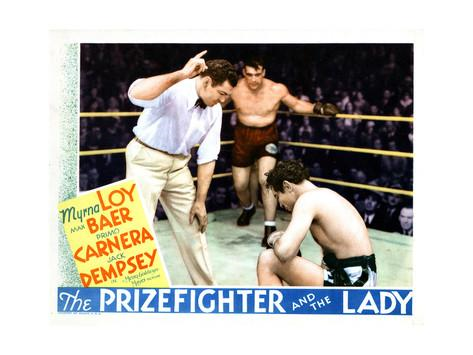

Before the fight with Max Baer, Carnera starred with Baer, along with Jack Dempsey and movie star Myrna Loy in the MGM film, “The Prizefighter and the Lady” that was released to theaters on November 10, 1933.

In the film, Carnera played himself – the Heavyweight Champion of the World. The original script had an ending where Max Baer’s character, Steve Morgan, would knock out Carnera. The champion, however, refused to perform in the movie, so the screenwriters adjusted the ending and Carnera was given an additional $10,000. Both Baer and Carnera made their film debuts in the movie. Years later Myrna Loy, who played Baer’s love interest in the film said, “Max [Baer] carefully watched Primo Carnera’s boxing style during the filming and used this information to beat Carnera in their real-life title fight.”

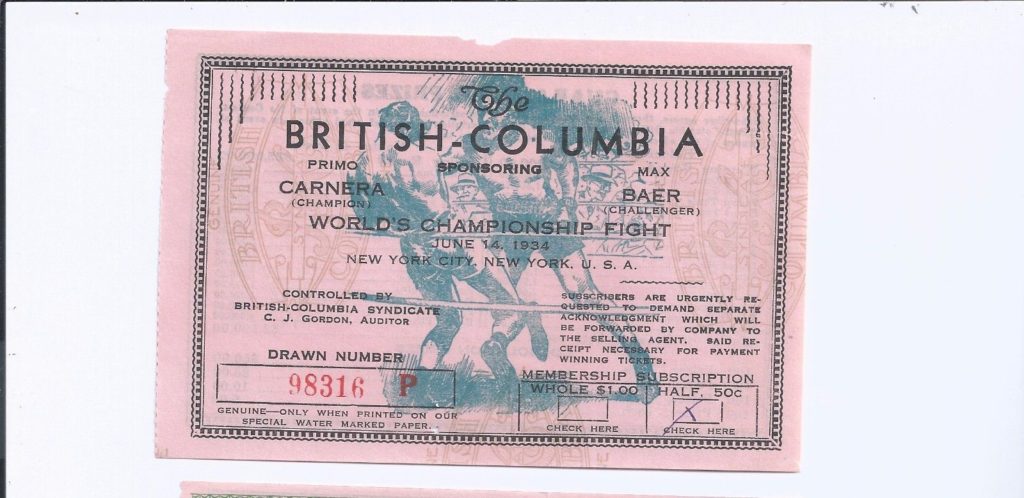

A crowd of 52,268 turned out at the Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island City, NY on June 14, 1934 to see Primo Carnera, 263 ¼, defend his heavyweight title against the terrifying Max Baer, 209 ½, who, in his last fight the previous June 8, 1933, demolished former heavyweight champion Max Schmeling in Yankee Stadium.

As a result of the Schmeling slaughter, Baer was considered virtually unbeatable at the time and was in his boxing prime as he entered the ring against Carnera a 7-5 favorite. After dropping Carnera 11 times, referee Arthur Donovan finally stopped the fight at 2:16 of Round 11, although Carnera was not counted out and bravely kept on getting up.

What is not generally known is that Carnera severely injured his ankle when he was briefly dropped for the first time in the opening frame. From then on, the gallant champion fought the remainder of the fight in excruciating pain. Because of the injury, Primo had trouble with his legwork, and was, therefore, a sitting duck for the mighty overhand right swings of Baer.

Miraculously, Carnera not only valiantly rose without a count from each knockdown, he fought back through many of Max’s clowning and fouling tactics to take control of the fight from the sixth round on.

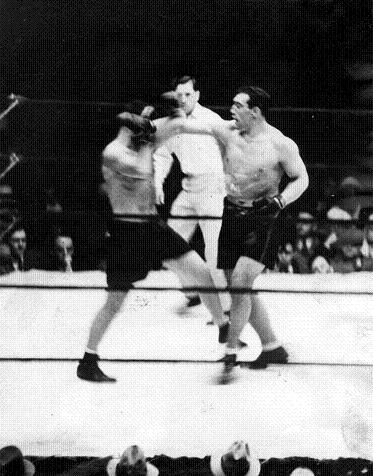

Carnera knocking out Jack Sharkey for the heavyweight title. (CLICK ON PHOTO TO SEE VIDEO OF THE FIGHT)

Unfortunately, the ankle injury had Carnera moving like a peg-legged sailor. By the tenth round, Primo could no longer avoid the challenger’s deadly power punches.

In the eleventh round, the bout was halted when Carnera was down for the eleventh time, even though he had easily beaten referee Donovan’s count. The gross gate of the fight was $428,392.80, with Carnera earning $122,057.20 and Baer pocketing $65,044.31.

The gross gate of the fight was $428,392.80, with Carnera earning $122,057.20 and Baer pocketing $65,044.31.

Another fallacy about Carnera was that “the mob” that controlled him took all of his money. That is patently untrue. Carnera took his earnings and built himself the largest home in his hometown of Sequals, which is today an Italian Sports Hall of Fame.

There are those modern-day “historians” and “experts” who say that Carnera was a “protected” fighter run by “gangsters” at the time. Well, if he was so “protected” why didn’t his managers have him milk the title and defend against lower-tier fighters, just as Gene Tunney did after the second Jack Dempsey fight when he avoided the leading contender Jack Sharkey and, instead, chose to take on the lower ranked and far less dangerous Tom Heeney.

Carnera never took this path of fighting lightly regarded challengers. On the contrary, he defended his title against three ranked heavyweight contenders, particularly #2 ranked Tommy Loughran and #1 ranked Max Baer, two fighters who would probably be champions today. It does not take a village idiot to figure out that Carnera’s handlers had confidence in their fighter, otherwise they could have had Primo take a year off and make a fortune with personal appearances, radio shows, vaudeville tours and other lucrative opportunities that are available to a heavyweight champion all over the globe. Carnera could have also chosen to face a plethora of stumblebums and journeymen to prolong his championship. Remember, there were no boxing organizations then requiring a champion to defend his laurels against the #1 ranked contender, or risk being stripped of his belt. In Carnera’s time, a champion could have defended his title against his sparring partners and not get relieved of his title.

Following the loss to Baer, Carnera was bravely back in the ring six months later and outboxed contender Vittorio Campolo over 12 rounds at the Club Atletico Independiente, in Avellaneda, Buenos Aires, Argentina on December 1, 1934. Primo then knocked out his next three opponents, including another top-ten contender Ray Impelletiere at Madison Square Garden, before he was matched with future legend Joe “The Brown Bomber” Louis.

Louis had entered the professional ranks in 1934 and had won 19 straight fights, scoring 17 devastating knockouts in the process. It got to the point that fighters were actually afraid to even step into the ring with the young 21 year-old ring assassin.

Carnera was not one of them.

On June 26, 1935, four days shy of his 29th birthday, Primo climbed into the ring at Yankee Stadium. It was the biggest fight in years as 64,000 fans showed up to see how the youngster with dynamite in both fists could handle the veteran former champion.

Since Carnera was the bigger draw at the time, he received $86,792.54, while Louis earned $44,636.16.

Unlike all of his previous opponents, Louis, 196, found that he could not finish Carnera 260 ½, off as fast as his previous foes. Louis was tagged repeatedly by Primo’s sharp jab and crunching right hands. Joe shook off the punches and blasted away to the former champ’s head and body with blows that would have destroyed most fighters. Carnera not only took the shots well, but outboxed Louis in the fourth round with blistering combinations.

Although he put up a great battle, few in history could slug it out with the ring terror Louis for long and Joe knocked Carnera down three times in the sixth round before referee Arthur Donovan stopped the bout at 2:32 of Round 6. Once again, against a mighty slugger, Primo was not counted out.

The technical knockout loss at the hands of Joe Louis was surely no disgrace, considering that Carnera was past his prime (Primo turned pro way back in 1928), and in that same time span, Louis knocked out fellow heavyweight champions Max Baer, James J. Braddock and Jack Sharkey.

The Louis fight was another example that Carnera possessed a good chin and not the “china” chin that writers wrote about years after Primo had hung up the gloves. There was not one opponent of his that thought Carnera had a weak chin. In fact, getting stopped by the likes of Joe Louis and Max Baer was nothing to be ashamed about considering that the same fate happened to many other fighters who are presently sitting in the Hall of Fame today.

Although he lost to Louis, in his next bout, Carnera TKO’d contender Walter Neusel at 2:23 of Round 4 at Madison Square Garden on November 1, 1935 before a crowd of 12,768.

Of the Carnera-Neusel fight, the Associated Press stated, “Primo Carnera, trying for a comeback, emerged from the smoky haze of MSG with a TKO victory over Walter Neusel, the blond German heavyweight. Refusing to be floored under a barrage of ponderous, sweeping lefts, Neusel threw up his hands and quit in the fourth round after Carnera inflicted a deep cut over his eye with a massive punch. As blood spurted from the cut, Neusel’s seconds jumped into the ring with a towel, but he beat them to the draw, walking away from the grimacing Carnera to his corner. The first blow of any consequence in the initial round swept Neusel halfway across the ring and nearly through the ropes. From that first blow to the end, Carnera mussed up Neusel at will, grinning and wielding the troublesome left that had sweeping power, but not enough jolt to the deliver the knockout.”

Neusel was far from a slouch. He was a rising contender having recently scored wins over top heavyweights Tommy Loughran, Jack Peterson, King Levinsky and Ray Impelletiere, and was held to a draw against Natie Brown. Neusel would later defeat Max Schmeling.

Still on the comeback trail, in his next contest, Carnera outpointed contender Ford Smith over ten rounds at the Philadelphia Arena on November 25, 1935.

Carnera then went on to score two straight knockout wins before his skills began to erode and he lost three of his next five bouts before retiring in 1937. He did return after World War II when he was 40 and lost three fights from 1945-1946.

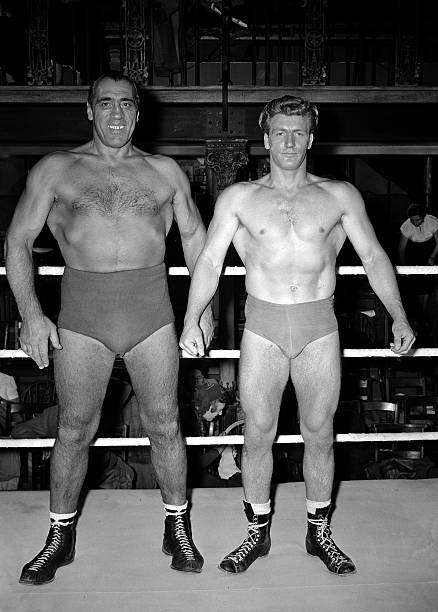

Because of his marquee name and great reputation, Carnera entered the world of professional wrestling in 1946, where he was a great drawing card and made a fortune. For nearly 15 years, Primo was one of the most popular wrestlers in the world. Since he had been a wrestler in his youth, the former heavyweight boxing champion had no difficulty in becoming a leading wrestler. Carnera went undefeated in his first 120 matches (119-0-1) before he was defeated by Yvon Robert in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on August 20, 1947 when he was 40 and Robert was 33.

On December 7, 1947, Primo defeated the legendary former World Wrestling Heavyweight title holder Ed “Strangler” Lewis. The win over Lewis earned Carnera (now 143-1-1) a shot at the reigning World Wrestling Heavyweight Champion Lou Thesz on May of 1948. Unfortunately for Carnera, at age 41, he was too old to deal with the 32 year-old Thesz and was beaten.

Besides the wrestling ring, Carnera starred in 14 movies and a TV series, owned various successful businesses, got married in 1939 to Giuseppina Kovacic, and raised two children, Joan and Umberto, who later became a doctor. Both of his children keep their dad’s name alive with the Primo Carnera Foundation.

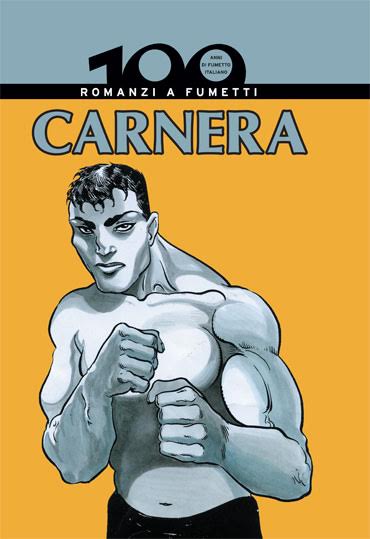

In 1947, Italy produced a comic book series “Carnera” that was popular for a few years.

That same year in 1947, a no-talent, malicious, Communist card-carrying writer named Bud Schulberg came out with a fiction book called “The Harder They Fall” that had very slight similarities to Primo Carnera, but close enough to make gullible readers believe that book was a near biography of Carnera’s career. Though the “writer” supported Communism, like all phonies he actually grew up the pampered, spoiled son of B.P. Schulburg, who ran Paramount Pictures, before he was fired for being incompetent.

Through his rich father, little Bud was rich and well-connected in the film community. While Schulberg “publicly” appeared to support the plight of the poor and common working man, there is little evidence that he donated any of his vast fortune or assistance to those he felt were beneath him, even his chauffeur was ordered to avoid the routes through the slum neighborhoods. Schulberg was such a fake, phony and fraud that he purchased his expensive tailored wardrobe from the same shop who handled the Duke of Windsor and Fred Astaire. Later when the book was turned into a film by Columbia Pictures starring Humphrey Bogart, which proved to be his last movie role, Carnera’s sterling reputation began to take a hit. Knowing this, Primo filed a $1.5 million suit against Columbia Pictures. Unfortunately, just as the same things happen today, film companies would rather spend more money on attorneys than settle cases and admit any guilt. Of course, Carnera could not outspend Columbia Pictures who, like the bullies that they were, lawyered up as if they were actually on the side of righteousness, when, in fact, they were only representing the greedy wallets of a motion picture studio, so while the case was dropped, the former champion’s reputation was forever tarnished.

All Schulberg did was take plots of mediocre B-movies and pulp fiction dime novels and insert them into the story. Though Carnera’s life had nothing to do with the story, Schulberg intentionally made the fighter a giant on purpose in order to raise similarities to Carnera.

The no-talent Schulberg was a wicked individual without a hint of decency in his despicable body. He later got credit for writing the famous “On the Waterfront” movie, although the plot was seemingly lifted from dozens of B-movies and the best lines in the film were actually improvised by someone who possessed a real wealth of talent – Marlon Brando.

While the misinformed staff of “historians” in charge of electing participants into the Boxing Hall of Fame has no problem inducting such a villainess individual such as Schulberg who never wrote a story where boxing truly looked good in, Carnera has been unjustly denied the honor he rightfully deserves, which is an appalling crime.

Fortunately, scoundrels such as Schulberg are long since forgotten, if they were ever really remembered at all, while Carnera is still a national hero in Italy and known all over the world. There are yearly festivals held in his honor and on August 31, 2008 a bronze statue of Carnera was erected at the Parco della Resistenza in Urbino, Italy.

Unlike every other publication and the Boxing Hall of Fame, this publication defiantly does not subscribe to unsubstantiated innuendos and works of fiction, but deals in truths and facts, which in today’s world of “journalism” is hard to find today.

One does not have to take our word for it, just read the newspaper accounts of Carnera’s fight’s themselves when they actually took place, or look at fight films of Carnera in action and his skills and greatness are evident.

Although the most prolific heavyweight champions of all-time were Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey and Muhammad Ali, there were still others who held the title that achieved greatness. One such title holder was Primo Carnera.

Carnera was successful all of his life and had homes in both the United States and in his beloved town of Sequals, where he went home to die on June 29, 1967 from liver disease and diabetes.

Primo Carnera was a fighter built of muscle and guts. Over the years he developed a sharp boxing style that utilized his long reach and powerful right hand, especially the uppercut. If he were around today, he would still be king of the heavyweights.

If fighters the caliber of Oliver McCall and Hasim Rahman could leave Lennox Lewis finished on the canvas, it is safe to say that Carnera would have destroyed him, along with the Klitschko Brothers, who could not take a good punch.

Carnera was a great fighter and a noble champion. To this day, he is the only native Italian to hold the undisputed World’s Heavyweight Championship. That is why in a recent poll of Italian newspapers, Primo Carnera was ranked third out of the ten most illustrious Italians of the 20th Century.

The magnitude of the great Primo Carnera’s impact has certainly not been forgotten and, although others tried to malign him, his legend still lives on through the generations.